A PILLAR OF SIX COUNTIES 1993–2004

WITH JERRY HARALSON’S departure imminent, the YMCA of Central Florida took stock of its standing in the community and its prospects for the future, as the national economy emerged from a recession of several years. Population growth in the Orlando metro area continued to astound: The Association’s service area had expanded by more than 50 percent from 1980 to 1990, to nearly 1.8 million. As immigrants continued to settle in the region, the area’s demographics were changing dramatically as well.

The YMCA had not been keeping pace with the changes. It was still running “storefront” programs in many communities where full-fledged branches were needed. Some Y programs simply operated from the back of a truck and used storage space in strip malls. Key board members at the Central Florida Association wanted to create a different kind of YMCA, but weren’t sure how to start that process.

Its existing properties were inadequate to the demands placed on them. “We had a lot of poor, tired facilities,” observed Mike Dungan, who joined the Association as Downtown Orlando branch executive in 1990. They lacked the proper space or equipment for fitness and wellness programs, or for child care activities. In short, Association facilities did not add up to a contemporary YMCA, and the organization was not following a business model.

With those properties-and the public image they created-top of mind, the Central Florida YMCA board decided to reinvent the Association. The community’s transformation in the 1970s and 1980s had drawn new businesses, residents, and tourists from all over the world. Metro Orlando’s infrastructure was stretched like never before, and new issues of concern-family, community, and quality of life-pointed to a new role the YMCA could play, in strengthening the community.

The board formed a search committee and determined to recruit a leader who could lead the change and pursue aggressive growth. They interviewed candidates and then visited the YMCAs and boards where leading candidates worked.

The committee was most impressed with the Association of Greater Charlotte (NC). This notable YMCA gave the Orlando volunteers a new perspective. From 1986 to 1993 the Charlotte Y was among the fastest growing Associations in North America, with a budget that rose from $5 million to more than $20 million. This organization had combined the YMCA mission with a business model for growth, and with newly confident volunteers propelling it, had become a significant presence in the community.

Longtime volunteer Dan Mahurin, representing the Central Florida YMCA, met the architect behind those changes, Jim Ferber. A lifelong YMCA professional, Ferber had overseen $10 million in construction at the 10-branch Charlotte Association as its district vice president. Since he arrived in 1986, he had built membership to 30,000 and energized volunteers to build a SO member Association board. Previously Ferber had led branches at another major urban YMCA, in Houston, after starting his Y career as physical and athletic director in his hometown of Akron (OH).

After seeing Charlotte and talking with volunteers there, the Central Florida YMCA search committee offered the position of president and chief executive officer to Jim Ferber. He joined the Association in Orlando in September 1993. “Jim understood what a Y could do,” Mahurin observed.

Carrying out the YMCA mission to benefit the community topped the Orlando board’s concerns. ”A lot of people on the board were very comfortable with predictability, ” recalled Stephen Miller, Association chair in 1993. “But if we stayed predictable, people weren’t going to know about us.” Now the Central Florida Association had a CEO who, with the board’s backing, could respond to the region’s new circumstances and change perceptions of this YMCA by putting it firmly on the map.

FIRST, A BOLD PLAN

FERBER WASTED LITTLE time in instigating changes. He led the Association in a major new initiative, the development of a long-range plan with goals for the year 2000 in several strategic areas. In 1994 the Metro board, other key volunteers and YMCA staff conferred in an overnight long-range planning session with a consultant Bo Hardy as facilitator and board developer. The conference energized the Central Florida YMCA and gave it new direction.

Out of that session emerged eight objectives (Key Results, p. 141). The emphasis was on developing everyone from infants to seniors, in spirit, mind and body. The plan envisioned reaching entire families, with all Y branches becoming Family Centers. Youth would remain the YMCA’s focus, especially teens and middle school students. The YMCA would also become a resource for the community. “These became our marching orders, for staff and volunteers,” recalled Ferber. “We never dreamed in 1994 how hard this was going to be or how successful the Central Florida Y would become. We dreamed about touching and impacting 200,000 lives, but we really didn’t know how we were going to accomplish the task.”

The YMCA credo “We build strong kids, strong families, strong communities” described the desires of the Association and the entire community, which was eager for the Y to lead the way. The long-range plan foresaw capital growth of $15 million to $30 million by the millennium, to serve four times as many Central Floridians – the amount necessary to involve entire family units, engaging both parents and children. With no financial resources at that time, and little confidence in the staff’s ability to manage YMCA finances, this was a daring goal for the board. The plan set forth new financing guidelines to allow the Association to take measured risks, moving it away from conservative, pay-as-you-go fiscal practices.

“We started to roll out this new vision in 1994 and 1995,” said Ferber. “The plan was difficult for people to understand and appreciate. These were great goals, but when we started to execute these plans there was some opposition from staff and volunteers alike. We didn’t realize how big the changes were going to be.”

MOVING TO A MEMBERSHIP MODEL

FERBER LED THE Association to adopt a major shift in direction, affirming that membership would become the basis of YMCA affiliation. The membership model was new to Florida, where residents had so many options for year-round outdoor recreation. But the long -term plan, with its emphasis on wellness, meant the Central Florida Y would have to abandon its programmatic approach in which people took classes of a few weeks’ duration that carried modest fees. “If we are to live up to our mission, people have to be with you a longer time,” the CEO emphasized.

The programmatic model also made finance s unpredictable. Ferber knew that returning the YMCA to its roots as a member organization would fortify the Association’s base and stabilize its finances. Annual dues would not only fund operations and foster growth, but would build long-term loyalty to the YMCA and a sense of belonging.

The plan also created a Home Mission Fund to extend YMCA work in underserved parts of the community. Until now, each branch had kept its finances independent of the others. Some volunteers preferred it that way, keeping money raised in their own locales. This parochial approach worked well for them, but it weakened the overall Association when less fortunate communities struggled to maintain their Y.

The Metro YMCA board had made a firm commitment to building up “outreach” YMCAs in diverse neighborhoods. In its new plan the more prosperous, typically suburban Family Centers would dedicate five cents of every membership dollar to sister branches in lower-income communities, thus ensuring sustainable operations. The Home Mission Fund would build reserves for Y s in financially challenged areas.

Strengthening those outreach YMCAs would achieve another important result, a better perception of the Association in the community, Ferber said: “We would truly have one YMCA in Central Florida, with one balance sheet.” The new policy took effect in 1996. Propelled by the growth in YMCA memberships, the Home Mission Fund grew to $199,000 in 1997. By 2004, the Fund stood at $1.2 million.

SUBTLE CHANGES, BIG IMPACT

FERBER, WHO HAD been in charge of marketing efforts in Charlotte, knew how much of an urban YMCAs identity derives from its buildings. They embody the organization in the community ‘s eyes. Without such strong, tangible symbols, the YMCA of Central Florida would remain the area’s best-kept secret, said John (Chip) Webb, a member of the CEO selection committee and now a real estate developer.

A survey of community leaders revealed a less than stellar perception of the Association and its facilities. Some perceived the YMCA as being “for the other guy,” Ferber recalled – people who couldn’t afford much. Others, however, saw it as a place for the affluent. The Association could not become a successful membership organization without changing those views, Ferber realized. To achieve its bold new vision for growth, the YMCA had to affect some swift and powerful changes.

To put the community on notice about its changing YMCA, Ferber began making changes at its most prominent Family Center, the Downtown Orlando YMCA adding a new two-story entrance, large windows, and a big addition to accommodate entire families. Those highly visible moves communicated a new message: “We were there to promote healthy lifestyles for the entire community,” Ferber recalled. “The facilities, programs, and equipment became the magnet.”

The four houses on Shine Street, accumulated since the 1970s, were fin ally razed to expand the Downtown wellness and child development areas. With his office in the adjacent Metro YMCA headquarters, Ferber managed the upgrade closely. The expansion and smaller improvements – new paint, tiles, carpeting, and cleaner locker rooms-had an immediate impact. “Jim raised the bar,” Dungan observed.

Following the plan’s mandate to serve the entire community, the YMCA launched an aggressive scholarship campaign for kids and families who needed financial help to participate in the Y. The increased level of fund raising for scholarships was a new way of doing business. But, said Ferber, “We acted on what we believed, that no one should be turned away because of an inability to pay for programs, services, or membership. “

In the Association’s new vision, each Family Center would become an “energy center,” deeply penetrating its three-mile radius to serve everyone. The YMCA would have enough Family Centers, with overlapping service areas, to effectively blanket the entire community. It would also offer large programs outside its walls and beyond the areas served by the Family Centers.

At this time, the Central Florida YMCA conducted its first campaign in a rural area, Ocala, where volunteers were highly motivated by the Association ‘s new vision. Since Ferber was new to his position, attorney Randy Briggs and former Florida Lieutenant Governor Jim Williams led their community in raising $2 million for the Marion County facility. “Randy was a sparkplug, young and aggressive, with a real passion for the Y and what Ocala needed,” Ferber recalled.

In early 1996, both the Downtown YMCA and its counterpart in Marion County opened their doors, introducing area residents to an entirely new kind of YMCA. Changes at the downtown fitness and wellness facility, in the heart of town, revealed to passers-by what was going on at the YMCA, as they noticed the dynamic activity within. That $1.8 million expansion served to showcase what a modern YMCA could be, as did the 38,000- square -foot facility in Ocala and the fine aquatic complex on its 18-acre site.

