PROGRAMS REACH FAR AND WIDE 1982–1992

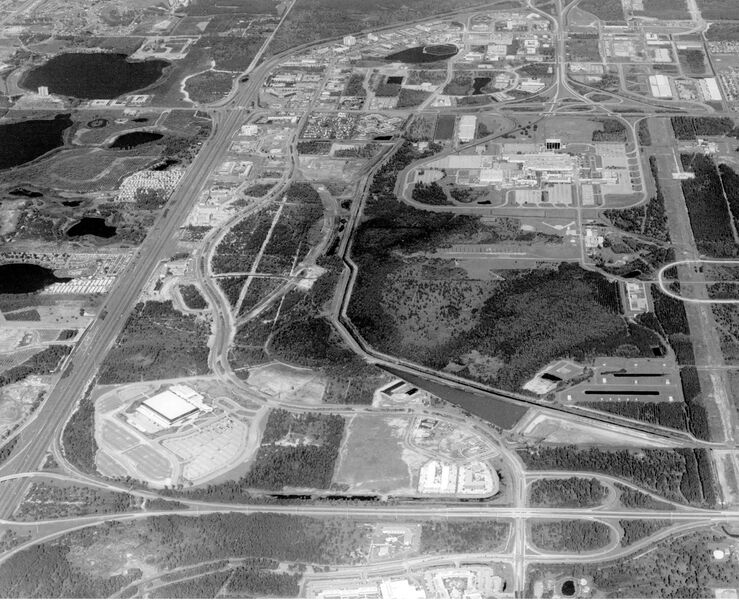

THE ORLANDO METRO area was a far healthier place in June 1982 when Jerry Haralson arrived to take the helm of the Central Florida YMCA. The prolonged economic slump of the 1970s had finally ended. Fuel shortages were now just a memory, and a spacious new airport was welcoming visitors by the millions to the area’s vacation paradise. By 1980, the Walt Disney World complex had become the world’s largest tourist draw.

International Drive, the site of many entertainment attractions, was expanding south of Sand Lake Road with a new convention center under construction. The Disney EPCOT (Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow) Center opened in October 1982. Although some skeptics at the time consider ed it another real estate scam, EPCOT too became a powerful tourist magnet. Central Florida had experienced some of its worst droughts and fires in January 1981, when 2,000 blazes swept through Orange, Seminole, Osceola, and Volusia counties, but they could not halt progress in the region—nor did the big winter freeze of 1982.

The Association, now nine branches strong and operating with a $ 2.5 million budget, had a clear horizon ahead. However, it was poised to resume its growth, which had stalled in the previous, economically daunting decade. Orlando continued its outward sprawl, adding new communities that were candidates for YMCA programs and services.

Haralson, having been vice president for operations at the Dallas Metropolitan YMCA, brought extensive program and administrative experience to Central Florida. The 36-year-old general director had trained to be a minister, but had never assumed a pulpit. After receiving an undergraduate degree in religion and philosophy at Sarasota’s Lakeland College, Haralson earned his master’s degree in theology at Southern Methodist University. During that time he also worked part-time at the Plano YMCA northwest of Dallas, where he was offered a professional staff position after completing graduate work.

Haralson joined the Plano YMCA full time as a program director, on a special two-year assignment from the Methodist Church. During his tenure on staff, he decided that “My ministry is the YMCA,” Haralson recalled. He later headed the Richardson (TX) YMCA before joining the Dallas Association staff. His move to the YMCA of Central Florida was “a continuation of that Christian ministry,” Haralson observed.

NEW BLOOD, RENEWING FACILITIES

HARALSON WAS SOON overseeing expansions at several struggling branches. “Jerry breathed fresh life into the Association,” said Evans Hubbard, who had served on the Metro Board since the mid-19 70s, in a 2003 interview. “He got us away from being a sleepy downtown Y.” Nevertheless, the new leader adhered to a traditional YMCA pay-as-you-go policy in building facilities. “Jerry and the board didn’t want to take on debt,” Hubbard observed.

However, Haralson was intent on getting the Association to grow again. One of his first actions was to complete the stalled South Orlando YMCA expansion, where increasing numbers of low- to moderate-income Hispanic residents, many of them workers at Disney, had growing needs for service. With the aid of Jim Brown, a locally influential volunteer, the branch raised $200,000 in a 1982 capital campaign, including a $55,000 match from the Central Florida Capital Funds Committee (CFCFC).

Brown had been reluctant to be involved in the campaign just six months earlier, but Haralson worked to convince him to lend his influence. Brown agreed, telling the new CEO, “I knew you wouldn’t fail at the first thing you did.” In 1983, the South Orlando YMCA completed the long-stalled expansion, including two courts for handball and racquetball, two additional locker rooms, a large multipurpose and exercise room, a fitness area, and a new front desk.

To carry out the Association’s work, Haralson hired “great young men and women” for his staff and managed them closely, Hubbard recalled. Haralson took pride in training a number of young professionals who went on to larger leadership roles in the YMCA movement. They included a Central Florida vice president, Randy Bugos, now heading the Savannah Association; camp director Skip Vogelsang, who heads the Pensacola Y, and Joe Warwick, Winter Park executive director, who leads the Augusta (GA) YMCA.

Another Winter Park executive in that era, Ron Edele, currently heads the Evansville (IN) ‘Y’; Bob Jacobs, a South Branch executive, now leads the Baton Rouge YMCA; Scott Washburn, who headed the Seminole County branch, is now Seattle Association vice president; and Danny Carroll, a Downtown executive, is in charge of the Hampton Roads (VA) YMCA.

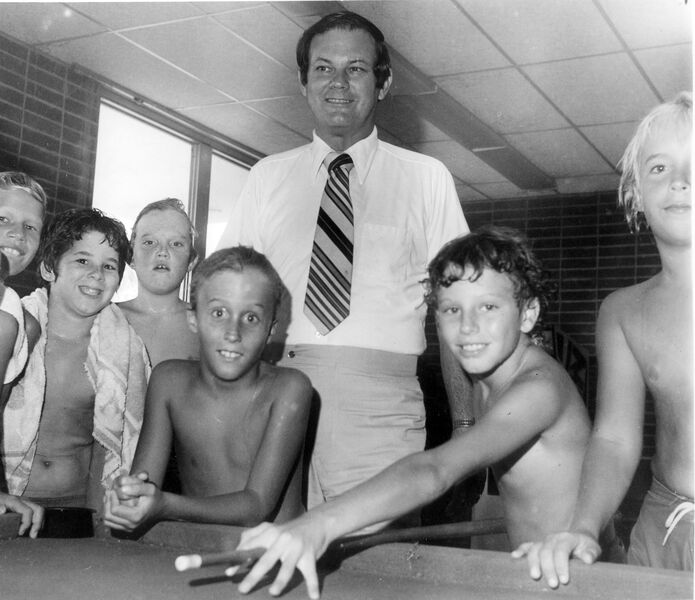

Haralson also recruited new directors who, like Evans Hubbard, had a perspective on the Central Florida YMCA from their youth. One of them, John (Chip) Webb, joined the board in 1984 while working at Peat Marwick, at the suggestion of his colleague Ralph Martinez. Webb had taken part in Gra-Y sports as a boy in Orlando, and he swam on teams at the Downtown and South Orlando pools. Haralson soon tapped Webb for the Association executive committee. That was “where all the action was,” said Webb, in an interview in 2003.

