A THIRD TRY IN A TURBULENT ERA 1926–1941

BY THE 1920S, Orlando seemed to be on top of the world. Florida had been “discovered” by Americans living in less hospitable climates. Many made their way to Orlando by automobile on new state roads, seeking a sunnier future. The lake-strewn city’s relatively cheap land and commercial prospects were alluring, and its population doubled from 1920 to 1925, to nearly 25,000. Air traffic made its debut in 1922 at the new Buck Field, and the city’s first public library opened the following year. The advent of air conditioning in the city’s cinemas prefigured a new way of life in Central Florida.

With general prosperity riding high, Orlando’s city fathers were intent on widening and paving streets and securing sites for a city hall, incinerator, and other municipal facilities. The introduction of new dial telephones marked the city’s 50th anniversary, and Orlando’s first auto show, in March 1926, attracted multitudes to marvel at Packards, Pontiacs, Wills Sainte Claires, Lincolns, Hupmobiles, Pierce Arrows, Chryslers, and other new models.

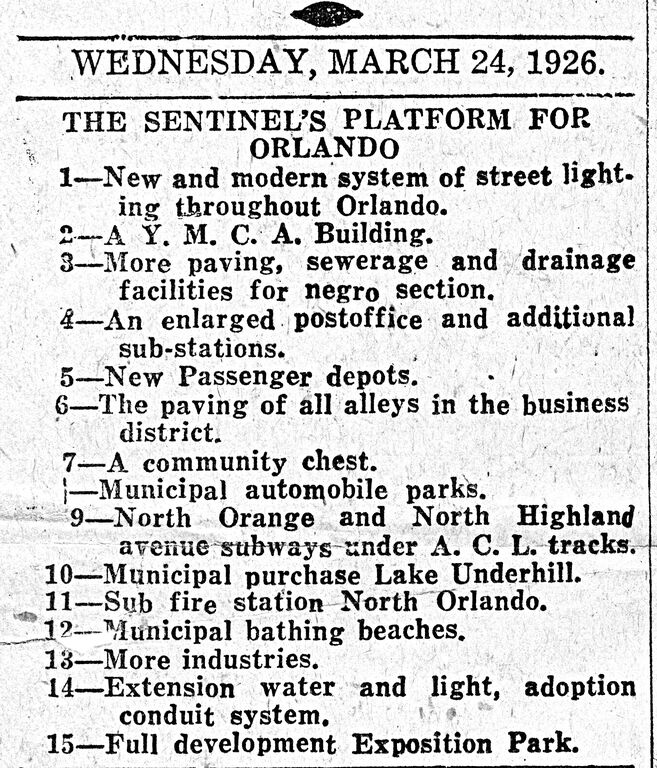

A dizzying real estate boom, fueled by the new arrivals, was reaching fever pitch by mid-decade. The Orlando Morning Sentinel, by now the city’s leading newspaper, polled citizens on what they most desired in their town. The results showed a YMCA ranking second among 15 possibilities, topped only by a modern, citywide system of street lighting. The public’s wish for a YMCA outranked all other civic necessities, such as an enlarged post office, new passenger depots, and more industries.

In 1925, some of the YMCA’s stalwart supporters gathered to reconstitute an Association and a board. They sensed that the time was right in Orange County to make a go of the organization that had twice failed to thrive. The mainstream Protestant churches Methodist, Baptist, Presbyterian, and Episcopal- represented a greater force than ever, both religious and social, in this fervently church-going city. To be sure, other creeds were strong: The Roman Catholic Church was well established, and Orlando’s Congregation Shalom had a permit to build a synagogue on East Church Street. Still, the Protestant congregations formed the strongest cadre. In this atmosphere, coupled with economic good times, the vision for a strong Young Men’s Christian Association once again rose to the fore. And this time, its organizers were determined to have the building that had eluded them in the past.

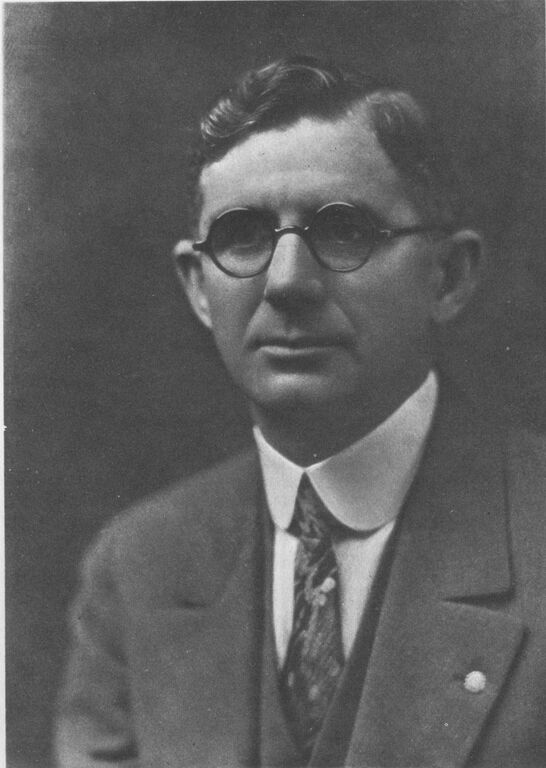

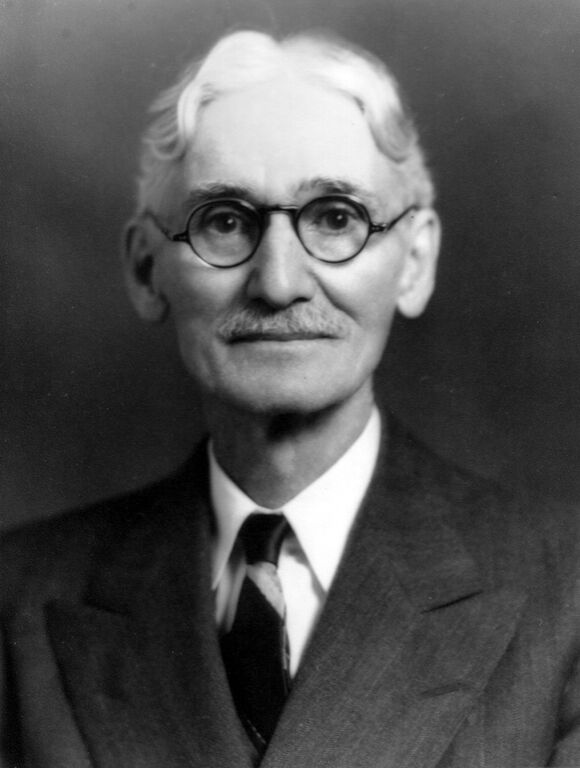

Once again, the YMCA leaders included some of Orlando’s most respected men. Newton P. Yowell, proprietor of the Yowell-Drew department store and earlier YMCA president, was among them. Yowell was not only a leading businessman and past president of Orlando’s Chamber of Commerce, but the town’s first Scoutmaster as well. His legendary young men’s Sunday School class at First Presbyterian groomed many of the city’s civic, business and professional leaders.

Also a city councilman, Yowell was “active in every progressive movement in Orlando,” observed historian Eve Bacon. Church member Walter Pharr, YMCA president in 1958–1959, recalled him as a fatherly figure that everyone loved.