RECRUITING REINFORCEMENTS

AS PUBLIC AWARENESS grew and perceptions changed for the better, YMCA memberships began to increase. Campaigns in 1994 attracted 1,800 new members in January, nearly 1,500 in April, and more than 1,300 in September.

Further reinforcing the membership strategy, Ferber hired the Association’s first marketing and communications professional in 1995, “a huge step for us,” he recalled. Dori Madison left her own business to focus on building YMCA memberships, and to convince policy volunteers to place a high value on selling them. “It was not a part of their vocabulary,” observed Ferber, but he added, “it caught fire. [Membership] was a great way to engage people with the YMCA.” By 1997, membership rolls had reached 48,000, up from only 29,000 when Ferber arrived. “The emphasis on membership let the Y expand,” said Mahurin.

In another key move, in 1996 the CEO recruited Mark Russell, a seasoned professional from the YMCA of San Diego (CA) County, as the Association’s chief financial officer. Russell had the experience and expertise to develop structures needed to reach the long-term plan’s goals. “Mark was a critical piece of the puzzle,” Ferber recalled, giving the Association confidence in managing its finances and business operation.

Russell, formerly employed by the major accounting firm Coopers & Lybrand, brought skills and knowledge that the Central Florida YMCA lacked. At this time the Association, challenged just in meeting payroll and balancing its budgets, had not even considered borrowing from a bank, much less taking on debt. Russell encouraged the YMCA to consider that new direction. Before he came, the Central Florida Y maintained no programs with government. The new CFO would soon lead it in forging a significant relationship with Orange County.

Initially, Russell recalled, he resolved some urgent cash-flow problems. Working with Board Chair Chip Webb, an accountant by training, Russell created a cushion to alleviate cash crunches at Family Centers. Revenues from membership dues had begun to rise significantly, to $9.5 million in 1997, from just $4.5 million a year earlier. Each Family Center would now be required to keep three to five percent of revenues in reserve for future needs. In the first year alone, the set-aside funds earned the Association an additional $5,000 in interest income.

Bolstered by these successes in building memberships and revenues, Ferber could now more easily convince his directors to shed their longstanding fiscal conservatism and pursue Association goals more aggressively.

Its new Home Mission emphasis required the Association to equalize its facilities in diverse communities. Board member Steve Miller led the Home Mission Group in its first true outreach effort, in the Pine Hills, Bithlo, and Taft neighborhoods. In those areas the YMCA began working with local government, through Orange County’s Neighborhood Centers for Families (NCF). County Chair Linda Chapin provided the Association with NCF funds for athletics-a $140,000 commitment-as part of a countywide drug-prevention initiative.

AN AUDACIOUS CAMPAIGN

THE HIGHLY VISIBLE changes at the Downtown branch and in Marion County caught the attention of other YMCAs wanting upgrades for their facilities. But the boards of Family Centers lagged in joining the Metro board and staff in pursuing new avenues, and in adopting the Association’s changed ways of doing business, Ferber said.

Realizing that various branches had attempted but failed to accomplish expansion on their own, Ferber set out to change that dynamic. Since the Family Centers had little knowledge, capacity, or desire to raise capital dollars, Ferber convinced the Central Florida board to mount an audacious, Association-wide campaign to achieve the growth goals in its long-term plan. This centralized effort would be led by metro board directors who shared the new vision-a “build it, they will come” strategy.

This was a bold decision for the Central Florida YMCA, since it had no recent experience with capital campaigns. It had not completed an Association-wide fund-raising campaign since the mid-1960s, when it constructed Orange County’s first YMCA facilities. But if it failed to make further upgrades, the membership strategy would flounder.

Despite the remarkable growth of Metro Orlando, the area remained a tough place to raise capital funds. No large corporations were headquartered there, and Fortune 500 entities were few. The companies’ power centers, corporate leaders, and major community investments were elsewhere. Businesses in the small communities that comprised Central Florida were spread far and wide, primarily in the citrus, agriculture, ranching and farming industries.

Lacking a few strong corporations and top-level executives to set the pace, Orange County had not developed the hierarchy of charitable leadership that other large cities enjoyed. “Central Florida was a stop on the way to somewhere else in a career,” Ferber explained. Managers who wouldn’t be staying long hesitated to become involved with non-profit organizations. Nor were there families who had provided leadership to the YMCA for several generations, as in many other locales.

Nevertheless, the YMCA Renaissance Campaign went forward in fall 1996 with a $3.4 million goal. The branches slated for upgrades were the Aquatic and Family Center, Dr. P. Phillips, Pine Hills, Tangelo Park, and Winter Park. The choice of those Family Centers was very strategic. “We knew we were only as strong as our weakest link,” Ferber recalled. As well, the overall mix made a great case statement for funders, Y members, and communities. The Tangelo Park and Pine Hills Y s were small operations in disadvantaged neighborhoods and didn’t meet minimum YMCA standards. Some thought had been given to moving the Tangelo Park Y out of the isolated African-American community of less than 1,000 homes, where few residents could afford a Y membership, not to mention capital contributions.

By contrast, the Winter Park and the Dr. P. Phillips Ys were located in affluent communities that could afford to contribute for capital improvements. The Winter Park branch, opened in 1968, was outmoded and offered little beyond aerobics, basketball and weight-lifting. It was a typical older YMCA, with a budget of about $800,000 in 1996. Moreover, Ferber added, “The local commissioners accused us of not being a good corporate citizen, of not serving the community.” Winter Park had to become a place for the community to gather, connect, and develop relationships, a place for the entire family.

The rundown Aquatic and Family Center had been operated by the adjoining hotel as an event-oriented community resource. By 1994 it risked closure by its insurer, due to safety and risk management issues. “We needed to make improvements and add a membership component,” Ferber recalled.

The capital campaign would raise funds for all five Ys. Dan Mahurin, the veteran YMCA fund-raiser whose term as Metro Board chair had just ended, was tapped to chair the Renaissance drive. Mahurin worked at SunTrust in Orlando, but later moved to Tampa as the bank’s chairman and CEO. Charles (Chas) Bailes III, who had recently joined the Association board, took over as the drive’s second chair. A Central Florida native, Bailes grew up in Tampa and returned to Orlando in 1978 to head his family firm, ABC Fine Wine and Spirits.

The two leaders, who enjoyed considerable influence in the business community, enlisted other key volunteers to team up and extend the campaign’s reach (Keystone Leaders, below). This powerful team solicited widely in Orange County communities, enlisting both individual and corporate support.

The team’s first step was to canvass “family” – board and staff members throughout the Association. They raised more than $200,000 in board contributions and in excess of $100,000 from staff. Then the leaders began calling on businesses. Early on they contacted the Darden Foundation, linked to Darden Restaurants where YMCA Director Clarence Otis Jr. served as corporate treasurer. At that time, the Association’s largest single gift had been $100,000. The Darden request brought an unheard-of $500,000 donation.

“What excitement!” recalled Ferber. “It changed the mindset of the YMCA leadership and brought the team together. We gained a new sense of energy.” Based on their coup with Darden, the leaders raised the Renaissance campaign goal to $5 million.

AN EARLY OUTREACH SUCCESS

FUND RAISING GAINED further momentum when Harris Rosen, an advocate for the Tangelo Park neighborhood, agreed to assist with the $1 million campaign goal for the YMCA there. Although Renaissance proceeds went into a general fund, individuals could designate gifts for specific Family Centers. The small facility, near Rosen’s hotel headquarters, was one of the most at risk in the YMCA constellation.

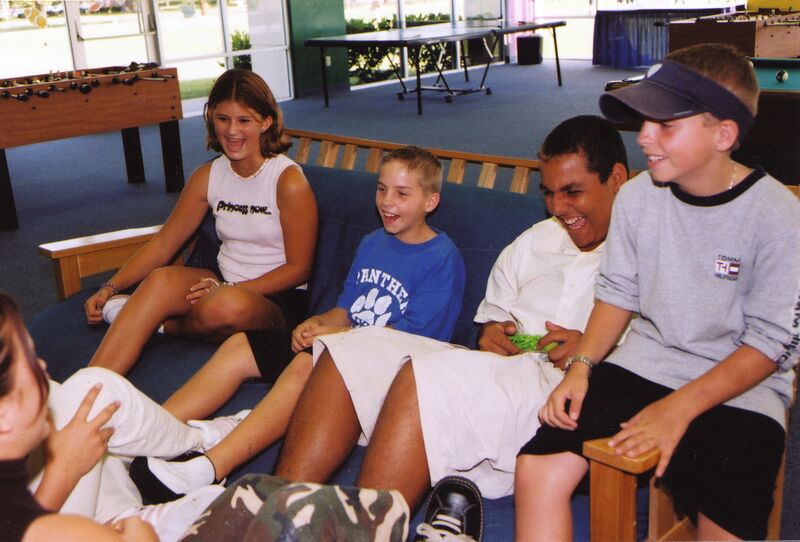

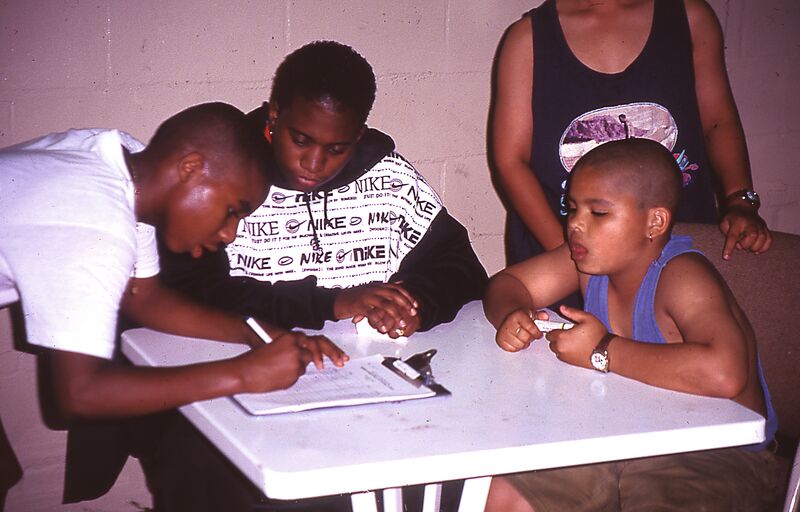

The Orange County school system had created an alternative program for high school dropouts, and asked the YMCA for use of its Tangelo Park and downtown facilities as sites for 20 teens each. They offered an ideal non-academic setting, where recreation and mentoring could take place. Rosen supported the Tangelo Park Pilot Program, in which agencies like the YMCA collaborated to improve residents’ lives.