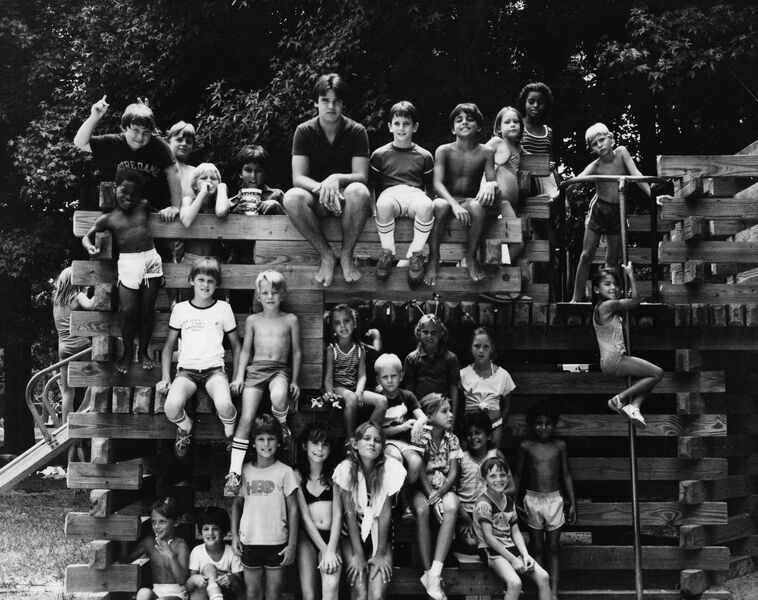

Camp Wewa, whose financial situation had distressed former Metro Board Chair Dave Horner, reported a turnaround by the end of 1983. Camping Services Board Chair Thomas H. Warlick announced a budget surplus of more than $14,000, compared to the year-earlier deficit of $25,000. Now the branch could focus on postponed projects, such as updating Wewa’s kitchen and food service area and acquiring some used canoes for paddling in Hidden River Park. The Orlando Sentinel continued to encourage financial assistance for youth who lacked money to attend Camp Wewa, with mentions in the Hush Puppies column and local Little Sentinels. The Caravan Camp continued to be a popular program, offering a spring break trip to Tennessee in 1984, followed by a summer junket to Canada and the West Coast.

BUILDING A BRANCH FROM SCRATCH

SHORTLY AFTER HARALSO arrived, the Association seized an opportunity to build a new branch from the ground up, in the Dr. Phillips planned community in southwest Orange County. The driving force was the local charitable organization by the same name. “I contacted the YMCA in 1982, and said, ‘We think there should be a YMCA,'” recalled Jim Hinson, chairman of The Dr. Phillips Charities. “They agreed.”

The late Dr. Philip Phillips, for whom the area was named, was not involved in the YMCA in his own time-but the philanthropy that bears his name provided eight acres of land for a local YMCA, giving the Association a $1 lifetime lease on the land. The Dr. Phillips Foundation also provided 26 acres for Little League fields that the new branch would manage. The gift embodied the Foundation’s interest in the “establishment and preservation of families and all that the YMCA stands for,” Hinson explained.

“The Dr. Phillips Foundation could have simply built the YMCA, but we wanted the community to feel ownership,” said Hinson. Haralson and Evans Hubbard, as branch board chair, assumed leadership of the community fund-raising strategy. Haralson recalled meetings on Hubbard’s porch where they set a goal to involve every young child and every local household, and crafted the strategy. They recruited Charlie McLandon, a former coach at Louisiana State University, to chair the local fund drive, and enlisted volunteers to work on canvassing through homeowners’ associations. By reaching virtually every household, the community drive raised $385,000. The CFCFC matched that effort with $325,000, so that no bridge loan was necessary on the building. The capital they raised went to construct an inviting new YMCA with a multipurpose room, lockers, office space, an outdoor pool, and athletic fields.

This was exactly how the Central Florida Association preferred to grow, paying with what was in hand. “We were a conservative board,” observed longtime board member Dan Ruffier, who presided over the Association in 1990–91. “We would never have dreamed of expanding by taking on debt.”

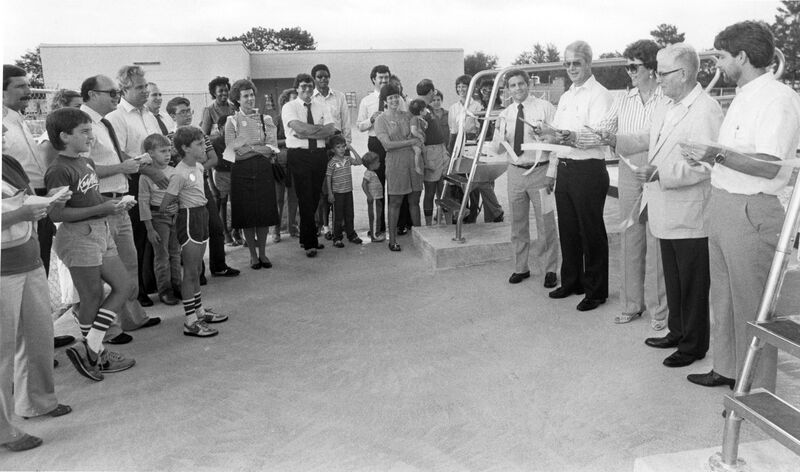

The Dr. P. Phillips YMCA Family Center opened its $570,000 home in October 1983. “As we hoped, the Y became the focal point of the community,” Hinson observed. Soon the branch facility would fill to capacity and need to expand to meet the growing demand for its services.

GROWTH BEGETS GROWTH

THIS NEW YMCA only made existing branches more eager to spread their wings. In 1984 the Winter Park YMCA had the opportunity to acquire a six-acre property in town from the Eastbrook Pool Association, for $38,000. “A guy at the Red Cross called and said, ‘I have a pool in a struggling neighborhood,'” Haralson recalled. “It was a beautiful, full-sized pool.”

The newly acquired site, renamed the Eastbrook Program Center, became an extension of the Northeast-Winter Park Family Center on North Lakemont Avenue. The Eastbrook property came with a 25-by-25 -meter outdoor pool that had one-meter and three-meter diving boards, a bathhouse, athletic fields, two tennis courts, and a multipurpose clubhouse of 1,500 square feet.

In 1985, the Seminole County YMCA program, which had operated for some years from a house in that affluent suburban area, officially became a branch and raised $660,000 to construct its own building. The branch sold its existing five-acre property behind Lake Brantley High School to the Seminole County Schools. In return, the YMCA took possession of 16 acres in mid-county, a green area south of Lake Mary High School on Longwood-Lake Mary Road. A permit to build was secured in June 1986.

On this new, well-trafficked site, the Seminole County branch constructed an outdoor pool, multipurpose room, office and locker space- and strengthened its identity and standing in the community when the new facility opened in 1987. “This gave them a grounding,” said Haralson, who noted that the branch soon became a leader in annual support campaigns.

Also in 1985, the South Lake County YMCA extension program in Clermont became a branch, with Mary Jamison as its executive director. As an extension, South Lake had hosted programs in local schools and other sites, but had always struggled to build a roster of community backers.

By 1988, the main Winter Park branch membership had risen to 21,000-more than tripling since 1984-and it had to turn away new applicants. The cramped branch also had to say “no” to adult basketball teams, bridge clubs, high school organizations and other groups wanting to meet there. The Winter Park Y also desperately needed room for teen programs, indoor youth sports, family workouts, and women’s classes. Latch-key children and senior citizen programs needed more attention, too. The branch developed a $450,000 expansion plan to add 6,500 square feet on Lakemont Avenue, which would allow it to serve 8,500 more individuals. But fundraising would proceed slowly.