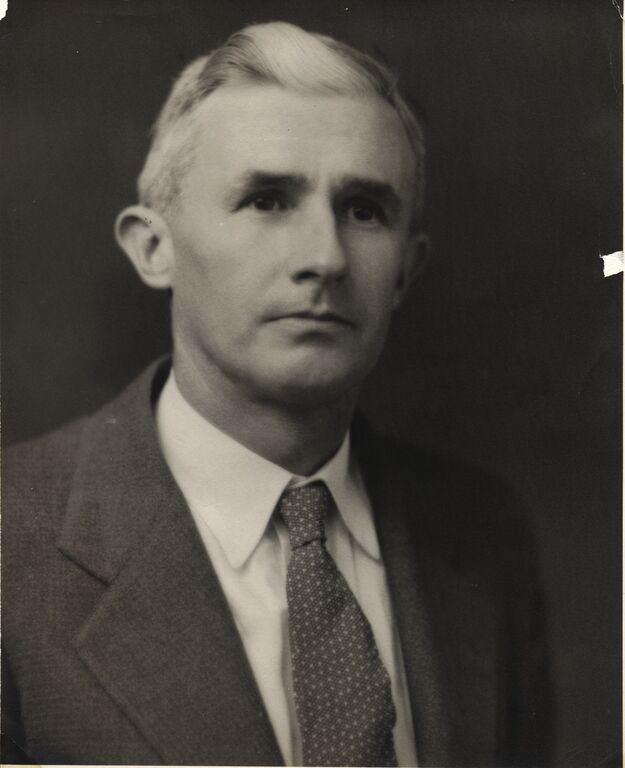

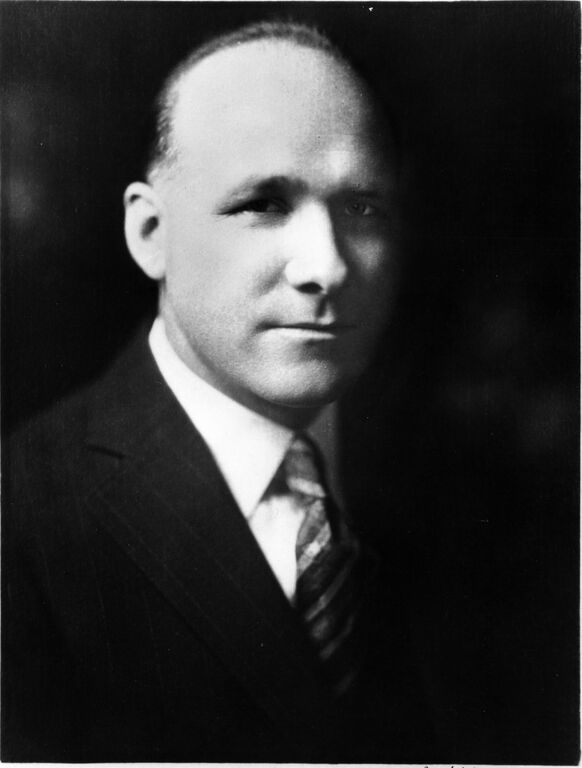

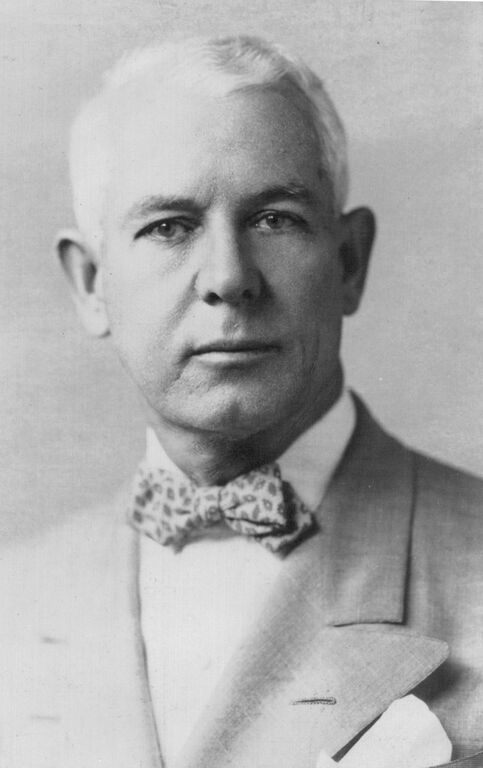

Oliver Pickney Swope, a Seminole County realtor, celery grower and commissioner who arrived from Kansas in 1913, was elected president of the Association. A member of the First Methodist Church of Orlando, Swope would chair the Florida Real Estate Commission for many years, appointed and reap pointed by five governors. Later, he would found the First Federal Savings and Loan Association of Orlando and preside over the State Building Savings and Loan League.

Eugene Duckworth, Yowell’s former business partner and the city’s progressive mayor from 1921–1924, also became involved in the new YMCA, as did merchant Harry Dickson and Judge Donald A. Cheney. A lawyer who had never practiced, Judge Cheney managed his family’s water business until it was sold to the city, but found his true vocation in working with youth. In 1919, Cheney had become the county’s probation officer and the following year created its juvenile court, where he served as judge from 1921–1933.

The Association was now formally called the Orlando and Orange County YMCA, to acknowledge its expanded scope. The Rollins College YMCA program, and the Hi-Y efforts in recent years led by the “county YMCA man,” E. J. Mileham, spanned towns from Winter Garden to Fort Christmas. Over time, the organization would simply be known as the Orange County Association. As their very first undertaking, Association members crafted an ambitious plan, in tune with the prosperous times: They would erect a grand edifice for their reinvigorated YMCA, and Yowell took the helm as general chairman of their building drive.

RAISING BIG MONEY

THE ASSOCIATION ENGAGED Samuel A. Ackley as a fund-raising consultant to guide the process. Ackley, then southern finance director for the national YMCA, was given an ambitious mandate: to achieve $800,000 in pledges. Proceeds from the drive would allow the Orange County Association to purchase a site where it could build an imposing structure. Ackley fully understood what was at stake. “It will be a great calamity to Orlando, Orange County, and the entire state of Florida if this drive fails,” he said. “Every Association in the country is watching us and we must not fail.”

The Sunday before the fund-raising drive began, nearly every church in the county took part in a “YMCA Sunday,” with ministers and outside speakers talking up the campaign to their congregations. Yowell hand-picked top business and professional men in the county as his colonels-Oliver Swope, C. A. Roberts, H. W Barr, William Edwards, and Harry Dickson- and tapped other captains for the drive starting on March 16, 1926.

The effort took the form of a week-long rally. Each evening, workers congregated at the temporary Stephens Tabernacle, which was adorned with banners proclaiming “Prayer Changes Things ” and “Service Is the Test of Greatness,” to report on pledges obtained. Women served refreshments, and high school boys and girls assisted. “Men prayed, and they worked as they prayed, “noted Florida Man Power, the statewide YMCA publication.

The first night of the drive, a Monday, captains reported raising $250,002-more than 30 percent of goal-and the second day they secured another $55,991. On the third day $48,000 in subscriptions came in. The following evening YMCA workers brought in commitments for $97,171. “From that day on the amount kept rising higher and higher as the flood waters of subscriptions were unloosed,” the Sentinel reported.

Lion’s Club President Charles Steven (Steve) Rybolt subscribed $10,000 from his organization, eliciting cheers from campaign workers. On Saturday, more than $39,000 was raised in four hours, and the total topped $540,000. Eugene Duckworth had obtained 61 subscriptions from his former company, now Yowell Drew, as two people worked the five-story department store in a second, thorough canvassing.