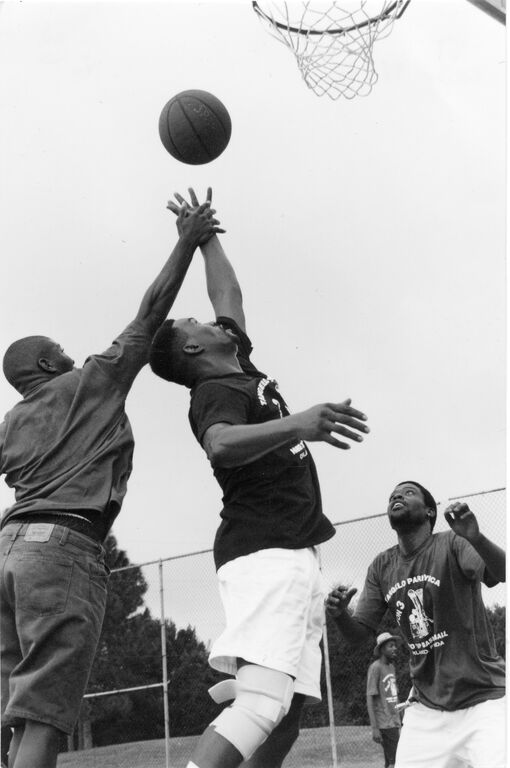

The hotelier made a personal gift of $100,000 to the Tangelo Park Y-still a considerable sum at that time for the Central Florida Association. Moreover, Rosen’s donation and endorsement lent great credibility to the branch. The Pepsi-Cola Company followed with a $50,000 donation. John Gabriel, a YMCA board member and then general manager of the Orlando Magic, and the foundation named for Anfernee (Penny) Hardaway, an All-Star guard on the team, contributed another $50,000 to fund an indoor basketball court for youth.

The Magic gift, coming the last week of December 1996, carried special significance. Without it, the YMCA would have had to forfeit a two-for-one match, with a year-end deadline, from the Heart of Florida United Way. That sum, $208,000 from the community capital fund, made the construction possible at Tangelo Park.

In 1997, the small branch unveiled its new Harris Rosen Family Life Center and Penny Hardaway Gymnasium as a safe haven for kids. This renewed Y facility went far in changing public perception of the Central Florida YMCA in the larger community. What transpired in that neglected neighborhood had a profound impact on the YMCA movement in Central Florida.

SUPPORT STARTS TO SNOWBALL

THE EARLY SUCCESS at Tangelo Park, coupled with the Darden gift, built considerable confidence in YMCA volunteers and staff. The YMCA badly needed every dollar, but also had to show the community that it was an organization worthy of their investments. The stunning results at Tangelo Park did just that, proving that the YMCA could prevail even in one of the most disadvantaged communities.

Like Tangelo Park, the Pine Hills YMCA had been a program center until 1993. But in the new vision of the Central Florida YMCA, the Pine Hills Family Center could become a safe, secure place for people to gather and forge positive relationships. The very diverse, financially troubled west Orlando neighborhood had few businesses and far too many drug peddlers. “When the police broke up drug deals, they came right back,” Ferber said.

In 1996, the Central Florida YMCA obtained a larger building on 15 acres that once housed the Walsie L. Ward Girls Club, with $1 million from one of The Dr. Phillips Charities. But the Pine Hills Y required more financial support than the local community could provide to add a gym, wellness programs, and child development activities. Pine Hills Family Center board members Jon Dunwell, pastor of Westwood CMA Church; Tim Haberkamp, a local business owner; and Mont Thurston, a Sun Trust branch manager, were on the Renaissance campaign team.

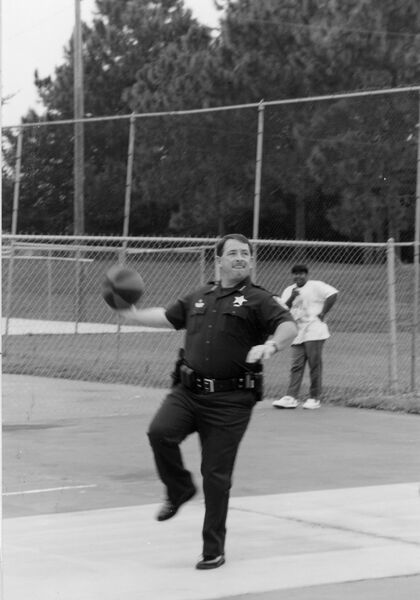

The Orange County sheriff had been a supporter of the Pine Hills Y, allocating drug prevention funds to the branch, and several commissioners, including Mable Butler, had given discretionary funding. Emboldened by that show of support, Ferber arranged a Christmas Eve campaign call with Sheriff Kevin Beary and Pastor Dunwell to ask Leonard Williams, president of the Wayne M. Densch Charities Inc., to help strengthen the Pine Hills Family Center. “He knew that local kids needed a place to go,” Ferber said.

Williams promised a surprising $600,000 gift from the Wayne M. Densch foundation. It was the Association’s largest gift to date. “I came home very happy,” Ferber recalled. The Pine Hills branch would become the Wayne Densch YMCA Family Center in 1999, and Pastor Dunwell and Sheriff Beary continued to be avid and active supporters of the YMCA. The Darden Foundation contributed as well, and the branch gymnasium bears its name.

For the Aquatic and Family Center, the Association turned to Florida Hospital, a Seventh-day Adventist institution. The state’s largest hospital agreed to provide $900,000 for a YMCA wellness facility that would also be a rehabilitation site for orthopedic, cardiac, and pulmonary patients. The hospital regarded the YMCA as a more beneficial environment for its rehab patients, who performed better in lively, energetic settings.

When the Renaissance drive concluded in 1998, after two whirlwind years, it had amassed $10.2 million-a resounding vote of confidence for the Central Florida YMCA and what it could offer the area’s diverse communities. Succeeding beyond anyone’s imagination, the Association had nearly tripled its initial, modest campaign goal of $3.4 million.

During the campaign, which focused on existing facilities, two very compelling projects were taking shape in Orlando, unforeseen at the start of the drive. Association leaders became aware of two opportunities, at Jay Blanchard Park and Lake Nona, which held a world of promise. These areas, in the eastern part of Orlando, had been identified as prime targets for service in the Association’s long-range plan.

Orange County was planning to upgrade Blanchard Park, and a new community was envisioned at Lake Nona. Both entities, observing the YMCA’s astonishing growth, expressed interest in YMCA participation. “The buzz in the community became, ‘How do you partner with the Y?” Ferber recalled. Emboldened by its successful hospital partnerships and strong relationships with county officials, the Association entered into serious negotiations. The results would signal a major strategic shift for the Central Florida Y, into public/private partnerships.

The Association had gained momentum as never before. “We learned a great deal from the Renaissance Capital Campaign,” Ferber said. “It took place during a time when the Central Florida YMCA was at a crossroads. The fact that we chose to go forward with the campaign changed the history of this YMCA-forever.” Harris Rosen summed it up succinctly: “Jim Ferber guided the Y to the very top in the community,” he said. “It gained a tremendous amount of credibility.”

PUTTING PROCEEDS TO WORK

WITH THE RENAISSANCE funds in hand, the Association began its most ambitious expansion ever, undertaking projects simultaneously. Pine Hills soon began renovations on its 18,000-square-foot building. The Dr. P. Phillips YMCA gained a 4.5-acre soccer field, with targeted support from one of The Dr. Phillips Charities.