SEEKING NEW FUNDING

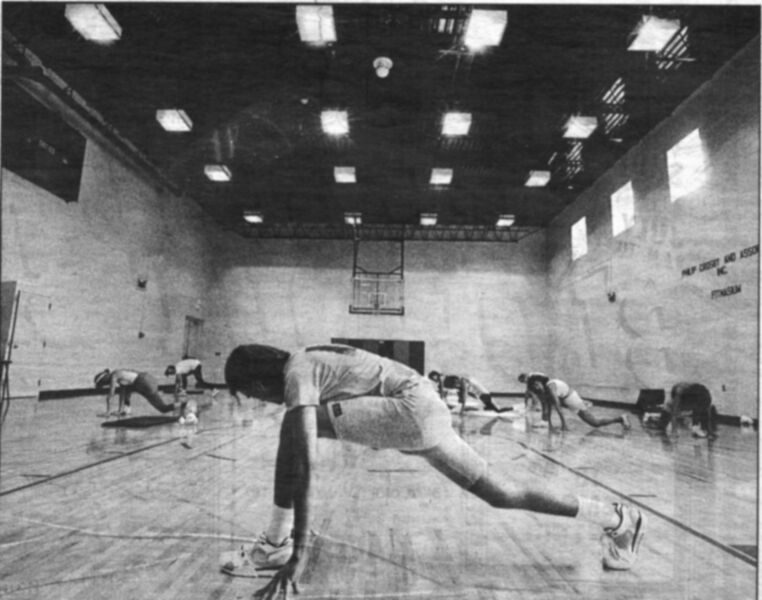

NOW 12 BRANCHES strong, the Central Florida Association conducted a comprehensive feasibility study at mid-decade. The results identified a need for $6 million in renovations and expansions at the existing YMCAs. A major reason for this need to expand was the nationwide fitness boom that began in the 19 70s and continued to grow non-stop in the 1980s.

Also known as “health enhancement” and “wellness,” YMCA fitness programs were aimed at helping people maintain “healthy lifestyles.” New exercise options, from Jazzercize classes to “Y’s Way to a Healthy Back,” continued to draw Central Floridians of all ages to area YMCA facilities. In 1986, the YMCA formally asked the CFCFC to fund six branch extension projects.

The CFCFC agreed to fund three of them: Tangelo Park, at $100,000; Osceola County, at $62,000; and Dr. Phillips, with $150,000. The Tangelo Park branch handily raised another $56 ,000 and began construction on an outdoor pool and a child care center in 198 7. In Osceola County, the branch on Kissimmee’s West Mabbette Street built an outdoor swimming pool and an addition with an office, gym, and locker room space. The Dr. Phillips YMCA Family Center mounted a drive for $800,000 and secured $545, 000 in 1988.

Left out of the CFCFC allocations were the Downtown, Winter Park, and West Volusia branches. Spurred by the need to identify and seek new resources for these unfunded projects, Haralson instituted more formal fund raising at the Central Florida YMCA. With a seed grant from the Edyth Bush Foundation, the Association staffed its first professional development office, to support both capital and annual sustaining fund drives.

The effort succeeded. The 1990 sustaining campaign, the yearly drive that allows the YMCA to offer scholarships and subsidize programs, raised more than $550,000 in 1990-nearly four times the sum it obtained when Haralson first arrived. The YMC& stated policy was not to turn people away if they could not pay. The enhance d fund-raising total would open branch doors to more families in need, disadvantaged youths, and citizens who otherwise couldn’t afford the going rates. More young people could now participate in YMCA sports, camping, swim lessons, and after-school programs.

The YMCA fund-raising effort was run efficiently and economically. In 1991, the Sentinel noted that the Central Florida YMCA spent $617,500, nearly 11 percent of its budget, on management and fundraising, well below the 25 percent benchmark considered appropriate. At the time, other major Central Florida charities were spending as much as 47 percent of budget in those areas.

Haralson also established a development committee of the board of directors. One key volunteer in the fortified fund-raising efforts was Dan Mahurin, now chairman and CEO of Sun Trust in Tampa. Mahurin had come to the YMCA “as a pup in day camp,” where he learned to swim and sing “Joy, Joy, Joy in Your Heart,” he recalled in a 2003 interview.

Mahurin began his career at the First National Bank at Orlando, where one of its bankers, John Sterchi, was renowned for leading the YMCAs triumphant capital drive in the mid-1960s. Mahurin volunteered at the Downtown branch in the early 1980s and then worked on the South Orlando branch sustaining campaign. Soon he joined the Association board, assisted with its annual fund drive, and served on the executive committee. Mahurin would chair the metro board in 199 5 and lead another very successful capital campaign.

The Winter Park YMCA mounted a drive for its $450,000 expansion, and by June 1988 had $275,000 in pledges; matching funds boosted the total to $461,000. In May 1989 the branch opened a 6,500-square -foot addition with an air-conditioned fitnasium that was half again the size of the adjoining gym; a large, open room for group fitness classes and youth programs; separate boys’ and girls’ lockers; and 24 additional parking spaces. Anticipating future expansion at the Downtown branch, Haralson purchased a fourth house on Shine Street which would later be razed for a parking lot.

The West Volusia YMCA added an extension program in Deltona in 1986, raised $350,000 in a 1988 capital drive, and added a Nautilus room, exercise and child care areas, and office space.

PERSEVERANCE IS GOLDEN

THE GOLDEN TRIANGLE Family Center, still operating out of an old church building in Eustis, was finally able to build in 1987. The branch had lost ground after Executive Director Cindy Ferguson’s departure in 1981. It took another year or so before Golden Triangle gained another high-energy executive, Diane Blair, whose arrival paved the way for a successful fund drive.

“She was the unsung hero of the Golden Triangle branch, with just the right degree of enthusiasm,” recalled its founding volunteer John Jackson. Before Blair arrived, he observed, “We were in the doldrums.”

Blair, in her late 20s, was working at a South Florida YMCA when she was recruited to the Central Florida Association. Her spirit and strong commitment to the YMCA, Jackson said, helped Golden Triangle to regain its lost momentum. Blair drafted a talented African-American teen, Derry! Benton, to assist in everything from coaching to directing after-school programs; as branch director of youth sports, he recruited his brother Kevin to help, along with Linda Comfort, who taught aerobics. “Derry! had a personality as dynamic as Diane’s,” Jackson recalled. (As an adult, Benton worked in banking in Tavares and served Eustis as mayor and city commissioner. He left Lake County to join SunTrust in Orlando in 1991, when Dan Mahurin was its executive vice president.)

This reenergized YMCA asked outside consultants to do a feasibility study. They recommended that it build a facility in stages, stating that the branch “would be lucky” to raise $300,000, recalled Jackson, who was once again serving as board chair. He remembered that the group’s reaction to the consultants was unequivocal: “You don’t know what you’re talking about. We’re going to raise $1 million.” In short order the branch launched a major capital campaign and did just that.

Bob Hester, a citrus grower and friend of Jackson’s, made an important contribution. He owned a grove eight miles from the centers of Eustis, Mount Dora, and Tavares-ideal for a YMCA that didn’t want to be identified with just one community (it also served the town of Umatilla). Hester, who understood that the YMCA did not have a lot of money, sold it 10 acres of land on David Walker Road in Tavares, near Highway 19A, for $20,000 an acre. The branch could pay him when it was ready, he said, at no interest on the balance. Hester also donated $100,000 to the YMCA and later sold it an additional 10 acres.

Other large gifts followed. Citrus grower C. V. Griffin, of Howey-in-the-Hills, gave $300,000 from his foundation to construct the gym. Another $150,000 came through Wilson Sheppard at the J. P. Donnelly Foundation, $65,000 of which built the pool. The Orlando Sentinel gave $30,000 for the fitness room, through the offices of Sam Fenton, editor for Lake County-” a big Y man,” Jackson said.

Years of effort paid off in broad-based support for this capital campaign. The community in rural Lake County raised a substantial amount. The final balance was nearly $1.2 million, more than vindicating the local volunteers’ optimism. In 1988, the Golden Triangle branch inaugurated its building. One of the early Y organizers did the land preparation and paving at cost, and volunteer Paula Stinson’s husband, an electrician, performed that work as an in-kind gift. No money came from government, and the branch refused United Way funds because they came with restrictions and fees. “What we raised stayed in the Golden Triangle;’ Jackson recalled proudly.