With more than $250,000 still needed by Monday, the last evening of the fund drive was truly a cliff-hanger. An air of hysteria prevailed in the Tabernacle. When all teams had reported in by 9 P.M., the YMCA was still $62,000 short of reaching its goal. The majority of those present vowed to fight it out, even if it took all night.

Appealing to the competitive nature of those who had previously pledged, the Association urged contributors to increase their assurances. Subscriptions began to roll in, at a thousand dollars or more per minute. Rybolt did not want the Lions to be overshadowed, so he ponied up an additional $500 to keep his club on top with $10,500. Judge Cheney, whose family had already sub scribed $25,000, kicked in another $10,000. Walter Rose promised another thousand if $800,000 were raised by midnight.

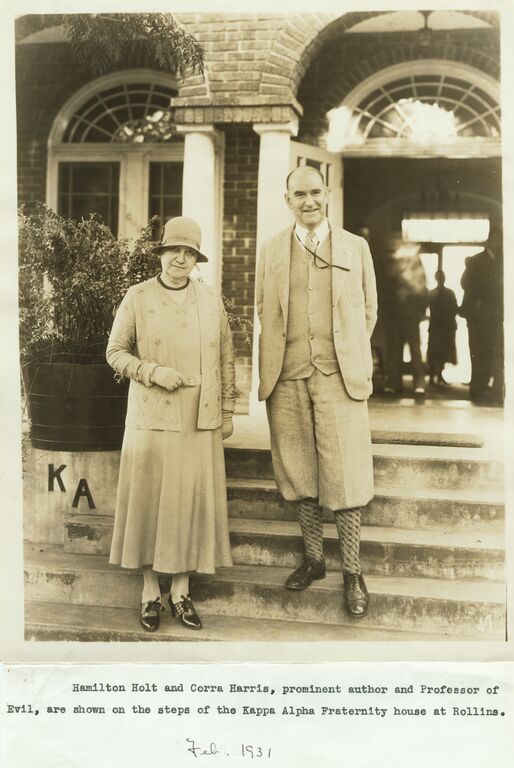

Dr. Hamilton Holt was among the boosters. The new president of Rollins College knew the YMCA well. After attending the Versailles Peace Conference, he had actively promoted the League of Nations, speaking at Associations nationwide about world peace- including the chapter at Rollins. Dr. Holt spurred on the Winter Park contingent, while Orlando Mayor Latta M. Autry came by to pledge another $2,500. Frank Haithcox worked the phones, pulling in several thousand dollars.

“Frank Currier brought an expert adding machine operator over with him from The Bank of Orange and even the machine could not keep up with the rain of pledges,” noted the Sentinels Town Slouch column. “At 9:45 P.M. the scoreboard read $797,400,” the Sentinel reported. With $2,600 still needed, YMCA President Swope and I.W Phillips, president of the Bank of Orange and Trust Company, put in $1,300 each. But it was Judge Frank A. Smith who put the drive over the top with his $500 subscription, the newspaper recounted, “as gifts began to pour in from all directions.”

OVER THE TOP

ACKLEY ANNOUNCED THAT the goal had been met, but the torrent of subscriptions was unstoppable. “When the $800,000 mark was reached you would have thought that you were in the New York stock market,” observed the Town Slouch. “Paper, unsigned pledges, table cloths, cards, in fact anything that the bunch could lay their hands on was in the air.” By the final count, at 10 P.M., the fund was nicely oversubscribed.

Campaign Chair Yowell, whose Men’s Bible Class had subscribed generously with the caveat that the YMCA be built as planned, “was observed sitting on the edge of the speaker’s table with a smile a mile wide on his face,” the Sentinel observed. “This was the crowning achievement of his life, and when the gang put the thing on ice his talk was worth hearing.”

YMCA board member Karl Lehmann, the newspaper continued,” was so chuck full of enthusiasm that he burst forth and gave the greatest talk of his eventful career.” Dr. Lehmann, a former field secretary for the Christian Endeavor Society with interests ranging from the Boy Scouts to the Beautification Commission, worked as administrator of the Monteverde School and served the county Chamber of Commerce as secretary. Another YMCA director, S. Kendrick Guernsey, a leader of the Methodist Church, led the ecstatic crowd in singing as he often did at public gatherings. Bacon wrote that Ken Guernsey was “a favorite visitor and speaker for Orlando high school students. He would lead them in the Orlando song.”

A huge banner headline topped the Sentinels March 23, 1926 edition. It declared, “Y TOTAL $804,700. Orlando and Orange County Go Over Top in Drive for YMCA Fund.” The line below declared: “Is Largest Sum Ever Raised in City of This Size in US.”

The Sentinels reportage perfectly captured the bubble mentality prevailing in Central Florida, and spared no superlatives in describing the YMCA’s victory. “With a mighty roar Christian Manhood swept to victory last night at the Tabernacle,” the story began. Pledges were “oversubscribed amid rioting scenes of frenzied enthusiasm and maddening paeans of thanksgiving.”

Despite the distraction of the shiny new Cadillacs, Studebakers, and Willys Knights in town for the auto show, the YMCA drive made big news because its impact was seen as more than merely local. The Sentinel pronounced it “the greatest campaign that has ever been held in Orlando or Orange County, in fact the entire world. . .. it means that Orlando and Orange County will have one of the finest YMCA buildings in the world.”

The newspaper touted the building crusade as a promising sign for all of Florida: “The confidence displayed,” it opined, “will go a great way to maintain confidence in this state’s financial soundness.” The results demonstrated “the prosperity of the solid central section of Florida, and the confident faith of its citizens in the future.” Surely the Sentinel could see the troubling economic signs that were cropping up locally and statewide. Florida’s inflationary boom was now at its euphoric peak, and the exuberant YMCA campaign was a symptom of looming problems. But for the moment, nothing could diminish the elation engendered by the Association fund drive, not even the gathering economic storm clouds. The YMCA leaders immediately began planning for the imposing edifice of their long-postponed dreams.

ENGAGING A GREAT ARCHITECT

THE ASSOCIATION MEN wanted an architect with a national reputation for their YMCA. They turned for advice to the Architectural Bureau of the National Council of YMCAs (formerly the International Committee), and the Bureau recommended Dwight James Baum, whom it considered one of the nation’s foremost architects. Baum had worked with renowned architect Stanford White, and was noted for his excellent designs and economy of materials and form. He had another YMCA building in the works, the West Side YMCA in New York City, which was taking shape as the largest freestanding Association building in the country.

Moreover, Baum was now spending two weeks a month in Florida. He had projects underway in the state totaling $6.52 million, including the $1.1 million Tampa Athletic Club, the Pasadena Country Club in St. Petersburg, and his most important commission in Florida, the $1 million Venetian-Gothic mansion “Ca d’zan” for the circus impresario John Ringling, in Sarasota. Baum was subsequently asked to build a YWCA in that city. The Orange County YMCA leaders, who were surely taken with his work in their state, enthusiastically commissioned him to draw up their plans.