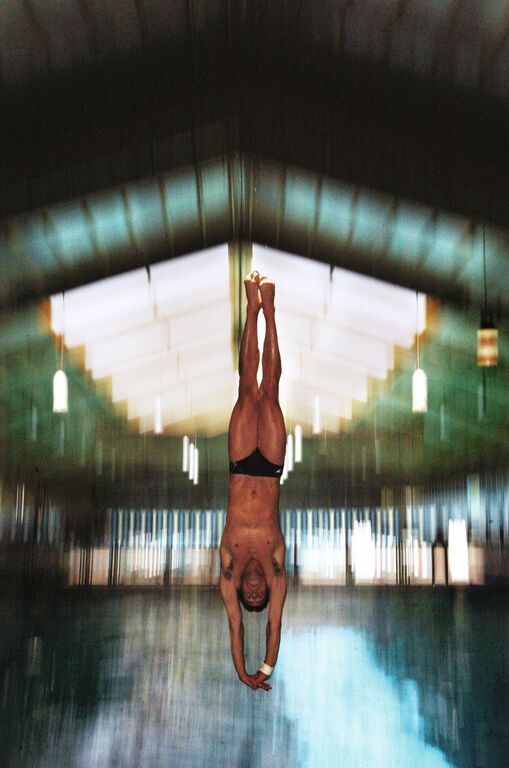

With funding from Florida Hospital, the Aquatic and Family Center built a 5,500-square-foot wellness area for YMCA members and physical therapy patients. This partnership signaled a turnaround for the formerly struggling Center, which soon became a vibrant membership organization. That first year, the branch hosted the YMCA of the USA Swim Meet and 25 other national events.

The $2.5 million Winter Park expansion on Lakemont Avenue, led by local volunteers Diane Thornton and Mary Rumberger, was a complete renovation. By adding a wellness center, a child-watch area, and youth recreation room, the branch became a true Family Center. Its Eastbrook Center was also refurbished inside and out, and five acres were added to its site. Following efforts of Winter Park’s Membership Director Star Vasbinder, its rolls topped 9,000, and this YMCA gained a prominent position in its community.

Success bred success. The Central Florida YMCA also began ambitious changes at Family Centers apart from the Renaissance Campaign. The Golden Triangle YMCA site was doubled, to 30 acres, with an eye to future growth as a major Family Center. The Seminole County YMCA Family Center expanded its Lake Mary property with an exercise room, full workout room, and a large program area for summer and holiday camps, after-school sports, and midnight basketball. Its large swimming pool answered a com- where there were few public pools. The Sanford Herald deemed the revamped Seminole Y one of the county’s hidden treasures. It would expand again in 1999.

The South Orlando YMCA Family Center acquired more than $40,000 of wellness equipment, and opened a child development center with Orange County. The West Orange YMCA renovated its gymnasium and child watch area, and installed $50,000 in equipment in its wellness area. Maintenance, repairs, and upgrading continued at Camp Wewa, the Association’s oldest property. But these expansions were larger than the sum of their parts they changed the face, and the culture, of the Central Florida to take risks, as they saw the difference their “new” YMCA was making in so many communities – and in people’s lives. “For the first time, we were working on a long-term strategy, not just thinking about today,” Ferber said. “We wanted the YMCA to be a place where people could leave a legacy.”

The Renaissance drive—the first concerted, Association-wide fundraising since the 1960s—had both visible and subtle effects, within the YMCA and the community at large. The Central Florida Association had started down a new path, developing important relationships and trust. Building on tangible evidence SunTrust Bank to back a 15-year tax-exempt bond for $11.25 million, at less than five percent interest. Russell engineered the complex offering in November 199 7, which required approvals from commissioners in Orange, Seminole, and Marion counties. Public hearings were held on economic impact.

A PATH-BREAKING PARTNERSHIP

IN THE 1994 long-term plan, the Association identified the eastern section of Orlando as a prime area for a new YMCA. The Central Florida Y had offered programs in this part of town for some time through its Eastside extension, which hosted summer camps in Blanchard Park. Eastside’s parent-child, day-camping, after-school, and youth sports programs always drew large enrollments, clearly demonstrating the need for a YMCA in eastern Orange County.

The formerly rural area was sprouting new homes, but had little sense of community. It lacked a center for neighbors to meet, a site where children, families, and seniors could come together. It needed a safe gathering place for teens. The YMCA’s mission, vision, and values could help to fill those gaps.

The 84-acre Jay Blanchard Park in northeast Orlando offered great potential. There, Orange County was building an eight-foot-wide pathway linking the city and the nearby University of Central Florida. The five-mile trail, paralleling the Little Econlockhatchee River, would be ideal for biking, hiking, walking and rollerblading. The County also planned to build a structure of 10,000-12,000 square feet at the trailhead, for shelter and restrooms, but “it was pretty plain,” Ferber recalled.

Building on relationships with Linda Chapin, Orange County chair, and Larry Jones, County Health and Family Services director, Ferber initiated a discussion about adding a YMCA facility there. The officials reacted with interest. Soon several leaders from government and the YMCA, including Chapin, Jones, Steve Miller, Tim Eves, Bill Starmer, and Dave McCumber, began discussing the idea of a partnership. In turn, the East Side board, the YMCA staff, and others on the Metro board and Executive Committee joined the effort.

Metro board Chair Steve Miller became the key leader on the project. He was “the right person at the right time,” recalled Ferber, given his years of experience in working with government entities, staff, and politicians, and his commitment to the YMCA mission and values.

The County Parks and Recreation Department convened citizens’ committees to consider the possible collaboration. During one YMCA presentation, a county staff member asked if the word “Christian” could be removed from the presentation. Without hesitation, Miller replied “no.” As Ferber recalled, “It would have been a deal-breaker if they had insisted on our removing ‘Christian’.”

Some environmentalists and residents opposed not only adding a YMCA but building anything at all in a county park. Eastside YMCA supporters effectively countered their arguments. County Commissioner Mary Johnson, who was eager to see a full recreation facility there, gave the Y plan her support. Eventually the partnership prevailed, and the city and county donated $1.9 million to fund the $4.2 million YMCA project. The county would own and lease the land and property to the Association for 30 years, at $1 a year.

The negotiations, led by YMCA board member and attorney Thomas Warlick, lasted a year before achieving a contract. The County changed its negotiating team three times. “Tom did an incredible job,” Ferber observed.

In March 2000, the 27,000-square-foot Blanchard Park YMCA Family Center made its debut. The Y sits at the trailhead, and remains open when the park closes at 6 p.m. Although the Family Center charges annual membership dues, the facility is open and free to the community on Friday evenings. Like other Y branches, Blanchard Park awards scholarships to people in need of financial assistance so they can join. This Family Center is governed by a board of managers and an oversight committee of county and YMCA representatives.

This unusual project also had a larger effect, both on the Association and on Central Florida. The YMCA team of staff and volunteers was growing stronger as it forged ahead with a common dream and vision. The growing confidence had a spillover effect on the community at large, as it observed the Association’s astonishing growth and success.

ANCHORING A NEW COMMUNITY

THE LAKE NONA project began in meetings of an Education Task Force named by Orlando Mayor and former YMCA camper Glenda Hood. The 20-member task force included Jim Ferber, Steve Miller and real estate developer Randy Lyon. These men found they shared a similar dream.

“There was much conversation about what made some schools so successful and why some struggled,” Ferber recalled. “It takes many ingredients to build a great school-teachers who care, enough resources, a good physical environment, involved parents, internal and external support, curriculum, creativity, the arts, physical education, up-to-date technology, good attendance, and consistency-students and teachers staying together for an entire year. Education has to be fun, so that students want to be there.”

Lyon was creating a planned community at Lake Nona, east of the Orlando International Airport. The area’s phenomenal population growth spurred continuing demand for new housing, but it lacked essential amenities for residents. Lyon was eager for a public school there, one that would enjoy a high degree of parent involvement. Through his contacts with the YMCA men on the Education Task Force, the idea of a school, park, and YMCA began to emerge.

The situation posed risks for the Association; the area was just “gators and swamps, with no one living there yet,” said Ferber. The YMCA would be going in on faith, not knowing who would use its services. “It was the first time we’ve ever been in front of the growth,” the CEO added, in a community without anchoring schools or other institutions. The City of Orlando ‘s support for the large tract of land it had annexed gave the Association confidence, however, since it was investing solidly in vital infrastructure such as roads and sewers.

The YMCA Metro Board agreed to become one of the project’s anchors by creating a Family Center at Lake Nona in a shared structure. The Lake Nona YMCA would use one side of the building and the Northlake Park Community School the other, with a common entrance. The dual-purpose structure would be situated in a 35-acre municipal park. It was an ingenious use of space, since separate entities would have required 65 acres.

An unprecedented five organizations came together in the $12.5 million Lake Nona capital partnership: The Orange County Public Schools, the City of Orlando, the Lake Nona Development, Orlando Regional Healthcare Systems, and the Central Florida Association. Mayor Hood skillfully steered partners through intricate negotiations, and Tom Warlick, again chairing the YMCA board, acted as the Association’s attorney. The partnership is symbolized by a seven-foot column at the school-and-YMCA building entrance. Each partner is represented by a word: “know ledge” for the Schools, “health” for the Healthcare Systems, “community” for the City, “vision” for the developer, and “faith” for the YMCA.

The Lake Nona YMCA Family Center, opened in 1999, was funded by the Association, with $ 2 million; the school system, at $8.5 million, and the city of Orlando, with $2 million. The YMCA and the school form the community hub, remaining open from 6 a.m. to 9 p.m. daily. The Y membership desk is just inside the entrance, and the YMC.Ns recreation center and swimming pool are used by one and all. It is Orlando’s only public elementary school with a pool. Students, 70 teachers, and 50 YMCA staff members occupy the building; no walls separate the “Y’ and the school. The Ys extended-day program carries on after teachers dismiss their last classes.

The Lake Nona YMCA set a national precedent. As the only Y in the United States to share facilities with an elementary school-everything from the lobby, classrooms, ball and soccer fields, music and art rooms, multi-media center, computers, cafeteria, office and even phones-it has become a magnet for visitors from every state and many other countries. This model partnership won an international award in 2000 from the Urban Land Institute, for best use of land and resources, in recognition of the joint efforts of city, schools, and the YMCA that conserved many acres of land.