Diane Blair and Derryl Benton, by now a board member, took leading roles in the fund drive, but Blair departed six months before the building was dedicated. She had married a colleague, Skip Vogelsang, who was recruited to the Pensacola YMCA. Blair, who was succeeded by Jan Smith, returned for the inauguration to celebrate the community spirit that built this YMCA (The Little Engine That Could, p. 125).

PUTTING VALUES INTO PRACTICE

THE YMCA OF Central Florida was now on stronger footing, no longer operating hand-to-mouth. The Association had built up reserves and was able to look beyond its immediate concerns. Longtime Metro Board member Joan M. Ballard summarized the YMCA’s efforts in the late 1980s in a Sentinel article: The organization, she said, was focusing on five areas-promoting healthy lifestyles, strengthening the modern family, developing leadership qualities in youth, increasing international understanding between ethnicities and cultures, and assisting in community development.

Ballard omitted mention of Christianity or religion in describing the YMCA’s focus. But Jerry Haralson “always emphasized the ‘C’ in the YMCA,” observed Evans Hubbard. Haralson described the Central Florida Association during his tenure as “a very Christian YMCA. We were not going to apologize for our Christian heritage and purpose, but everyone was welcome.”

Haralson, in fact, wanted the Association to become more inclusive by deepening its involvement in community service, and by creating and operating branches and program centers in different areas. In 1985, he founded and chaired the Martin Luther King Commission in Orlando, which organized a parade of kids from all local youth agencies on the national school holiday commemorating the slain civil rights leader. The day featured a speech competition for youth, who highlighted Dr. King’s values.

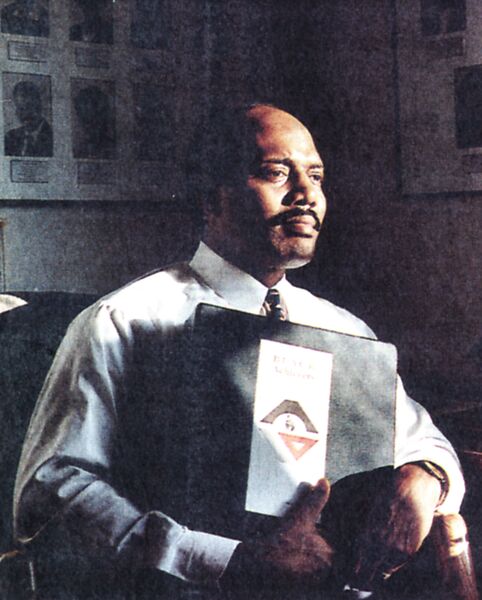

One of Haralson’s major initiatives for greater inclusion was · the introduction of the Black Achievers Program at the YMCA of Central Florida. Its aim was to recognize local African-American leadership and eventually, to diversify the YMCA board by adding new directors from the black community. Black Achievers was created at the Harlem (NY) YMCA in 1971 by a volunteer, Dr. Leo B. Marsh, to honor African-American men and women who were leaders and influencers in the community. Organizations employing black executives were invited to nominate candidates. The “Salute to Black Achievers” became an annual event in New York, and within a few years Dr. Marsh moved to implement the program in the national YMCA.

The Central Florida Association started planning its Black Achievers Program in 1987 and launched it in 1990, with the Orlando Sentinel as the founding sponsor. “We had to raise the money for an executive director and solicit the first participants,” recalled YMCA board member Geraldine Thompson, a founder of Black Achievers and its first co-chair. Local businesses agreed to “loan” managers to the YMCA program, and also contributed financial support.

The Achievers would in turn help students who were “falling through the cracks,” Thompson explained, by acting as mentors and role models for middle- and high-school youth. “They identify the Y as safe and connected.” W James Brown, a former teacher and school administrator who became director of Central Florida YMCA Black Achievers in 1992, emphasized self-reliance to the students, as the best route to economic progress.

The Central Florida YMCA honored 3 9 adult Achievers at the first Annual Black Achievers Banquet, which was attended by 300 people. In its start-up year, the program reached more than 200 young people. They met on Saturday mornings at the Orlando Public Library to discuss career- and education-related topics with their mentors. More than 260 youth participated the following year, with 34 Achievers acting as mentors.

Simmering problems had surfaced in 1990 at the 3-year-old Dr. Phillips High School. Animosities between students from the Carver Shores and Tangelo Park neighborhoods sparked violent clashes in March. As one teen told the Sentinel, “We just don’t have nothing else to do so we just fight each other.” Faced with suspensions and expulsion of students, parents and community leaders in southwest Orlando sought help.

Many of the school’s parents were single, often working two jobs and unable to supervise their children closely. Moreover, there were few organized activities for high school kids in the community. The conflict at this high school stirred the Association to create programs for area teens that could change the negative climate.

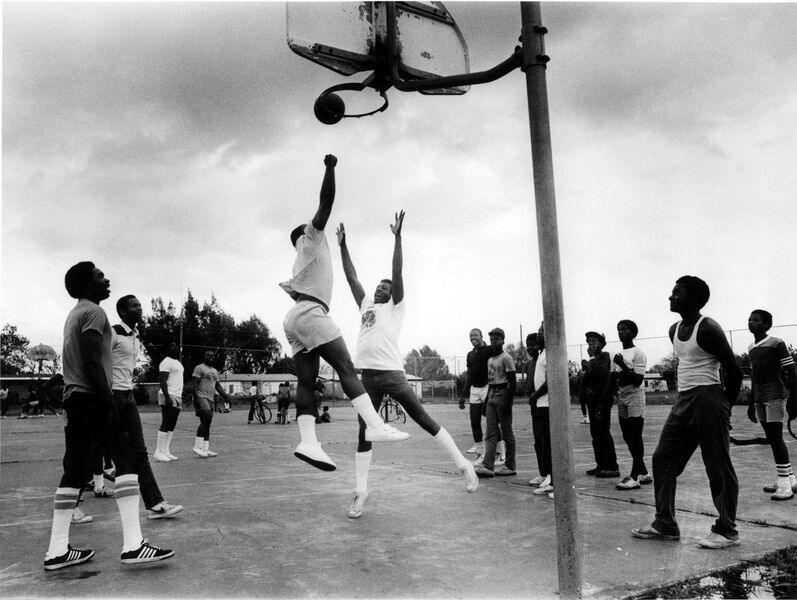

The Tangelo Park YMCA received immediate assistance from the Orange County School Board to develop a teen program. Bob Pickerall, director of the County’s Children ‘s Commission, awarded the branch a $26,000 grant for a summer initiative for 12- to 17-year-olds. Twenty-six teens took part in the 11-week program, which featured field trips; recreation; career, life-skills and self-esteem training; and drug awareness. Cultural activities, such as a weekend trip to Atlanta’s National Black Arts Festival, were included as well. The branch hosted a Back to School Fair in July to gather used clothing for local families in need, and the summer program participants staged an August Sock Hop at the Tangelo Park Y to collect socks and raise funds.

Harris Rosen took an interest in this branch near his Rosen Centre Hotel, giving the Tangelo Park YMCA funds to construct a teen center. The Association also joined in wider efforts for at-risk youth. The Orange County School System implemented a “Safe Place” program for any young person who felt threatened or needed a refuge at any time. The YMCA agreed to help provide those safe spaces.