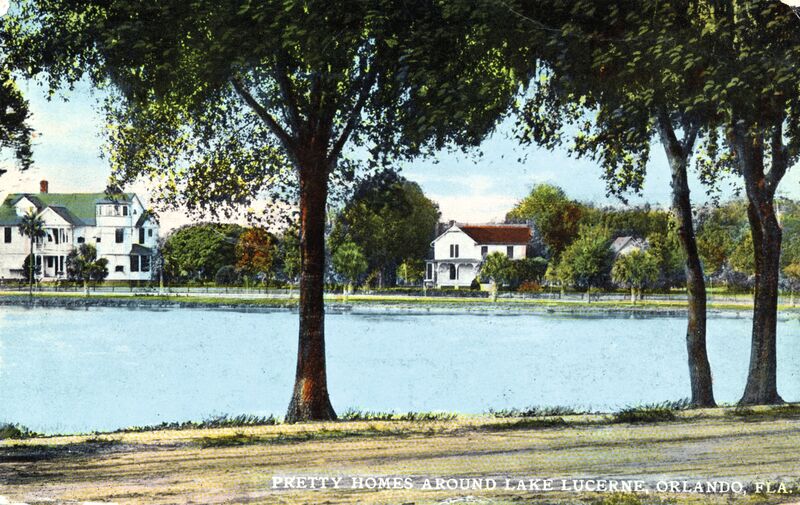

Baum had been a frequent guest at a home on Lake Lucerne, and was captivated by the idea of erecting a YMCA on Lucerne Circle. The 22-acre lake, surrounded by swamp cypress trees draped in Spanish moss, was the focal point of one of the town’s loveliest precincts. Dr. Philip Phillips, the major citrus producer and packer whose name would loom large in the YMCA in later years, had a showplace home at 135 Lucerne Circle, just east of a choice property the YMCA was considering- the northwest corner lot at South Main Street (later, Magnolia Avenue) and Lucerne Circle.

That property, as part of the estate of State Senator John E. Buxton, had been purchased in 1924 by seven businessmen, including Kendrick Guernsey, Giles, O’Neal, Swope, and Yowell, according to Bacon. The senator’s son, Benjamin C. Buxton, had respected his late father’s wish and remodeled the house on the property as a private businessman’s club. The buyers, largely champions of the YMCA, surely realized it could house a revived Association, and may well have bought it with that in mind. But in September 1925, they sold it to Victor Benar Newton, a banker and then general manager of the Standard Fruit Growers Exchange.

The YMCA site-finding committee culled 59 bids, but Newton’s lakefront property drew a unanimous vote. Fronting 183 feet on Lucerne Circle and 150 feet on Main Street, the lot was ideally located. All northbound and southbound traffic would have to pass the YMCA, making it one of the first public buildings that people entering Orlando from its new depot would see. Lucerne Circle was served by streetcar and centrally located to the business district and schools, where the YMCA sponsored programs.

The Association was highly aware of parking issues- those popular automobiles now multiplying in the area would have to be accommodated-and this site met that test. With Lucerne Circle being widened, plenty of parking space was assured on Main and McKee Streets.

Just two months after the fund drive, the YMCA purchased the site on Lucerne Circle. Realtor Clyde M. McKenney, a member of First Presbyterian Church who represented Newton, accepted “a price that was well within the figure set in the [Association] budget that was drawn up at the time of the $800,000 building campaign,” the Sentinel reported.

The Sentinel’s report was jubilant: “Today the wish of the Senator is to be fulfilled. A club, so to speak, far exceeding his expectations is to be erected on the Buxton property at Main Street and Lucerne Circle. A club that will do more to build the moral and physical welfare of Orlando and Orange County than any other organization in the world. The Buxton property has been purchased by the Orange County YMCA! And here, midst the beauty and calm and quiet will be erected the finest YMCA building in North America. A building that will do honor to all of Central Florida and even the entire state”.

Association president Swope, noting that the campaign had been “heralded the country over as a record breaker,” was determined that the building’s setting, and its architect, would be as impressive as the pledge drive had been.

“When I tell people I am from Orlando,” Swope said, “they remark ‘Oh, that’s where you raised the big YMCA fund.’ When people like that come down here to Orlando, we must have something to show them that will be up to their expectations. We felt that the contributors would never forgive the organization if an inside lot were selected, so we bought this lake front property. It costs no more to have a man [as architect] of nationally recognized ability with a wide experience in our type of work, and we believe that our Orlando and Orange County constituency would be dissatisfied with less than the best that can be secured for our work.”

Baum designed a grand, four-story, Mediterranean-style building for the lakefront site, echoing a style so popular at the time in Florida. The magnificent property was to be graced by a terrace and an outdoor gym overlooking the water. His proposed sketch was published in the American Architect’s edition of February 20, 1927 (see illustration, p. 35). The lavish, ornate exterior view was put on public exhibit in both Orlando and New York City.

“The architectural presentation of the building will be nearly perfect,” the Sentinel declared. “The lake would make the planned dormitory rooms more desirable, and space would be plentiful for all indoor activities.” The paper went on to report that local YMCA officials and friends of the Association “are elated . . .

They all voiced the opinion that a better site could not have been selected. Its location, natural beauty, and environment all played their part in the selection of the Buxton property.”

The Association moved quickly to staff the organization and took office space at 21 East Pine Street. D.O. Hibbard, who had been hired as general secretary, recruited Walter A. Davis as boys’ work secretary, and E. J. Mileham as head of the physical education department. The May Day appointment of Mileham, the former county Y man in Orlando, merited an article in the Sentinel. Apart from the Hi-Y initiatives he had led, Mileham had “built up a circle of friends [in Central Florida] that is without a peer,” the newspaper reported. “It has been said that he is one of the best-known men in Orange County and one of the most popular.”

Hibbard disclosed that men from Louisville, Chicago, Denver and Newark had applied for the physical education position, but the board, knowing Mileham ‘s qualifications so well, favored him. Mileham had been an energetic citizen of Orlando, serving as roll call chairman for the first annual Red Cross drive in December 1917, along with Swope and Lehmann, and teaching Sunday School at First Presbyterian. “In my mind,” said Hibbard, “we could not have made a better selection and everyone who has come in contact with him will be equally happy that he has returned to the Y in this capacity.”

In addition to his physical education duties, Mileham immediately began planning for the 1926 summer season at the YMCA’s Camp Orange on Hickory Nut Lake, purchased three years earlier. Former Orlando Mayor Carl T Langford (1967-1980) recalled his childhood experience at that YMCA camp, in an interview for this history. He and other nine-year-old boys spent two weeks pitching pup tents, building campfires, and using them for cooking. “Cleanliness and compatibility” were the bywords he took from the experience. Parents could visit on Thursdays and Sundays, and young Carl’s father brought angel-food cake for all the campers on Thursdays, when fewer parents came. “The next year we were flat broke,” recalled Langford, who later joined the Hi-Y Club at Orlando High School (OHS) and served as its chaplain in 1936.

A DONOR DILEMMA

YOUNG LANGFORD’S FAMILY was by no means alone in being “flat broke.” By early 1927, the YMCA was faced with problems that could no longer be ignored. Fulfillment of its whirlwind campaign pledges had slowed dramatically. To boost payments, the Association hosted a “great rally” of subscribers at the Sorosis Club on the fund drive’s first anniversary, unveiling its plans for the YMCA building with considerable fanfare.

The Sentinel touted it as “one of the most important [meetings] held in the city in months.” The news article recalled the previous year’s triumph when “the eyes of the world were upon Orlando and Orange County” and “all those who enabled this city and county to raise the largest sum per capita ever raised in the world.” The real agenda of this public gathering, however, was to quell a mounting skepticism.