FORGING THE PARTNERSHIP MODEL

THE BLANCHARD PARK and Lake Nona partnerships were the most complex the YMCA had attempted, Ferber emphasized; each required lengthy legal work. With several partners at the negotiation table, reaching agreement on terms and contracts was an arduous process that spanned many months.

Warlick acted as the Association’s attorney and chief negotiator on both projects. This metro board stalwart had a true passion for the YMCA and its work. “Tom is the heart and soul of the Central Florida YMCA,” observed Ferber. “It was hard for other lawyers to negotiate with him, because he was negotiating from his heart.” Ferber estimated that Warlick has provided more than $1 million in pro bono legal services to the Central Florida YMCA over the past two decades.

With Warlick, Ferber, and Russell as its key negotiators, the Metro Board had confidence because its team” was in charge, Ferber recalled. The men became known as hard-nosed negotiators who protected the YMCA’s best interests in forging the partnerships.

The innovative Blanchard Park and Lake Nona ventures established a model for future YMCA partnerships in public parks. In late 2004, the Association offered land it owned adjacent to the South Orlando YMCA Family Center to Orange County for a pocket park. The Y would lease the land to the county, and local residents and YMCA members alike could use the park. The county would maintain it and construct an outdoor basketball court, a skating area, and other sports fields there.

As the Central Florida Association joined in public-private partnerships it was inventing an entirely new way of doing business in the YMCA. Moreover, those out-of-the-box partnerships elevated the Central Florida Y to the ranks of the fastest-growing urban YMCAs in the United States, and showed its counterpart urban Associations an entirely new way of doing business while putting the YMCA mission into practice.

SERVING NEW POPULATIONS

CENTRAL FLORIDA’S LONGSTANDING African-American community had been augmented in the 1980s and 1990s by heightened immigration from Haiti, Jamaica, and other Caribbean Basin countries. The Latino population had grown and changed, evolving from a formerly dominant Puerto Rican base to include Central American and Caribbean Hispanic residents.

In 2000, black and Latino residents each accounted for 12 percent of Central Florida’s population. But by 2003 the U.S. Census Bureau reported that nearly 95,000 more Hispanic people had settled in the area, for a population of 464,000. Hispanics now accounted for 14 percent of the region’s 3.28 million residents.

The Association’s Black Achievers initiative had gained great awareness in the community, positioning the YMCA as an organization for everyone-in economically challenged as well as affluent areas. With high school graduation rates in the YMCA’s six-county area unacceptably low, the Achievers program focused on helping minority students to graduate. The program drew on its roster of Adult Achievers, chosen from African-American business and professional leaders, to help teens set personal goals, share in the adults’ professional lives and understand how they built their careers, all of which broadened students’ horizons.

“This is a win-win situation,” Ferber said of the Achievers program. “Kids win, the volunteers feel great, and schools see more positive graduation rates.”

Black Achievers expanded to the Marion County, Tangelo Park, and West Orange Family Centers. After-school enrichment and academic support programs were added at the Callahan Neighborhood Center, Richmond Heights Elementary School, and MTOMBA!! Village at Eccleston Elementary School. (MTOMBA!! is a term in elementary and middle-school Achiever programs that signifies “More Than One Month Black Achievers.”) The Achievers program explored and celebrated African-American accomplishments year-round, not just during the national Black History Month.

In 1999, the Association introduced a new YMCA Achievers Program, called Developing Hispanic Leaders (DHL). This program started in predominantly Latino South Orlando, building on the success of Black Achievers. Like its older sibling, YMCA Achievers Program-Developing Hispanic Leaders is a youth mentoring and enrichment program in which adults coach teens to be successful in life, work, college and careers. The program aims especially to reduce the high drop-out rate among Latino male students. DHL was then introduced in other parts of Orange and Marion counties.

In DHL programs, young Hispanic leaders typically meet after school and on Saturdays, when most parents are working and they have little to do. In 2001, DHL added a summer entrepreneur program in Apopka for 40 middle school students. The program has “absolutely helped the kids,” said Sentinel journalist Myriam Marquez, a former Adult Achiever, who assisted young people with skills such as opening bank accounts and preparing for exams.

CELEBRATING CHRISTIAN ROOTS

IN THE 1990s many YMCAs were moving away from an overtly Christian emphasis, especially in urban areas whose populations were ethnically, culturally, and religiously diverse. This engendered much discussion and some consternation among leaders in the YMCA movement who saw its Christian heritage as the Association’s raison d’etre.

Nationally, the YMCAs spiritual emphasis had been evolving to character development. Character-building had long been important to the Association, but now it became more explicit. The YMCA of the USA had agreed on four “core values” -caring, honesty, respect and responsibility, -that could be claimed and shared by people of any religious belief, or those who professed none. A number of Associations added “faith” as a fifth value, among them the Central Florida YMCA.

Jim Ferber was eager to renew the Association’s emphasis on its Christian roots. “Previously, it was sporadic,” Mahurin observed. Prayer meetings are not uncommon at Central Florida YMCA Family Centers or before athletic games. Christian Emphasis or Mission committees determine the extent of religious activities at branches. Dungan and others started a prayer meeting at the Downtown Orlando YMCA chapel in the early 1990s, and now 10 churches hold Sunday services at various Family Centers. Some branches maintain active chapels, like Winter Park, whose Lakemont Avenue retreat-room door bears the inscription, “Jesus: He’s Why We’re Here!”

As part of the long-term plan, Ferber saw an opportunity for the Association to extend its mission in spiritual outreach -” to highlight the ‘C’ in YMCA,” he said. He felt the Association’s Christian emphasis wasn’t visible enough. In 1995, the Central Florida Association began to host an annual community-wide Celebration of Prayer, with Florida Hospital as the sponsor. Some 800 people attended the first gathering, during Holy Week. The speaker was Leighton Ford, a brother-in-law of evangelist Billy Graham. It was a huge success, helping to put the YMCA on the map, Ferber observed. The breakfast continues to draw well known speakers (see Appendix A, p. 184) and 1,000 to 1,200 attendees each year.

At the 2004 Celebration of Prayer in Orlando’s First Baptist Church, Ferber called the event “a unique opportunity to celebrate the YMCA’s Christian heritage and mission that has guided our organization through 60 years of community service and leadership… [it] supports our mission to connect individuals, families, and communities with opportunities based on Christian values that strengthen Spirit, Mind, and Body.”

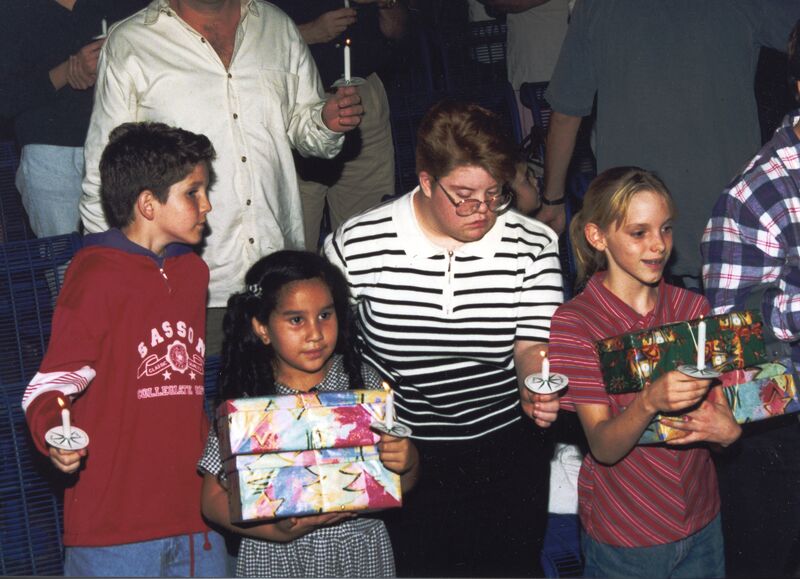

The Association also expressed those values through social service. In 199 5, the Central Florida YMCA initiated the annual Operation Christmas Child, which collects items of clothing, toothbrushes, coloring books and crayons, small toys, candies and other items, putting them in shoeboxes with a note from the contributing family for children in need. In its first year, the organization processed 80,000 shoeboxes at its Family Centers, destined for youth in troubled areas like Bosnia, Croatia, and Rwanda. One Orlando family, as a result of correspondence with their “Christmas Child,” adopted a Bosnian girl. “Shoeboxes can change the world,” said Ferber.

Some 85 volunteers from metro and Family Center boards met in August 2000 to set goals and review the Central Florida YMCA mission statement. As Tommy Hicks, a former chair of the long-range planning committee, once told fellow volunteers, ”Although the first thing one recognizes in the YMCA name is that we are a Christian organization, we must remember to maintain that our doors are open to everyone regardless of individual beliefs.” Central Florida’s mission was carefully restated, as in previous years, to allow for a Christian emphasis and expression of values while welcoming all people to its programs and facilities, no matter what their traditions or persuasions. (Central Florida YMCA Mission, 2000, p. 159.)

The city of Orlando sponsored an annual breakfast, started by the Southwest Orlando Jaycees, to honor Arthur R. (Poppy) Kennedy, a local leader who was the first president of the Negro Chamber of Commerce in 1945, and Orlando’s first African-American elected official when he joined its city council in 1972. Due to his strong beliefs in education and hard work, Pappy Kennedy provided a powerful example in a community seeking racial unification and strong role models. The city included it as part of its celebration of the spiritual and civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King.