FURTHER EXTENDING THE REACH

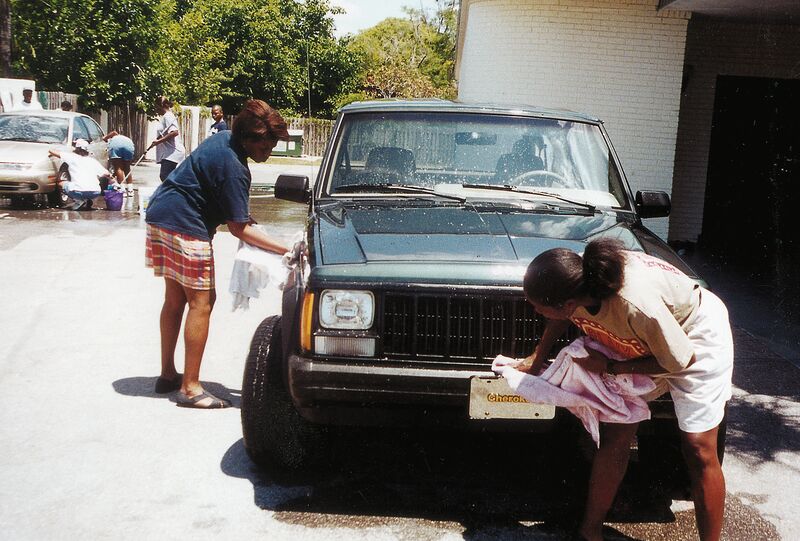

IN 1992, THE Central Florida YMCA moved to serve another disadvantaged community, Pine Hills, when it acquired a recreation center on Jennings Avenue formerly owned by the Robinswood Civic Association. The neighborhood was one of Orange County’s most densely populated; its 70,000 residents included many African Americans, and Jamaican, Haitian, and Hispanic immigrants.

Pine Hills was one of Orlando’s first subdivisions in the 1950s when the Martin Company opened its plant near Highway 50. The Robinswood Estates development had offered “starter” split-level homes for Martin’s workforce. Homeowners enjoyed the use of a 10-acre park with a swimming pool, tennis courts, a small building, and wooded areas. When Orange County took over the development’s mortgage and decided to sell the park, the Central Florida YMCA stepped in, seeing an ideal site for its after-school programs and sports leagues.

The Association bought the Pine Hills site as a program center for $306,000. “We practically bid for it on the courthouse steps,” recalled Haralson, who credited Jim Hinson of The Dr. Phillips Foundation with making it possible. Hinson’s attitude was “Whatever it takes,” said Haralson.

A storefront YMCA had opened in spring 1987 in Ocala, a modest rural community located 85 miles north of Orlando. The intent was to provide programs like after-school care and day camping in Marion County, and to create a teen center for local youth as an alternative to the streets. “They wanted something positive for kids,” Haralson observed. The Ocala-based YMCA considered remaining independent or joining the Gainesville Association, which was closer. The Marion County leaders decided to be part of the Central Florida organization.

The Marion County YMCA extension had done its best to meet local needs, but it was struggling without a permanent home. Its day camp used four different sites in four years; parents with kids in Y programs at different sites had to make the rounds of town. Pressed for facilities, Marion County YMCA volunteers launched a $1.5 million fund drive in 1992 led by David Denyer, chair of its board of managers, and Jim Williams, who chaired the fundraising effort. The drive collected more than $180,000 from the YMCA’s campaign cabinet and board of managers alone. “It was a defining moment,” Haralson recalled of the successful drive. “They had community support and the right leadership.”

In July 1992, the Marion County extension became a branch. It leased 9.1 acres and built a facility with a 25-meter outdoor pool, gymnasium, exercise area, locker rooms, and office. The outdoors area provided court space, sports fields, and parking. Liz Whitacre came from the Gainesville YMCA, where she was a program director, to be the first executive director.

Also in 1992, the Central Florida YMCA forged a unique partnership when the Golden Triangle branch entered into a joint venture with the private Waterman Hospital, constructing a 12,000-square-foot addition to the YMCA in Tavares as both a fitness center and physical therapy out-patient unit. The expansion helped the branch resolve its growing pains; it had grown from 300 members at its opening five years earlier to more than 3,000. This was the first YMCA partnership with a hospital in the nation, and became a model for future relationships with medical institutions.

HELPING FAR FROM HOME

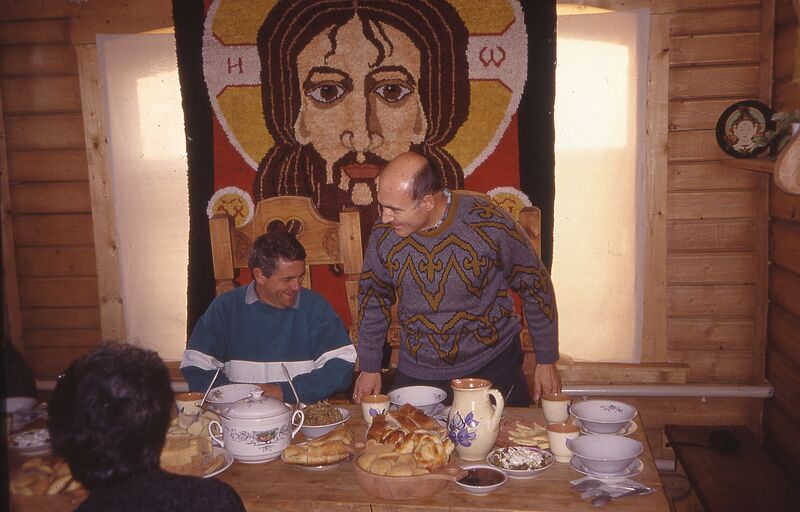

IN 1989, AS Mikhail Gorbachev was implementingperestroika in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), Haralson made a trip to Russia. The YMCA of the USA had been invited to discuss establishing Associations there. In 1991, he returned to help organize a provisional YMCA committee in the city of Omsk, in western Siberia.

The national Association had a long-standing interest in Russia, where a YMCA once operated. After it dissolved following the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, the YMCA of the USA safeguarded funds for its Russian counterpart until it could return to the country. The Paris, France YMCA helped to keep Russian culture alive in the 1940s by printing works banned by the communist government.

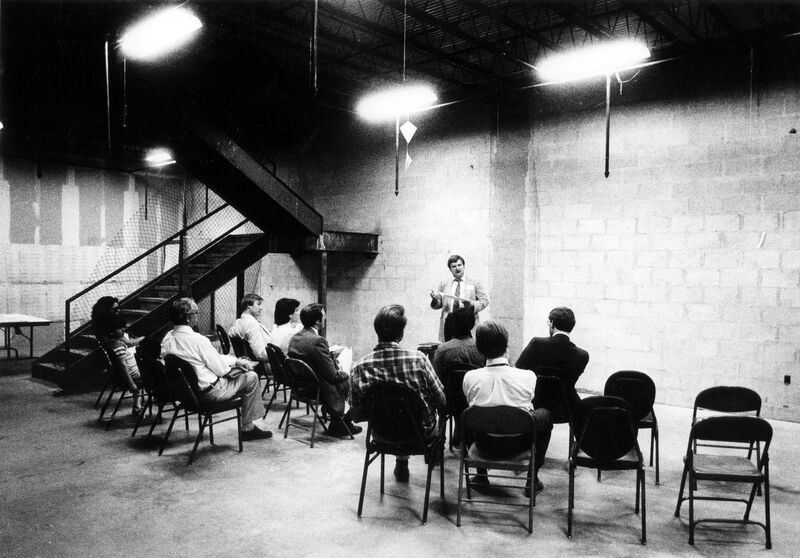

When the USSR was dissolved, the YMCA of the USA was formally asked to help restart Russian Y s. Haralson made a third trip to the country in October 1992 as part of a 12-member YMCA delegation that included Chris Becht, a Central Florida YMCA board member and manager with AT&T The Russian Parliament and the Russian Orthodox Church asked the delegates to aid five start-up YMCAs, including the one in Omsk, by fostering cultural and educational growth and volunteer work among Russian youth.