“Uncle” Sam Ackley, the campaign fund raiser, was brought in to perform damage control with the assembled crowd. He sounded supremely confident. “There will be no alterations or retrenchment in the plans of the YMCA,” Ackley declared, addressing the gathering “in the same happy strain that endeared him to Orlando people,” the Sentinel reported. “He said, ‘I know your county YMCA committee. They are your most successful, most respected, and most able business men. They have nothing up their sleeves. They are in possession of no facts that they will not gladly put in your possession.”

Ackley alluded to several suggestions for changes in the building plans, but he declared that no alterations could be made without violating the basis on which pledges had been made. Other Association leaders chimed in to endorse forging ahead with the plans and pro gram already underway. YMCA President Swope declared, “We went into this thing with our eyes open and we have a right to expect that the YMCA will fulfill its part of the obligation.”

Swope addressed one criticism in particular: that money was being siphoned from the building fund to meet current Association expenses. The terms of campaign pledges, he pointed out, allowed them to be used for expenses over a two-year period. Campaign Chairman Yowell reminded the crowd that, as president of Yowell-Drew, he represented the largest single subscription. He and his company had made their scheduled payments “and would feel badly if they were not allowed to go on and complete their pledge as originally made for the sake of the boys and young men of Orange County.”

Yowell was undoubtedly also responsible for support from his Sunday school class at First Presbyterian. The $2,400 class budget for 1926 designated $400 per year, over five years, for YMCA operations. Despite all the optimistic talk, the reality was inescapable. Even though more than 700 pledges had been paid in full, another 271-averaging $2,000 each-had five years to run. The amount in hand was insufficient to hire contractors with any assurance that construction could proceed uninterrupted. Nor would things get better anytime soon.

By October 1926-well before the rest of the nation felt its own financial pain-Florida’s economy had collapsed. A horrendous hurricane had hit Miami and Miami Beach in September, wreaking destruction and bringing the state’s frenetic land boom to a crashing halt as once fervent investors realized that Florida land came with no guarantees. The formerly unrelenting booster ism of the ’20s was gradually giving way to a gloomy pessimism that cast a pall over the entire state.

Though spared by that hurricane and another in 1928, Central Florida nevertheless experienced reverberations. Orlando and Orange County’s speculative land bubble burst quite suddenly, with foreclosures and fraudulent deals exposed in the overbuilt area. Since most local businessmen were involved one way or another in real estate, all sectors took the hit. Orlando Chamber of Commerce revenues tumbled precipitously between 1926 and 1927. Bacon noted in her history that the value of Orlando building permits for 1926, at $8.3 million, totaled only a few thousand dollars less than in 1925, but plunged to less than $2 million by the end of 1927. Sales dropped so drastically that the real estate industry successfully petitioned the City Council to discontinue license fees for salesmen.

The state’s boom reached bottom in 1927, and stayed there through the storm’s havoc in 1928. The summer of 1929 brought another catastrophe to Florida, a Mediterranean fruit-fly plague that caused the State Bank to close in August. The nation’s Great Depression would soon follow, foreshadowed by the stock market’s spectacular crash in October 1929.

The Orange County Association’s timing was terrible. As banks failed and unemployment rose, most of the YMCA’s outstanding pledges became uncollectible. The leaders barely managed to secure $90,000 in subscriptions, of which $60,000 went to purchase the site on Lake Lucerne and other proceeds went to pay architect’s fees. A $16,000 mortgage was taken on the property. Somehow interest payments were kept up for a time, but the YMCA would never build on the magnificent site and would eventually lose the coveted property, although it continued to use the house there well into the next decade.

A retrospective Sentinel article in 1949 observed that “the local Association enjoyed its greatest period of growth and its severest setback when the Florida boom ‘busted’, and the pledges were worthless. Payments on the building fund, which totaled some $60,000, came to a stop in eight months …” The paper erred, however, in stating that the Association itself was forced to disband after 28 months of financial difficulty.

It is not difficult to imagine the depths of the YMCA’s disappointment, and its profound public embarrassment after a drive that was touted as an exemplar to other Associations throughout the state and the nation. In his 1932 memoir, O’Neal captured the frustration that he and other leaders shared: “That the subscriptions were not paid, and the building not built, does not mean that it will not be. The present home, on Lake Lucerne, on South Main Street, is one of the finest locations in the south. Sometime there should be one of the outstanding Y.M.C.A. buildings of the south erected there.” The wounds from this failed building drive in Orange County would take many years to heal

ROLLINS PROGRAM FADES

THE SPECTACULAR BUST was also felt at Rollins College, and in its YMCA program. The Orange County Association officers had helped it to reorganize in 1926, “for the purpose of promoting the men’s growth in Christian faith and character.” A 1927 memo noted that officers had been elected for 1927-28 but they lacked a leader, now that longtime Secretary Ray Greene had graduated and moved on. Quite likely, the student-led effort also lacked the funds to hire one.

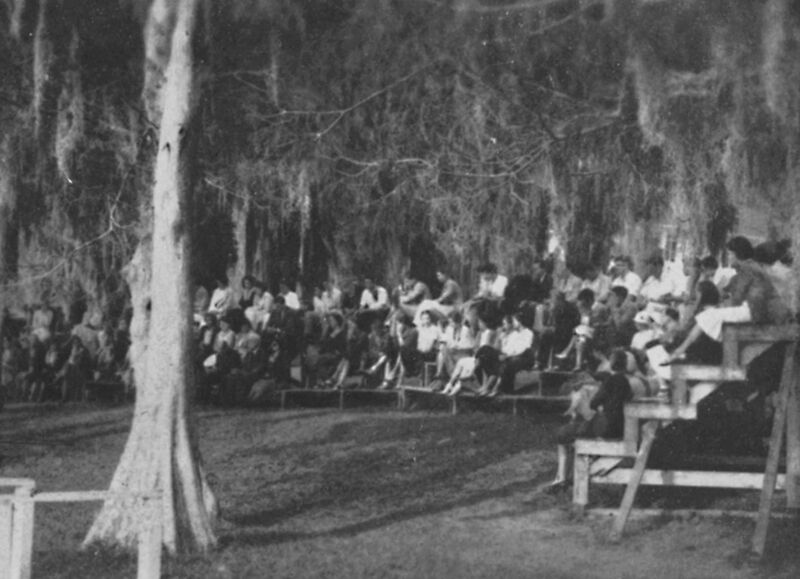

Nevertheless, the campus program carried on gamely. The student chapter introduced intramural volleyball and ping-pong at Rollins in 1931. One of the last records of Association activity on campus depicts a 1932 vesper service with YWCA members on Lake Virginia. The men and women continued to meet for informal discussions prior to a religious conference, and worked together to publish the Rollins student handbook and to host a “Y Mixer” for incoming students. The two organizations also operated a second-hand book exchange to help students struggling in the depths of the national Depression. Its profits went to charity.

VOLUNTEERS KEEP YMCA ALIVE

IN THIS ERA, YMCAs nationwide had become closely associated with the physical structures that housed their activities. Lacking a prominent building, the Orange County YMCA simply disappeared in many people’s eyes. The reality, however, was very different. Despite the Sentinels 1949 report, the Association did not disband completely. Certain YMCA leaders kept the work going, quietly and effectively, long after the fund-raising campaign imploded, and the YMCA was merely a memory for most of Orlando.