Attendance was declining; only about 400 people attended in 2000. Mayor Hood asked the Association to step in.

The YMCA agreed, after it became the sponsor, the Celebration of Prayer breakfast grew to an attendance of 650 people in 2004.

In an interview that year, Ferber explained how he sees the YMCA’s place in what he considers the seven major facets of life: spiritual, health, recreation, civic, self-development, family, and work. While most people experience those aspects, “they ‘re not always in balance,” he observed. ”As you go through life, the emphasis shifts. The YMCA can play a tremendous role in people ‘s development, helping with all those aspects.”

SIGNAL CHANGES

FERBER REALIZED HE needed a strong right hand to run the sprawling operations. He turned to Dan Wilcox, a colleague since 1980 when both men worked at the Downtown Houston YMCA. After Ferber moved to the Charlotte Association, he had recruited Wilcox to operate its Central branch. “Both Charlotte and Houston boomed with success,” Ferber recalled.

Once in Central Florida, Ferber again asked Wilcox to join his team, as vice president of operations and membership. It was not an easy sell, since Wilcox was well settled in Charlotte. But after a trip to Orlando and subsequent phone calls, Wilcox was persuaded that a potentially rewarding challenge awaited him at the Central Florida Y. He joined the staff in 1998 and quickly became instrumental in this YMCA’s bold endeavors.

The Central Florida YMCA’s image and awareness had reached a new pinnacle by the late 1990s, with stronger Family Centers in numerous, diverse neighbor hoods and community-wide programs like YMCA Black Achievers, Developing Hispanic Leaders and the prayer breakfasts.

The year 1999 was a pivotal one for the Association. Encouraged by the unprecedented partnerships it had forged at Lake Nona and Blanchard Park, the YMCA continued to seek alliances with public entities and hospitals. Partnering opened up new ways to serve the community and gave the Central Florida YMCA a bold new direction for the coming millennium.

“We had to develop new ideas to grow and expand our mission and vision,” Ferber recalled. “The traditional way of raising dollars was not going to work.” In other urban areas, that tradition relies on a considerable core of people and families who had historically been involved with the YMCA, and locally based corporations that are reliable supporters.

That year the Association forged a partnership with the Winter Park Health Foundation, through its president, Patricia Maddox, when Winter Park Hospital was sold. The Foundation’s two properties- the 1992 Peggy and Philip B. Crosby Wellness Center on Mizell Avenue, and a 1998 structure on Red Bug Lake Road in Oviedo – would become part of YMCA operations on a long-term lease, while the Foundation retained ownership of the $ 10 million facilities. Each building comprised 40 ,000 square feet. The former Eastside branch, moving into its new home in Oviedo, became the Center for Health and Wellness.

Also in 1999, Clarence Otis was elected chairman of the Central Florida YMCA, the first African American ever to assume this key leadership role. In that critical last year of the 20th Century, his assuming the helm carried enormous impact and significance in a historically segregated city and Association.

When Wilcox was promoted to chief operating officer in 2001, Ferber completed a triumvirate that also included CFO Mark Russell. This three-man team brought energy, excitement, and enthusiasm to the work, combining the best business practices with a firmly mission-driven model. As Wilcox freed Ferber up from day-to-day operational issues, the CEO could focus more intensively on the big picture, pursuing the creative ideas that were transforming the Central Florida YMCA into such a dynamic Association.

EMBRACING THE SPACE COAST

IN 2000, THE YMCA in coastal Brevard County asked to join the Central Florida Association. Although the county had more than 500,000 inhabitants in an area dominated by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the Kennedy Space Center, its YMCA offered few services.

The Brevard County Y, which had struggled financially over the years, consisted primarily of a storefront operation in Melbourne that went out of business, and an outmoded operation in Titusville with sub-standard programs. Public perception of the YMCA in Brevard was not positive. The YMCA operations needed a major overhaul, and its services were needed in other parts of Brevard County as well.

This YMCA had one significant asset: a small group of volunteers with a contagious commitment to the YMCA mission and values. State Farm Insurance agent Robin Fisher, a Y volunteer leader for 15 years, successfully led a $1.5 million capital drive for the Brevard YMCA. But despite those results, a shortage of operating money and expertise led the volunteers to turn to the Central Florida YMCA for help. The Association was ready and willing.

Fisher initiated talks with the Association about a possible merger, a somewhat unusual step since smaller YMCAs typically avoid forging relationships with larger entities like the Central Florida Y. Many prefer to remain independent, even if struggling, and others decide to break away from larger associations.

The resulting merger of the Brevard County YMCA and the Association was a major one, and offered new opportunities for both. The Association added capital dollars to those raised by the Brevard County Y, which was renamed the Titusville YMCA. That facility got a $2.85 million overhaul that included a new swimming complex. In 2001, the Central Florida YMCA expanded its presence in Brevard County when it gained Wuesthoff Hospital’s Rockledge and Suntree Wellness Centers. They became the Wuesthoff Fitness-Plus Rockledge and Wuesthoff Fitness-Plus Suntree YMCA Family Centers. With its new branch in Brevard County, the growing Association once again spanned six counties.

The YMCA’s success in Brevard County paved the way for another pioneering partnership, this time with Brevard Community College in Cocoa. The college could not maintain its swimming pool and gymnasium, but both the campus and the local community had a great need for recreational facilities and wellness programs.

There was little precedent for a full-fledged YMCA to be located on a community college campus. Yet, the Central Florida Association was the logical partner to adapt the 38,000-square foot facility, including a 50-meter outdoor pool, into a comprehensive YMCA operation. In April 2004, the Association launched its Cocoa YMCA Family Center at Brevard Community College. The branch would serve local residents as well as college students, faculty, and staff. When it opened, the Rockledge Family Center closed and relocated to the new facility in Cocoa.

Shortly thereafter, Robin Fisher was elected to chair the metro board of the Central Florida Association. He thus became the first YMCA chair ever from Brevard County – and the first to have no direct ties, business or residential, to Orange County.

REVIVING OLDER YMCAS

OLDER FACILITIES IN the Association, like Titusville’s, had been greatly in need of expansion or rejuvenation. In particular, the small Osceola County YMCA Family Center in Kissimmee had strived to serve its community for nearly three decades with little local support. Losing up to $150,000 annually for 12 consecutive years, it had necessarily cut back on programs. During that time, the county had changed significantly, transforming itself into a bedroom community for lower-income workers at the Walt Disney World Resort. The former cowboy and ranching center was increasingly populated by Latino immigrants who worked in nearby entertainment and service businesses. The new Buenaventura Lakes and Poinciana developments provided housing for thousands of residents.

In the late 1990s, the Osceola County YMCA Family Center board obtained property from the adjacent airport to construct a YMCA facility, and called on national Y consultants for advice. Based on the plan the consultants developed, the branch pursued a promising government-funded program. Family Center Board Chair Marta Hertzog, of the Osceola Council on Aging, helped this Y secure a grant from the state’s Department of Juvenile Justice. The branch would offer after-school activities for youth with poor school attendance and academic performance who attended alternative schools and typically went home to empty houses. Now their school bus would drop off those who chose the optional Bridges program at the Osceola County YMCA.

The grant-funded program, coupled with branch cost-cutting efforts, produced a balanced budget at the Osceola County Y over the next three years. Its improved finances helped to restore community confidence in the YMCA, recalled Mike Dungan, then its executive director. But during this time the parent of a young swim team member, Osceola County Commissioner Mary Jane Arrington, became distressed by the rundown facility and grew impatient with the Association. She asked for a formal meeting with Jim Ferber.

Arrington told Ferber frankly that she and her fellow commissioners saw no hope or vision at the branch in Kissimmee. The discussion did not proceed smoothly, Ferber recalled vividly. “Mary Jane gave us a history lesson,” he said. “She took me to task-did I know what a real YMCA looked like?”

However, the officials wanted a better YMCA in their community, and were willing to help bring it about. Arrington’s parting line to Ferber was an about-face; while she was disappointed, she said she was “willing to help.” She asked Ferber to put together a bold proposal to the Osceola County Commission.

Arrington didn’t indicate how much funding might be available, and the YMCA had no guidelines. Nevertheless, the Association assembled a $1 million plan for a completely new facility, including a wellness center and swimming pool, on the existing site. There was some talk of changing its location, but the commissioners urged the YMCA not to spend money on land. The county commission swiftly approved the Association’s plan, and offered a $1 million matching gift to make the facility a true community center. Together, they would remake the Osceola Y into a great YMCA Family Center.

The YMCA soon mounted a community fund drive, led by Barney Veal, Linda Guttermuth, and Brian Marks. Dungan solicited assistance from the town of Kissimmee through the Rotary, and the city manager responded positively. As a floor hockey player at this Family Center, he had a personal stake. “He held the key and would open the city door,” said Dungan.

The municipality was under pressure to build a second swimming pool. In a cost-saving move, it crafted an agreement with the YMCA to let Kissimmee residents swim there for the same fee the municipal pool charged. By avoiding those construction costs, the city was able to give the branch a $500,000 matching gift. The Osceola County public schools, also in need of a competitive pool for swim teams, donated $400,000 to the effort. In turn the YMCA offered all first graders free swimming lessons, and gave school teams the use of its pool for swim meets.