The emerging republic’s YMCA leaders—24 in all—visited the United States in an exchange program, and the Central Florida Association hosted two of the Russians. They studied all aspects of YMCA work, including volunteer involvement. “Volunteerism is uniquely American,” Haralson told the Orlando Business journal in November 1992. It was virtually unknown in the Soviet Union, he added, where “you were paid for everything.”

The Central Florida Association also sent four young people, ages 19 to 22, to the Omsk YMCA for a several-month stint, and in return four youth volunteers from Omsk would come to work at a Central Florida summer camp. The Association in Siberia also wanted to teach English to meet a growing demand there, and sent two volunteer teachers for a month in Orlando to enhance their teaching skills.

“I’ve caught the spirit that there are people around the world … that need the Christian influence of the YMCA,” Haralson told the Sentinel in December 1992, pointing out that Russian youth had never experienced Christian education.

TURNING ATTENTION TO TEENS

THE CENTRAL FLORIDA YMCA’s child care and after-school programs continued to grow with the population-by 1990 Metro Orlando counted 1,225,000 residents, a 70 percent gain since 1980.

Camp Wewa continued to see full registration for resident camping, and the Association was setting a day-camp record with 1,000 campers per day. Six times each season, kids from all YMCA camps came together for an exciting activity, such as track and field days. On International Day, each camp chose a country, made a flag, and dressed like the native citizens. “It was a way for them to understand the world they live in,” Haralson said.

At this time, Orange County introduced year-round schooling to accommodate the growing population and following a theory that students would learn better without a long summer break. The move created additional needs for child care, and the Association responded with special programming: when kids were not in class, the YMCA offered positive experiences for them. It was like year-round day camp, Haralson said: “When kids were out of school, they were on the Y track.” The Association also started a number of after-school programs for children in low-income neighborhoods.

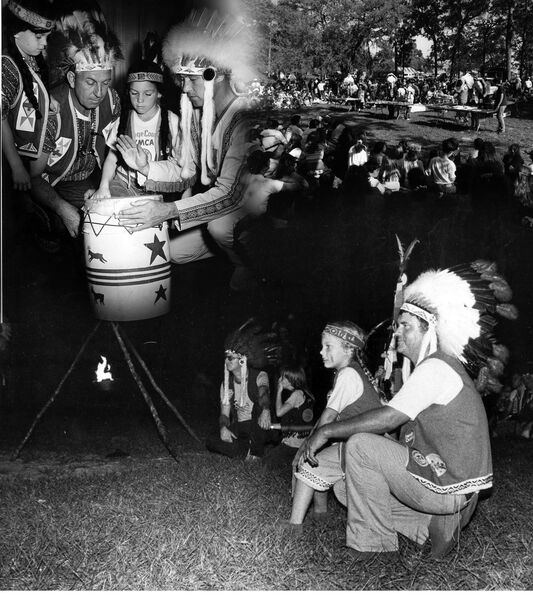

YMCA parent-child programs—Indian Guides and Princesses, Maidens, Braves, and Trailblazers—remained popular and widespread in Central Florida. Orlando hosted a State Powwow every year to great accolades, Haralson recalled.

Hi-Y and Tri-Hi-Y programs were on the wane here as they were nationwide, although the clubs remained in a few Central Florida high schools, including Dr. Phillips and Lake Brantley. Tracey Sullivan, since 1973 the sponsor of the Lake Brantley Hi-Y Club, received the Dr. Paul M. Grist Award for the southeast region in 1990. The annual award recognized outstanding service to the YMCA and its mission. A former board member at the Seminole County branch, Sullivan also served as a Youth and Government program facilitator. The Hi -Y she led was named Club of the Year in four separate years.

Most Hi-Ys, however, were being supplanted by the widespread YMCA Youth and Government program. That initiative was going strong in the Orlando-based Association; Haralson recalled sending 30 to 40 participants each year to state Youth and Government sessions in Tallahassee.

Overall, Central Florida’s teen population was underserved; most YMCA youth programs were designed for 6- to 12-year-olds. Programs for teenagers were generally difficult to start and maintain in the YMCA. In Central Florida, as in Associations nationwide, the emphasis had shifted to dues-paying health and wellness and programs for adults, and adolescents got short shrift. Fitness activities for adults yielded the revenues that increasingly underpinned YMCA operations, while teen programs were not self-fundi ng.

In 1984- 1985 the Winter Park branch had attempted to introduce teen dances. Business owner Dr. Albert Strickland, who sponsored the events, told the Sentinel, “From what I can determine there obviously needs to be a place for young people to congregate- some kind of structured activities which will help them to express themselves.” Decades earlier, he noted, organized social activities for youth were plentiful, but now many simply hung out on Park Avenue.

A Winter Park resident, Elaine Gray, helped organize the first dance and recruited her band, The Mix, to play in the mini disco setting. Junior high students responded with a good turnout of 150, but for the high school dance, only 10 older teens showed up.

Haralson decided to tackle the teen issue by asking every Metro staff member to design a program, rather than hiring a director for teen programs. He and staffer Carolyn Barr escorted teens on several sailing junkets in the late 1980s. One was a bareboat trip in the Bahamas for a dozen youth. Camp Director Skip Vogelsang took a group spelunking in caves, and Youth Director Bob Goddard organized canoeing trips and whitewater rafting. “These were times when we did exciting things,” Haralson recalled. Despite those efforts, however, Haralson said he was never fully satisfied with the Association’s work with teens.

EXPANDING, AGAIN

THE METRO AREA’S burgeoning population continued to strain YMCA facilities, even those that were relatively new. The 7-yearold Dr. Phillips branch in particular was heavily utilized. To meet community needs, the facility added a gym, Nautilus room, and lobby.

Unlike the Dr. Phillips community, the Osceola County YMCA in Kissimmee always faced challenges in fundraising. By reconfiguring existing space, it managed to add a child care center and multipurpose room that doubled as an exercise area. The Osceola branch had a number of “small victories,” recalled District Executive Mike Dungan, who later was its executive director for seven years. In 1980 it added a small, 7,000-square foot gym and office area, but the gym had only a concrete floor because the branch couldn’t finance the standard wood flooring. Later, it was able to add a small weight room and office area.

In 1991, still in need of capital funds at the Downtown, West Orange, and West Volusia branches, the Association mounted a $2.3 million drive, but the effort fell short. At the Downtown YMCA, where Dungan was then branch executive-recruited by his former colleague Haralson, from the Richardson (TX) YMCA-volunteers raised just $725,000 for a proposed $850,000 expansion to include child care space and offices for Association staff. The West Orange branch also came in short, raising only $340,000 of its $550,000 goal. Both branches could only proceed on a reduced scale.

To gain more support for these expansion efforts, the Association initiated a membership drive in 1992. This marketing effort, combined with fund raising, helped the Downtown branch secure enough funding to complete a 12,000-square-foot structure with a fitnasium, free-weight room, new running track, 80 parking spaces, and enhanced landscaping. An outdoor swimming pool was added on its south side.

The West Orange branch was able to complete construction on a fitnasium, fitness center, indoor racquetball court, lobby, and reception area. In West Volusia, the YMCA raised $658,000 to construct a gym, boosted by $500 ,000 given by Vesta Powell, in memory of her husband Andy. The branch opened its $761,000 addition in 1992 with the largest multipurpose space in any Central Florida YMCA at the time, featuring three new athletic courts for basketball, volleyball, and racquetball. By 1993, its operations were strong enough that the branch would withdraw from the Association and once again become a stand-alone YMCA, as allowed in its by-laws.