O’Neal credited two men for sustaining the organization’s work after the building effort failed. Judge Donald Cheney in particular was the YMCAs unsung hero, keeping it alive in Orlando and Orange County during the worst years. The juvenile court judge saw the Association as a necessary vehicle for building character in young people. Cheney, O’Neal wrote in his memoirs, “undertook organization along new lines, that of interesting young men [in the YMCA] in Orange County schools. He organized them into Hi-Y clubs, Triangle clubs, successfully carrying the work into all the high schools in the county.”

A reserved man, Donald Cheney worked in his New England family’s utility company from 1911 until it was sold back to the city in 1924. He made many contributions to civic life in Orlando for the betterment of youth, following the admonition of his father John

M. Cheney, also a judge, to “work for the future of young people.” Donald reorganized the Central Florida Council of Boy Scouts in 1922. In addition to his prodigious work with Orange County’s juvenile court, the younger Cheney founded the County Parental Home in 1924, Florida’s first, and created Orlando’s Board of Public Records and Playgrounds in 1925.

The juvenile judge regarded the continuation of YMCA programs during the Depression as an extension of his work with youth. He served as the Association’s unpaid general secretary, from 1931-1933. “It fell in his lap,” his daughter Barbara Randolph Cheney recalled, in an interview. From his bench, Judge Cheney was all too aware of the pitfalls awaiting vulnerable young men. Temptations were not hard to find in Orlando. The city failed in its attempt to get rid of slot machines in 1930, when Judge Frank Smith issued a restraining order against efforts by Mayor Giles and the police chief. Justice of the Peace Gene Duckworth tried to clean up the town’s beer and juke joints, but only succeeded in padlocking some of them.

The other steadfast volunteer during those years, O’Neal noted, was John Franklin Schumann. An Indiana native, Schumann was a lawyer and editor of the Orlando Evening Star. He was very civic-minded, according to his grandson John Schumann of Vero Beach. The grandfather was also a pillar of First Presbyterian, where he was an elder and young men’s Sunday School teacher. He, too, may well have felt that sustaining the YMCA was part and parcel of his church work. O’Neal, a fellow elder and Sunday School superintendent at First Presbyterian, praised Schumann for his continuous service as president of the Association.

O’Neal also revealed a little-known fact in his memoirs. Two YMCA professionals who had retired in Orlando, A. H. Whitford and Ward Adair, O’Neal noted, were recruiting other retired Association secretaries and their families to the city. Their actions were helping to keep the YMCA program and purpose alive in Central Florida, he observed. Among those transplanted elders was arguably the most revered figure in the national and international YMCA, John Raleigh Mott, who helped to create the campus movement that had taken hold at Rollins and many other colleges. Mott had also spearheaded the massive Association relief efforts during World War I.

Whitford, formerly with the International Committee, had spent his life in Association work and in retirement, served the Orlando YMCA as unpaid secretary during the Depression years. Some 33 Orange County men volunteered as Association directors in the 1930s, according to O’Neal (The Magnificent 13, p. 42), and Whitford’s voluntary leadership meant they had only to raise funds for incidental expenses and the interest on their mortgage. The directors included the young lawyer Campbell Thornal, who later became city attorney and eventually, chief justice of the Florida Supreme Court.

One of the YMCA’s activities in the 1930s was its Triangle Club for young businessmen, who met weekly in the house on Lucerne Circle. Barbara Cheney remembered the weekly suppers her dad hosted for them at the YMCA. His involvement was “something that had to be done,” Cheney’s daughter said. She recalled that sometimes a man would show up at a meeting and declare, “I’m one of the judge’s boys; he kept me out of jail.” Cheney’s wife and daughter helped prepare for these gatherings, covering a long dining table with brown wrapping paper. Suppers consisted of typical Depression fare, Barbara Cheney recalled, usually cold cuts and ham with baked beans and unheated rolls from the Federal Bakery. Sometimes her dad brought leftover lime ice cream home after an evening meeting.

The Hi-Y boys also enjoyed weekly suppers at the Lake Lucerne property, “famous for their spirit of companionship and friendliness,” according to the OHS yearbook. Kendrick Guernsey’s nephew Joseph S. Guernsey, a 1936 OHS graduate and Hi-Y member there for three years, attended some of those Thursday night bean dinners where the Hi-Y boys heard a fine roster of speakers, prominent men and civic officials such as Adair, Dean George Ezra Carrothers of Rollins College, Harry Dorsey, William Tilden, Whitford, and Yowell, who spoke to the youth about their lines of work. In 1927, the Boy’s Hi-Y at OHS renamed the Club for Newton P. Yowell.

Having kept up interest payments but lacking money for the mortgage, and perhaps for taxes due, the Orange County YMCA finally divested itself of the property in 1937, selling to two investor groups. (In 1978 this site was purchased for the Bowyer-Singleton Building, from the Orlando-Orange County Expressway Authority, which had torn down the former YMCA building. Bowyer-Singleton retained a carriage house, later a nursery school, on the site and built around it.)

YMCA devotees may have facilitated the Association’s pro longed stay there during the most difficult years. But now, as the local economy revived, buyers were emerging to snap up choice real estate, and under the state’s Murphy Act, those buyers would pay back taxes on properties. This brought an end to the beloved bean suppers, and certainly curtailed the YMCA’s already diminished visibility among adults in Orlando. All the same, the YMCA school programs continued unabated.

CLEAN LIVING, CLEAN SPEECH, CLEAN SCHOLARSHIP, AND CLEAN ATHLETICS

THANKS TO ITS successful high school programs, the Orange County YMCA continued to be an important community support during the dreary Depression years and the pre-War period. A Junior Hi-Y had been added for middle-school boys in 1926, and the Orlando Senior Club helped to install a Hi-Y in Sanford. Despite its struggles, the Association stayed current with the national YMCA’s focus and made sure that its young people could participate in those programs. By the mid-1930s, O’Neal noted, Hi-Y Club membership in Orange County totaled 140.

The OHS Hi-Y Club chose members at the end of each semester “on the basis of character,” with approval from a YMCA Committee – undoubtedly adults- and the school sponsor. (Principal Charles B. Taylor was a notably well-loved advisor.) The Club’s aim was ” to help the other fellow” and its watchword was “service. “The OHS members fancied themselves a force for good, declaring that they “would not allow the game of craps to be carried on in or about the school building. “This earned the Club’s vice president, Frederick Lewter, the moniker of “Lieutenant,” which followed him through his school career. The Lieutenant apparently took the Hi-Y motto, “Clean Living, Clean Speech, Clean Scholarship, and Clean Athletics,” very much to heart.

In 1926, some members attended the YMCA Older Boys’ Conference in Madison, WI, where the OHS Hi-Y received a silver loving cup for “exceptional participation in the convention.” Orlando students traveled frequently to state Hi-Y Congresses, hosting one in 1940. OHS Club members were among their school’s and the state Hi-Y’s-leaders: 1932 Club President Jack H. Kline was also the senior class president and “Most Likely to Succeed.” In 1933, Norman K. Brown, OHS Hi-Y president ex-officio, also presided at the Central Florida Hi-Y Conference, and was senior class president. The Tigando yearbook cited him as “Best All-Around Boy,” “Biggest Talker,” Biggest Boy Politician,” and “Most Business Ability.”