Within a year, $1.1 million was raised in the community. Walt Disney World, the area’s major employer, donated $200,000 through its president, Al Weiss, to support both the YMCA and the area that housed so many Disney employees (one-third of the entertainment complex is in Osceola County). The Edythe Bush Charitable Foundation and one of The Dr. Phillips Charities made major gifts to restore this YMCA, and local businesses also pitched in.

The $3 million Osceola County Y, reopened in 2002, has succeeded as a young, family-oriented branch in a community of primarily starter homes. Membership rolls jumped to 4,000 from 400, even before the rebuilding effort began.

The branch that began in Kissimmee with only a swimming pool and a small meeting room in the early 1970s, and added a modest gymnasium in the 1980s, finally emerged as a strong, full blown YMCA, thanks to this powerful grass-roots coalition of government and private backers. Community involvement remains high, especially in raising scholarships for those who could not otherwise afford to join a YMCA. Arrington remains involved with the Association as a metro board member, as does Osceola County Commissioner Ken Shipley.

OTHER BRANCHES FOLLOW SUIT

FROM ITS START in 1972, the small West Orange YMCA Family Center in Winter Garden served a largely rural, sparsely populated part of the county. Over the next two decades the area was greatly transform ed. With more than 100,000 residents by the late 1990s, it was among the fastest growing areas of Orange County.

The West Orange Y remained small and struggled financially from year to year. Serving the community effectively at this Family Center was a continuing challenge. In the gymnasium, said Barbara Roper, a branch founder, “You could play basketball, but you were right against the wall and could get your nose bashed.”

In 2003, the West Orange YMCA Family Center mounted an ambitious, $2 million capital campaign, with Bert Roper as campaign chair. He was ideal for the job, since his ancestors and their family citrus enterprise had maintained a continuous stake in the area since the mid-19th Century.

Bert and Barbara Roper decided to make a major commitment to the YMCA in their home community. Their lead gift of $1 million in the capital drive-the Association’s largest ever from a family – ensured the drive’s success. With that gift they expressed their belief and confidence in the YMCA as an essential pillar of the community that they had worked so long to build.

Bert Roper also garnered another major gift for the campaign. He had known another renowned citrus grower, the late Dr. Philip Phillips, and solicited the charitable organization that is his legacy. Both families had built their citrus businesses, and the Dr. Phillips ranch operations, over many generations. They decided to come together and give back to the community that gave them so much. One of The Dr. Phillips Charities matched the Roper’s $1 million donation to the YMCA building drive.

In recognition of the Ropers’ enduring leadership in the Association as well as at the branch, the West Orange Y was renamed the Roper YMCA Family Center in 2003. In May 2004, the Roper YMCA unveiled its all-new facility, first with a wellness center, full-size gym, multipurpose room, renovated child development area and family locker rooms. In October it followed with the teen center, lounge area and adult locker rooms. In all, the Roper YMCA Family Center encompassed 32,000 square feet.

The brand-new Roper Yin West Orange thus joined the new Titusville and Osceola County facilities in again changing the public perception of the Central Florida Association. The YMCA was seen more than ever as a catalyst for growth and community building in all of Central Florida.

ANOTHER OLD Y RENEWS

THE SOUTH ORLANDO branch, dating from the same era as the Roper YMCA, had similar challenges. Its population was undergoing rapid change and growing more diverse-41 percent of residents were Hispanic, 28 percent African American, 20 percent white 6 percent Asian and 3 percent of other ethnicities. Many languages were spoken there, and the diverse work force primarily filled service jobs in the hospitality industry. The community as a whole was financially challenged.

The local YMCA, dating from 1972, was in great need of a complete makeover to accommodate the growing community. The existing facility would close for demolition so that the South Orlando YMCA could be remade from the ground up.

In 2004, the Association named champions of the Central Florida YMCA to chair a bold building drive for South Orlando – veteran Metro Board Chairs Charles Bailes and Clarence Otis Jr. Both were respected business leaders. Bailes III, as president and CEO of ABC Fine Wine and Spirits, and Otis, now CEO of Darden Restaurants, a Fortune 500 company, were ideally positioned to enlist corporate support in an ambitious, $ 2 million capital campaign.

The Darden Foundation set the standard for the drive, with a large gift of $500,000. Then one of The Dr. Phillips Charitie s made an extraordinary gift of $1.5 million, a tremendous boost for this Family Center. Other gifts followed from ABC Fine Wine and Spirits, Bank of America, and the Chatlos and Holloway foundations, among others.

Orange County earmarked $500,000 for the new Y, with plans to add a public park on South Orlando YMCA land. The City of Belle Isle donated $10,000 in honor of longtime resident and YMCA volunteer Jo Trimble-a first for this municipality.

Significantly, the South Orlando effort was a unique partnership among three contiguous entities – a Presbyterian Church, the Little League, and the YMCA- that each own about 11 acres. Pooling their acreages, they could have a 30-acre site; use their land much more effectively in combining parking lots, for example, and have a far greater impact on the community. In this joint undertaking, the three partners and Orange County were able to maximize existing resources.

The YMCA viewed the revitalization of the South Orlando Family Center as a potential tipping point for the community. Combined with the YMC.As work in local elementary and middle schools, the facility redevelopment and partnership would offer a powerful way to expand the Association’s mission in a community greatly in need of staunch support.

Completion of the 20,000-square-foot, $4.2 million YMCA project was expected in 2006. Following the Association’s pattern in the past decade, it had met its initial fund-raising goal early on and therefore had the confidence to raise its aim by $1.5 million. South Orlando would be the 15th YMCA to be renewed in a decade that had added 12 all-new Family Centers- a total of $75 million in property development.

The Central Florida YMCA succeeded so remarkably by under-promising and over-delivering on its goals, Ferber observed. “Our style became exceeding the bar, and topping expectations, starting with the Renaissance Campaign. That builds tremendous trust in the YMCA’s ability in the community.”

The current YMCA leaders were realistic in what they promised, and unfailingly successful in what they delivered. The strategy adopted in 1994, of adding more Family Center locations instead of creating one imposing regional YMCA, had spurred the incredible growth that gave so many people a Family Center near home, school, or office, which they could easily reach by foot, bike, or car.

ENCOURAGING EMERGING YMCAS

NEWER BRANCHES ALSO needed restoration in the new century. The Wayne Densch YMCA in Pine Hills, primarily a programmatic branch until 2002, emphasized youth activities such as after-school programs, sports, and cheerleading. It also offered a “Character Academy,” helping children to focus on core values during quiet story hours, and a parenting support program. Both programs enjoyed support from one of The Dr. Phillips Charities.

In 2003, the Wayne Densch Y sold its Jennings Avenue site to Orange County for use as a community center, and consolidated operations in its Hastings Street building. Like other branches, Densch moved to a membership basis and had 1,500 members in 2004.

The Seminole County YMCA Family Center expanded to a more complete facility by investing $2.3 million in a 5,000-square-foot wellness wing, a renovated multipurpose and aerobic room, youth/teen center, and child development area. By adding a new front entrance and handicapped parking spaces, the Seminole Y was now a welcoming presence for the entire community. This openness had great impact on public perception of the YMCA as an institution the community could count on to support families and kids.

The South Lake County YMCA Family Center, still operating in a small space in Clermont, was the only branch not renovated or newly built in the past decade. Its surrounding community was in great need of family supports. The metro board and staff stepped up to take leadership of the South Lake County Y, leading the planning and strategy with an eye toward building in the future.

Volunteers in Apopka, the still largely rural area, where a YMCA was formed in 1886 and continued for nearly 30 years, were eager for a Y in their community. As in Osceola County, Apopka’s schools lacked a pool for swim teams and physical education, and the community lacked space for gatherings. A provisional board was formed in 2004, aiming to raise $250,000 to staff a YMCA program in Orange County’s second largest town. In July 2004, the county school board voted to purchase 8.5 acres west of Apopka High School in hopes of building a YMCA.

EXPANDING AFTER-SCHOOL ACTIVITY

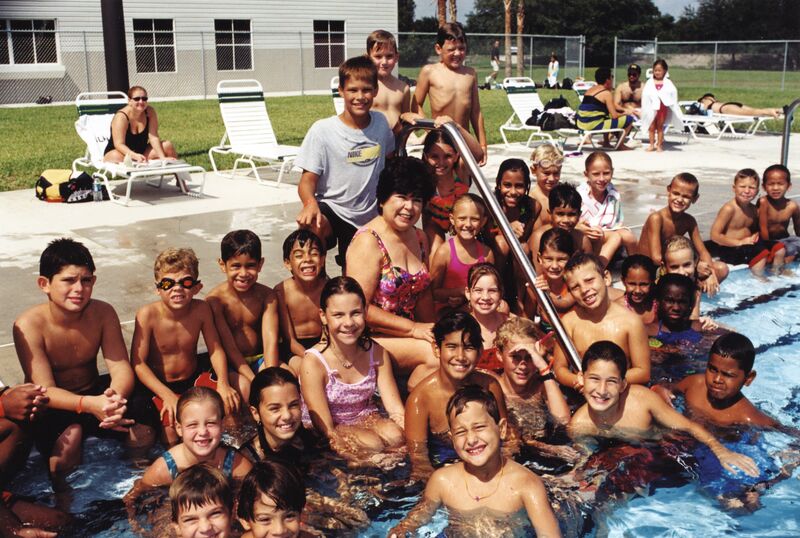

BY 1995, THE Central Florida YMCA had become the region’s largest child care provider. Families in the area, as in the rest of the United States, increasingly counted two working adults or had a single head of household, which created ongoing needs for quality care when many children were out of school without adult supervision.