The Association’s extension programs continued to grow. The Winter Park branch assumed supervision in 1991 of a YMCA extension in nearby Oviedo. This program centered on youth sports, using local athletic fields, and had quarters in Oviedo’s Methodist church. In 1992, the Central Florida Association leased a 9.1-acre site in Ocala for the Marion County YMCA extension, and that program became a full-fledged branch in July.

OFFERING HOME SWIM

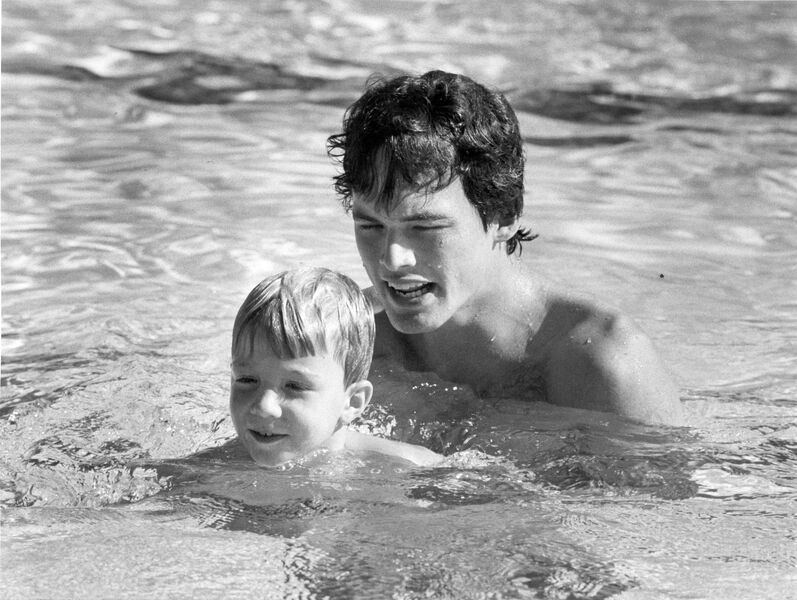

THE YMCA OF Central Florida offered numerous aquatic activities at its branches; in 1992 more than 4,000 youth took part in them. The programs included an annual “Learn to Swim” week, when YMCAs nationwide offered free lessons to the public.

When he came to Orlando, Jerry Haralson quickly grew troubled by the “huge” number of infant drownings in private swimming pools, which were commonplace. When a child drowned on his own block, he was stunned. “I decided I could make sure every kid could learn to swim,” the CEO recalled. Haralson worked to obtain state legislation that permitted the YMCA to create a “Home Swim” program that brought YMCA swimming instruction to private, backyard pools. Families would donate their pools for a six-hour period, and YMCA aquatics staff went from neighborhood to neighborhood giving lessons.

An unforeseen opportunity came about in 1992, when local swimmers found themselves abruptly locked out of one of Orlando’s best pools. The indoor Justus Aquatic Center was a treasured venue where Olympic records had been set. But this private Center on International Drive had failed financially and was shut down by Great Western Bank, the mortgage holder, without warning.

One of the surprised swimmers was Orlando hotelier Harris Rosen. “There were Special Olympians hovering about,” Rosen recalled in an interview. “One youngster recognized me as a swimmer and asked if they ‘d done something wrong, to have it closed. That made me very sad.”

Rosen quickly turned activist and took action against the bank, which planned to bulldoze the Center and replace it with a dinner theater. Rosen, who regarded the Center as “part of the fabric of the community,” mobilized other swimmers and divers for protest rallies that attracted press coverage. They were joined by a Special Olympics executive, who called the Center one of the nation’s finest facilities for teaching these youngsters. “They were painted as evil auslanders,” Rosen said of the bank “It hurt their business in Orlando.”

The hotel owner enlisted friends, including Arnold Schwarzenegger and other Hollywood celebrities, to withdraw “millions” from Great Western in Beverly Hills. He also created a nonprofit organization to which the bank could contribute the Center and receive a handsome tax deduction. Ultimately, the bank did agree to donate the Justus Center to a nonprofit organization- but not to Rosen’s.

Haralson contacted Rosen and asked if the YMCA could help. After a week Rosen called back and said, “Maybe you can.” Anyone who took over the Center stood to lose $200 ,000 per year on the operation. As the swimming enthusiast remembered, “I understood [the YMCA directors] were worried about losing money, so I said we’d take care of the shortfalls.”

The YMCA also turned to Orange County for help in making the project more feasible. The county responded by allowing construction of a billboard on 1-4, on its Convention Center property. The advertising resource, capable of generating at least $100,000 a year in income, would provide long-term revenue for a decade for what would become the YMCA Aquatic and Family Center.

Thus, after four months of meetings, the Central Florida YMCA acquired the Center as a donation from Great Western Bank, valued at $4.5 million. Business leaders in West Orange County, dermatologist Dr. Lucky Meisenheimer, and others helped the YMCA raise $600,000 for three years’ operating support.

Harris Rosen took the first dive in the YMCA’s newest pool, he recalled proudly. And Jerry Haralson received the YMCA’s largest Happy Hanukah check ever at the end of that year, from Rosen, by then serving on the branch board. It was made out to the YMCA Aquatic Center, for $50,000.

Now the YMCA of Central Florida owned one of only two competitive swimming centers in Florida, where it could host Olympic-style competitions as well as the signature swim lessons, lap swimming, and water exercise and aerobics classes that were so popular throughout its branches and camps.

Inserts and Footnotes

TIMELINE

1982: EPCOT Center opens in October; Tangelo Park branch initiated.

1983: Dr. P. Phillips YMCA Family Center opens; Orange County Convention Center debuts.

1984: Eastbrook Center acquired as extension of Northeast Branch.

1985: MGM studios announces plans to build. South Lake County YMCA opens in Clermont, Seminole County YMCA opens in Lake Mary.

1986: Northeast branch is renamed Winter Park Family YMCA.

1987: Golden Triangle branch opens first building; Marion County YMCA extension formed; Tangelo Park branch adds outdoor pool and child care center.

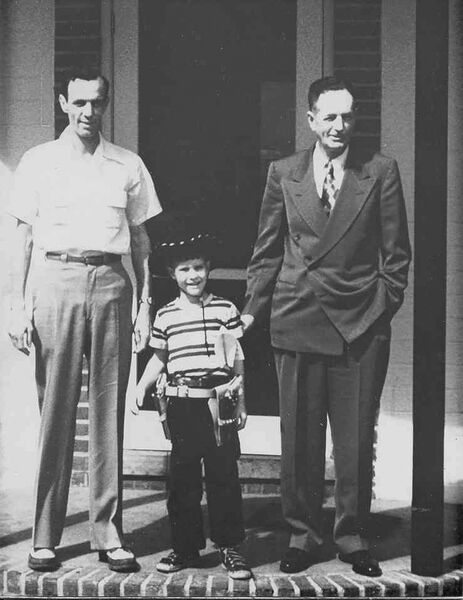

FROM FATHER TO SON: FRANK AND EVANS HUBBARD

FRANK HUBBARD WAS a key YMCA board member in the 1950s and 1960s. He retired in 1984 as the majority stockholder in the $70 million family construction enterprise his father had founded, which was subsequently sold to a global company with $400 million in annual revenues. Frank then started his family foundation, A. Friends’ Foundation Trust, with company stock.

When he reached age 65, Frank Hubbard decided to complete all terms on boards of organizations he served, but not to stand for reelection. He turned many of his civic duties over to his son, Evans, while remaining a community advisor and emeritus or life member of various organizations, including five country clubs he had built. Frank also founded Orlando’s Citrus Club in the 1970s, worked nearly full-time raising funds for Orlando Hospital, and spearheaded a $38 million drive to build the Orlando Science Center. “I was a great fundraiser,” he recalled in 2003. “There are not many doors I can’t open.”