Donald Cheney Jr., Judge Cheney’s son, became Hi-Y president in 1934. Tragically, young Donald died three years later while a student at Rollins, in a car accident en route to a fencing match. Joe Gibeault, another OHS student, served as Hi-Y state president in 1936 and 1937. Harold Goforth, both local and state Hi-Y president in 1939, was his class’s “Most Dependable Senior” and “Most Likely to Succeed.” Ben Blackburn of OHS, the state Hi-Y president in 1942, represented Florida at the National Hi-Y Congress.

The Club installed a vocational guidance program and produced plays and vaudeville skits to raise funds for the YMCA World Brotherhood. It also initiated an All-Activities Night at OHS, where leaders of each activity discussed ways to cooperate, and an inter class track meet with the Varsity Club “to emphasize the plank of clean sports.” Members also tried to publish a school paper in 1933-34, but the Orange and White appeared only at irregular intervals. By 1938-1939 the Hi-Y’s social activities reflected then popular pastimes: hay-rides, dances, wiener roasts, and beach parties.

HI-Y PITCHES IN TO HELP

DURING THIS DIFFICULT era, the Hi-Y focused its concerns on those who were struggling financially. Before school opened in 1929, the Club organized a Second-Hand Book Store with more than 1,000 volumes for junior and senior high students. Book Store profits helped to finance the Club; by the fall of 1934, the Hi-Y bookstore earned more than $1,000 on the sale of textbooks. In 1936-193 7, a year in which free texts were distributed, the Hi y assumed management of the school supply department from the PTA. Club social service activities from 1933-1935 included providing free lunches for a semester to “deserving” students. The Hi y also gave away many books, and consistently provided Christmas barrels of toys and food to “the needy of the town.”

Christian ties and activities were central to the Club, whose officers included a chaplain. In 1929, with the OHS Girl Reserves Club, the Hi-Y sponsored a “Go to Church Campaign” and reported “far reaching” results. In November 1930, the First Presbyterian Church hosted the Hi-Y initiation service. The Tigando yearbook of 1934-1935 describes “deputation work,” through which boys made presentations at various churches. From time to time they led devotionals at school chapel services, “which were of great benefit to the students,” according to the 1935-1936 yearbook. In 1940, the Hi-Y held a contest for high attainment in scholastics; service to school and community; and attendance at church, Sunday school, and Christian Endeavor or League meetings. “Next year,” Tigando commented, “on the Hi-Y bulletin board there will appear posters, each calling to mind the foolishness or some fault of which we may all be guilty,” as a means of upholding high standards of Christian character.

After the Girl Reserves disbanded in the 1930s, the Girls Hi-Y, inactive since 1925, was reconstituted at OHS in 1936 with 50 members. Again, its purposes were identical with those of the Boys Hi-Y. By 19 39 the Girls Hi-Y had become “one of the most active clubs in the school,” according to Tigando, sponsoring a cookie sale, Christmas baskets, scrapbooks, and Easter baskets for the children’s ward at the hospital. In 1939-1940, after war began in Europe, the Girls Hi-Y led the Red Cross Membership drive, declaring it “the most successful drive of this kind ever” at OHS. By 1942, their efforts were primarily focused on defense and Red Cross work.

Nevertheless, the Girls Hi-Y managed to host social activities, such as an annual dance, picnics, and assembly programs in honor of Mothers’ Day. In 1940-1941 it changed its name to Tri-Hi-Y, following the national organization, and held a “Bundles for Britain” dance and a roller-skating party. In 1942, the OHS Tri-Hi-Y hosted the Tri-City Convention and a skating party at the Coliseum.

THE CITY SLOWLY REBOUNDS

JUST AS ITS crash preceded the nation’s, Orange County would recover sooner. The first hopeful signs may have come as early as October 1928 when, Bacon noted, the new airport was dedicated. The occasion sparked the “greatest municipal celebration Orlando had ever known,” with a concert by the Daytona Beach Boy’s YMCA Band and stunts by Marine Corps fliers. Every civic and fraternal organization joined in the parade.

Dr. Philip Phillips, a major citrus producer-the world’s largest, some said-conceived “flash” pasteurization in 1928, yielding a better-tasting canned orange juice, and opened a huge citrus packing house and a processing plant in Orlando. Thanks to its fortunate position in the agricultural belt, the city grew to be Florida’s largest citrus shipping hub. A continuing influx of winter tourists also helped to cushion the Depression years.

Mayor James Giles worked hard to keep local business afloat, sending out 4,000 personally signed letters by late February 1930 to all registrants at the Chamber of Commerce. In the early 1930s the economy improved slowly, although not steadily. At Orlando High School, the 1930-1931 Tigando poignantly reflected hard times in the city and the school. It was unusually thin compared to its predecessors, and the once-commonplace advertising from local merchants and supporters was missing. Instead, the editors thanked “loyal friends” for helping them put out the yearbook.

The Yowell-Drew Company went into receivership in 1932 and emerged two years later. In 1933, a financial panic caused a run on the First National Bank in Orlando and Florida Bank at Orlando. The institutions declared a five-day holiday and merchants cooperated by not selling goods. Judge Frank Smith halted foreclosures on home mortgages for owners trying to refinance, an essential move with many unemployed men now working solely for scrip. The Dickson-Ives store opened a “thrift floor” that year, and a “Buy Now” campaign and recovery parade led 10,000 citizens to march from City Hall to Lake Eola as planes buzzed above their heads.

Former YMCA Presidents Oliver P. Swope and Newton Yowell were key figures in helping the area’s destitute. Swope chaired Orange County’s Emergency Relief Councils and led successive federal initiatives locally, while Yowell served as director of District 6 of the National Recovery Act, encompassing Orange, Lake, Seminole, Osceola, Brevard, and Indian River counties. By late 1933, 3,400 Orange County men went on relief as the Civil Works Administration took effect.

In 1934, as regional director for the Federal Emergency Recovery Act, Swope became the target of a workers’ strike. Some 2,600 people stopped work for 17 days, accusing him of inefficiency and unfair practices. Many of the jobless were desperate as well; hold -ups and thefts had become routine in Orlando and according to Bacon, some citizens contemplated forming a vigilante committee. The city expanded its police force by 50 percent. But 1934 also brought encouragement when the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation was created. A new First National Bank at Orlando opened on Valentine’s Day with seasoned banker Linton E. Allen as its executive vice president and cashier. Local construction activity more than doubled from 1933. A new Kress “five-and-dime” store took a 99-year lease, and a solarium and beach, built with federal funds, opened on Lake Estelle.

Several YMCA leaders-Guernsey, Dickson, Holt, Giles, Leu, O’Neal, Schumann, Swope, and Yowell-along with the new publisher at the Orlando Sentinel, Martin Andersen, organized an “All Florida Show” to attract business to the area in 1935-1936. Although the men raised more than $100,000 by mid-1934 and worked to acquire 80 acres in Loch Haven for the project, the promised federal funds never came through and the grand plan failed in 1935. Investors never recouped their money.

Although money was still tight in 1935- relief for 3,500 men ended on July 1- Orlando hosted its first auto show in years in December, and the Works Progress Administration (WPA) allotted funds for airport improvements. Eastern Airlines began service in Orlando. O’Neal, by some accounts the city’s busiest man, led in reorganizing the First Federal Savings and Loan. He became its president, with Yowell as vice president and Swope-now WPA supervisor-as executive vice president. By 1936 recovery was palpable and the real estate climate was improving fast. Buyers were poised to grab choice properties like the YMCA’s Lake Lucerne site.