During summer vacation, more than 20 YMCA day camps offered affordable care for 3,000 local youth every day. When schools were in session, demand was even stronger in the critical after-school hours, from 2 p.m. to 6 p.m. During that time many children returned home alone, with television their only companion. Bored at best and at risk of courting trouble, these “latch-key” children needed positive alternatives.

Traditional YMCA in-school programs, based on Hi-Y and related clubs, had emphasized character building and service. When Ferber joined the Association, the Central Florida Y started to rethink its initiatives in schools. After-school programs were strengthened by adding academic enrichment, with programs focused on math and science. The new efforts created awareness that “after-school is Y time,” said Ferber. Where branches had once run separate after-school programs, they were now centralized by the Association, to ensure a consistent educational emphasis.

In June 1999, Orange County health official Larry Jones told the YMCA that the new County chair, Mel Martinez, wanted to see after-school programs in all Orange County middle schools. No doubt inspired by his youthful involvement with Gra-Y (A Tale of Two Brothers p. 168), Martinez hoped the YMCA and the Boys and Girls Clubs would agree to run these programs, sharing a $2.7 million grant. The Association willingly joined in the initiative.

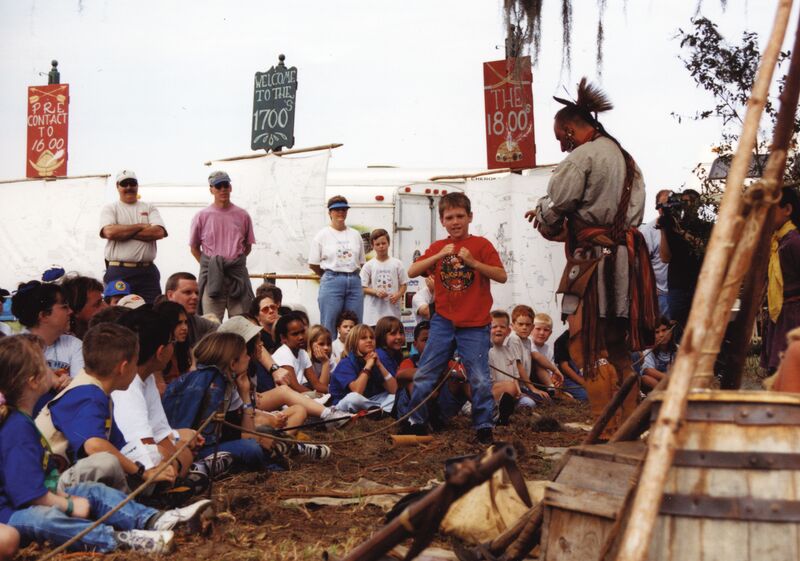

By 2004, the YMCA’s academically oriented curriculum was offered in 14 County middle schools and four elementary schools, serving more than 3,000 children each day. The programs, free of charge to families, provide students with positive role models as well as educational support. In addition to guided homework sessions, character development, physical activity, and tutoring, YMCA programs complement the standard curriculum. A popular rocketry program allowed students to launch rockets, making science come alive. Art and drama programs helped young people build self-esteem and confidence.

“The Y continues to make a big difference in kids’ lives,” observed Charles Bailes. “Unfortunately, every kid doesn’t have the opportunity to participate in [extra-curricular] activities. The Y gives them a place, a safe community, where they can develop character traits that are so important later in life. Kids are going to fill time with something, if they don’t have desirable alternatives … That’s the greatest service of the Y.”

SERVING YOUTH IN NEW WAYS

TEEN CENTERS WERE still rare in the Association, although greatly needed. One of The Dr. Phillips Charities agreed to fund a model teen center in 1999, at the Dr. Phillips YMCA. This branch, unique in having two indoor gymnasiums, was now the Association’s largest Family Center and could create a spacious, 2,000-square -foot area for teen activities. The new space for teenagers, named for former school trustee Robert A. (Bob) Simon, was a first in the Association. Subsequently one of The Dr. Phillips Charities funded another teen center, at the Osceola County branch.

The ever-popular Indian Guides programs continued unabated, although under the new name of Adventure Guides starting in the late 1990s. The then Brevard YMCA hosted a statewide Guides conference, where 2,000 participants launched rockets. Tribes that had been active in earlier decades in Central Florida still convened at alumni meetings.

Swimming lessons remained, as always, a prominent YMCA program since pools, lakes, and beaches were so plentiful and easily accessible in Florida. The accessibility was a cause for great concern, however, because drowning was the major cause of accidental death among children under age four in the state. Now, a new, research -based drowning prevention effort came to the YMCNs attention.

Safe Start, the Infant Swimming Research technique developed by Dr. Harvey Barnett and implemented by the Central Florida YMCA, shows one- to four-year-old children how to survive if they become submerged in water, by turning face upwards. Tom Ross, a longtime trustee of The Dr. Phillips Foundation, championed the effort, enlisting the Foundation’s support. The Foundation in turn asked the Central Florida YMCA to be its partner in this new instructional method and committed more than $1 million to the program. The Association readily agreed.

The six-week Safe Start courses began in 2001 at YMCA Family Centers, with instructors trained and certified in the technique. Since then, more than 3,000 young children in Central Florida have learn ed the survival swimming method, which remains controversial among some authorities who disagree on its effectiveness. The Central Florida YMCA, however, remains a staunch supporter of Safe Start.

In 2004, the Association also joined Orange County’s new Toddler Swim initiative, aimed at increasing community awareness about prevention of childhood drowning. A bilingual information service allows parents to dial 211 to locate instructional program s in their area. As a member organization of the countywide Drowning Prevention Task Force, the YMCA offers swimming and water safety lessons.

SUPPORTING THE DISNEY CAST

THE CENTRAL FLORIDA YMCA made a remarkable leap in 2004 as a child care provider. It cemented an alliance with the Walt Disney World Resort, following three years of negotiations, to help the nation’s largest single-site employer meet its employees’ most pressing need. Building on their long-time involvement, the two organizations forged an agreement that went far beyond anything previously seen, or imagined.

Walt Disney World had consistently supported the YMCA since the Renaissance Campaign. Harris Rosen introduced his neighbor Justin Green, then heading Disney’s Orlando operation, to Ferber. Since their initial meeting, the Central Florida YMCAs relationship with the entertainment giant has continued to grow. The corporation is represented on the YMCAs metro board and has support ed events such as the Black Achievers and Developing Hispanic Leaders galas, and the annual Celebration of Prayer. In turn, Ferber chaired Disney’s Teacheriffic Awards, which recognize teachers who implement the most creative ideas in schools.

In summer 2001, Ferber met with Disney representatives at the Magic Wonderland to explore some new ideas. What resulted would be a most unusual partnership, one that made national YMCA history.

Child care had become an enormous issue in the United States, and no less so at Disney World. For a decade, Disney’s 55,000 workers, or cast members had cited the lack of available, affordable child care as their top concern. The company’s biggest productivity problems occurred during 2 p.m. and 6 p.m. on weekdays, when children were out of school and parents were checking on or worrying about them. Employees needed child-care hours that matched their job schedules, and the 200 slots offered by Disney’s for-profit child-care provider could not meet the need. The dearth of care also made it difficult for Disney to recruit new personnel.

Realizing that the issue touched entire families, the Central Florida Association agreed to take the YMCA to Disney. Until now, the Association had provided child care only at its own facilities so parents could take part in YMCA activities, or in schools and other sites under YMCA control. Family Centers offered attentive care, but had no educational focus. For the Walt Disney World Resort, this trailblazing commitment to child care offered a unique opportunity to give back to the community it had so enormously transformed.

The Association made plans to build and staff an entirely new child-care initiative on the Walt Disney World Resort premises and hired Sarah Sprinkel, a seasoned child development professional, to head the freestanding, education-based operation. The branch would focus on the entire family, with ongoing events and celebrations of all national and cultural holidays. Since cast members represented many cultures and countries, the YMCA planned to help participants bridge those gaps to build trust, cooperation, understanding, appreciation, and respect for each other. “Diversity can drive us apart,” Ferber said. “This Center values everyone equally. There are strong family values across all cultures.”

To be truly family-friendly 1 the YMCA would not penalize parents who arrived late, as traditional child-care operations did. “We know that creates more stress for families, and we planned to reduce the stresses parents feel from competing demands at work and at home,” Ferber said. The Disney YMCA would also speak their language, be it English, Spanish, Haitian Creole, or Vietnamese, and would offer English classes for parents.

Chas Bailes, metro board chair in 2002, oversaw the complex partnership along with Disney’s YMCA Board member Maribeth Bisienere. Attorneys Tom Warlick, metro board chair in 1998, and Ron Sikes represented the YMCA in long negotiations. Chief negotiators for Disney were Tracy Swanson, David Henderson, and corporate counsel Jeff Smith. Ferber, Russell, Wilcox, and the YMCA executive committee were closely involved as well. The agreement was “painstakingly crafted,” said Bailes, and three years in the making. Since both sides had a similar goal of building strong kids and strong families, the goal was met despite some “heated conversations,” Ferber said.

For some executive committee members, the partnership represented an enormous leap; they remembered all too well when the entire Association ran on just $10 million-the price tag for this project.