When he left the Metro YMCA board, Franks son Evans took his place, just as Bill Phillips was assuming the CEO post. Evans had participated in YMCA activities since his childhood as a senior at Edgewater High School, he was Hi-Y president, where he performed community service projects and played sports. Phillips was his Hi-Y advisor. “I had a great mentor,” recalled Evans.

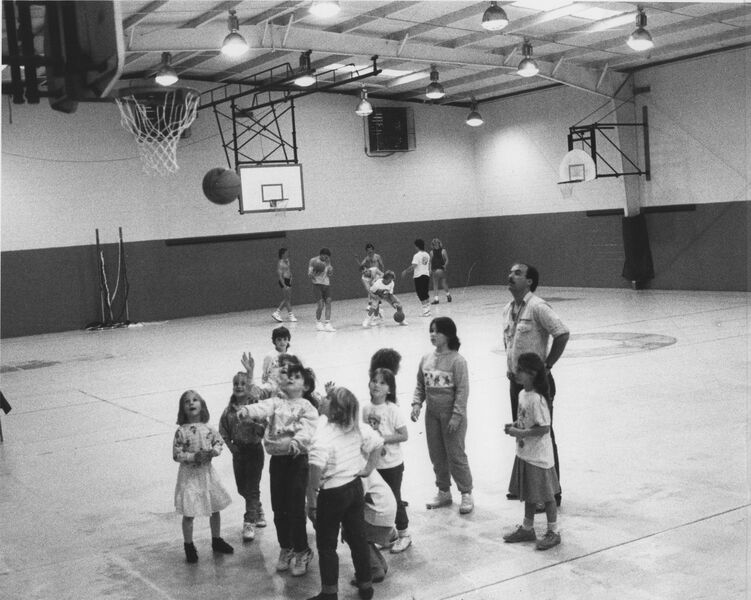

As a college student, Evans Hubbard worked part time as an estimator for his family company, when it built the first jogging track behind the Downtown YMCA. “It was one of my first negotiating projects,” he recalled “We did it at cost.” In the 1980s Evans chaired the board of the Dr. Phillips branch and led its building drive; he still coaches basketball teams there. Hubbard remained on the Metro YMCA board through the early 1990s.

THE LITTLE ENGINE THAT COULD

DIANE BLAIR, FORMER executive director of the Golden Triangle branch, returned when its first building opened in 1988 and spoke about the community spirit that created it. These are excerpts from that speech:

I feel like the Golden Triangle Y.M. CA. is the best example in the world if the Y.M.CA. spirit in action … A small but very spirited group got together 11years ago and gave a lot of time, energy, and hard work to get this Y.M.CA. started … They believed in the value of YMCA programs to enhance the quality of life In this community. And they believed hard enough and strong enough to make it happen … Some years were longer than others, and some years the spirit was stronger than others. But it always was there like the little engine that could, chugging along, determined and persistent, picking up steam every year.

We all know this community has changed in the last decade. Y.M.CA. programs have changed to meet those needs. Each year there are … more basketball players, swimming teachers, day camp counselors, board members, and soccer players. But the spirit of the Y.M.CA. is not a soccer game … (it) is that little kid who runs off the field on Saturday after the game who doesn’t know the score unless you tell him. He just knows that he got to wear that awesome raspberry-colored T-shirt and he was one of the guys who ran up and down the field while everybody cheered for him, whether he made a goal or not. He was one of the team. Nobody told him he wasn’t good enough or big enough or fast enough to play…

The Y.M.CA. spirit is not this building, but (it) is all those that made this building possible. We came here tonight to … acknowledge the people and celebrate the spirit that’s carried the Golden Triangle Y.M.CA. from that little church office in Eustis to this million-dollar facility…

A REVISED MISSION FOR THE ’90s

VOLUNTEERS MET IN August 1990 to draft a new mission statement for the Central Florida YMCA:

The purpose of this Association shall be to develop Christian values and improve the quality of life in Central Florida by involving individuals and families in programs that develop spirit, mind, and body.

It replaced this earlier statement:

The purpose of this Association shall be to help develop Christian personalities and improve the quality of life in Central Florida by strengthening families through the development of programs that are based on Christian values and extended to all persons in Central Florida.

THE ROPERS: A YMCA TEAM

BARBARA CRUCIGER OF Pittsburgh, PA met D Bert Roper when he was studying for a master’s degree in her home town. She moved to Central Florida with her new husband, where they established a home and had four children. In addition to her family responsibilities, she took an interest in politics and economics, her major subjects at Pennsylvania State University, and began to make her mark as a community leader.

Bert Roper came from a well-established local family, which had long been involved with the YMCA in Central Florida. His uncle, B. H. Roper, served as the YMCA director representing 1iVinter Garden in the 19 20s. Bert took part in Hi-Y, with Lenny Asquith as his leader; he too became a YMCA board member in 1949. In the 19 70s he engineered the land deal which allowed the West Orange Y to construct its first home.

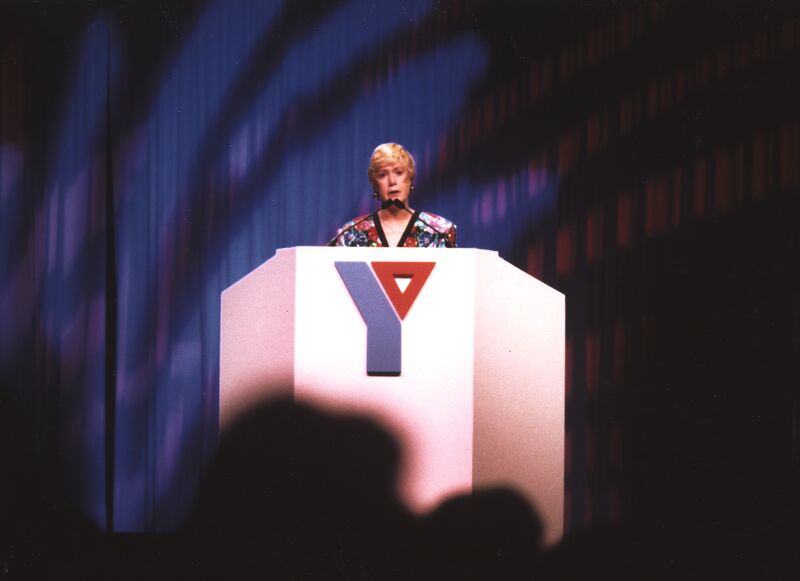

However, Barbara Roper didn’t rely on family connections in becoming a YMCA volunteer. Her initial interest began as a Camp Wewa parent; then she helped establish a YMCA program near her community in West Orange County. In the early 1970s she was tapped for the Metro YMCA Board Soon, as the Association’s delegate, Barbara Roper took part in regional YMCA meetings and task forces, represented the southeast at YMCA headquarters in Chicago and chaired a commission. “That brought with it a seat on the National YMCA Board,” she recalled, and the exposure paved the way for her election as YMCA of the USA board chair in 1990.

During this time, Roper also led an active professional life. She started a travel agency, Tops N Travel, in 19 83 and ran it for 18 years. When her work with the YMCA became “all-consuming,” her “excellent staff held body and soul together” at the agency, she recalled. Roper remains president of Contour Groves, the well-established family citrus business that Bert Roper runs.

The Public Broadcasting System (PBS), the East Central Florida Regional Planning Board and the League of Women Voters, to name a few nonprofits, have all drawn on Barbara Roper’s talents. She was the first woman nationally to chair a local PBS board, the first in Orlando to lead the local YMCA board, and the first in the nation to chair the YMCA of the USA board. The Ropers have left an enduring legacy in the West Orange branch that they have constantly supported. The $1 million gift they made for its latest expansion represented the Association’s largest donation ever. In 2004 the new West Orange building was renamed the Roper YMCA Family Center in their honor.