The three failed attempts at building a home for the Orange County YMCA unfortunately left an enduring legacy-a negative residue in public opinion. Despite the extenuating economic circumstances, “the YMCA got a bad reputation,” explained Dan Ruffier, a YMCA board member since the 1970s. “It couldn’t get anything going.” That impression was perpetuated by startlingly incomplete recollections, such as this rather terse account in Gore’s History of Orlando:

“The organization had gone heavily in debt by purchasing the old Senator Buxton place at the corner of Main Street and Lucerne Circle. For a time, the Y was operated at that location, but failure to collect pledges and the payments falling due on the purchase broke the organization and it lay dormant for a number of years.”

Otis D. Lundquist, as YMCA board president in 1954, summarized the sad legacy in the Evening Star, with some exaggeration: “It has been a long uphill fight since the boom days when Orlando provided for a million-dollar home. Those were the days when we thought only in five or six figures for enterprises. We didn’t have much cash, but we were long on promises and the million and then some was pledged. But the panic which swept the country soon after made the payment of those pledges impossible and the organization was worse off than it had been, because it had made commitments which it was never able to fulfill, and a lot of folks were sore because they had paid in cash and they saw no results for it.”

However, he praised the men who kept the YMCA alive after the building fiasco: “It took a long time to live down the bust, but those who had faith in the organization and a zeal for building better young men never let up for a moment. Perhaps that unhappy incident was a blessing in disguise because it taught a lesson to many a local businessman.”

The loss of such a beautiful site was especially tough: “They were all sick they couldn’t sustain it,” recalled Bev Laws, who became YMCA general secretary in Orlando in 1963 and knew some of the men involved in the misfortune.

The Orange County Association’s financial failure in the 1920s was as crushing as its pledge drive had been spectacular, but it did not put an end to the organization. The YMCA neither died nor faded away. Dedicated volunteers, committed to the organization’s mission, kept the program alive in working with local youth. The Association weathered one of the roughest periods in the city, county, and nation because of its strength of purpose and the dedication of some outstanding volunteers who were determined not to let their YMCA disappear.

This Association would emerge anew in the early 1940s, fully in the public eye, ready to make great plans once again. O’Neal observed that the enthusiasm and need for a YMCA was as great as ever in Orange County, and hinted at the ecumenical turn the organization would soon take by abandoning its early evangelical orientation. “To carry on,” he wrote in his 1932 memoirs, the YMCA “needs and must have the united support of all denominations, creeds, and faiths.” Carry on it did, although another World War would intervene before the Association solidified its presence in Central Florida. Decades would pass before the Orange County YMCA erected a building of its very own. As Laws later observed, “Usually, it’s three strikes and you’re out. They got a fourth time at bat.”

Inserts and Footnotes

EVOLUTION OF THE NATIONAL YMCA

IN THE EARLY decades of the new century, the YMCA’s work greatly expanded and changed as the United States matured Young men, many of them immigrants, few of them Protestants, and a good number mere boys, were now working in factories. The YMCA took its programs to them at their worksites. The national Association also sought new ways to involve younger men, and in 1923 restated its purpose as bringing ”young manhood and boyhood” in the US. and other lands “under the sway of [Gods} kingdom.”

One route to reaching boys was through their schools, and the YMCA expanded school-based programs vigorously from 1925 – 1930. Besides the Hi-Y Clubs for both boys and girls, a Gra-Y program for elementary school boys and Y-Indian Guides were created in the 19 20s, the latter inspired by a Native American model of father-son fellowship. By 1930, these initiatives accounted for phenomenal growth in the Association.

The Association began as a segregated organization in the US., but YMCAs for black members had originated in 1853, with a separate “Colored Association” organized in Washington, D. C. by a former slave, Anthony Bowen. In 1890, the YMCA International Committee created a “Colored Men’s Department” and its first secretary, William A. Hunton of Norfolk, was the first African American to be hired by the International Committee. In 1919, a YMCA interracial commission (later, the Southern Regional Council) was initiated in Atlanta by the founder of the YMCAs Blue Ridge Assembly in North Carolina.

Julius Rosenwald, a wealthy Chicago businessman and founder of the Sears Roebuck Company, offered $25,000 in 1910 to cities that could raise $ 15,000 to construct buddings for YMCA work with African Americans. By 1930, ”Rosenwald YMCAs” had opened in Atlanta, Baltimore, and New York’s Harlem, among 25 cities in all. By the mid-1920s, 160 YMCAs were serving African Americans, and 128 chapters at black colleges tallied 28,000 members nationwide. Although segregated YMCAs would be inconsistent with the mission of the modern organization today, they were a product of the social practices of the times. Nearly all public schools, the US. Army, and even municipal bus systems were similarly segregated.

The religious character of the YMCA was changing. Most local Associations had, in practice, already abandoned church affiliation as a requirement for membership. In 1931, the National YMCA convention formally revised its statement of purpose to eliminate the narrow theological membership test that dated to 1869. Yet even though it was more inclusive now, the Association remained resolutely Christian. Its 1931 statement identified the YMCA as “a worldwide fellowship of men and boys united by a common loyalty to Jesus Christ for the purpose of building Christian personality and a Christian society.”

Inspired by women’s suffrage, and similar changes in society at large, females were eager to join the YMCA, and many Associations courted their membership. By 1926, the increasing focus on women and girls was viewed as one of the most critical changes in the YMCA. While there was great resistance in some Associations, the more welcoming YMCAs continued to develop programs with and for women. In 1933, the National Board (as the governing body was renamed in 1924) finally voted that individual Associations could admit female members-effectively establishing local control-and the Association of Secretaries formally recognized and admitted women to YMCA staff positions.

When World War I began in Europe, well before the United States joined in, the YMCA continued the relief work it began during the Civil War. John R. Mott, general secretary of the YMCA International Committee in 1917, pledged to President Woodrow Wilson the “full service of the Association movement.” Wilson accepted Mott’s offer and the YMCA was put in charge of canteen operations, staffing them with 26,000 men and women at home and overseas. The Association also appointed a National War Work Council to campaign for contributions with six other charitable organizations. Raising a total of $200 million, the Council became the forerunner for other federated fund drives.

Relief efforts would be needed again in 1939, when war broke out in Europe. The National Council joined with the World Alliance of YMCAs to provide aid to prisoners of war. The YMCA War Work effort provided the model for the massive United Services Organization (USO), and the YMCA became one of its several sustaining organizations.

THE MAGNIFICENT 13: YMCA BOARD MEMBERS, 1935

Ward W Adair, Col. E. G. Akin, S. A. Bickford (1932-1942), O. S. Davis, C. L. Durrance (1925- 1942), Clarence M. Gay (1935-1946 and 1955-58), A. N Goodwin (1925-1942), S. Kendrick Guernsey (1935-1943), Victor Hutchins, Edwin L. Miller, John Franklin Schumann (president 1927-1941), Campbell Thornal (1935-36), A. H. Whitford.

DONALD A. CHENEY

JUDGE DONALD A. CHENEY, who held the Orange County YMCA together through its worst years, was educated at Rollins Academy and Dartmouth College. The long-serving YMCA board member also served as a Rollins trustee for many years and eventually, as assistant to its president, Hamilton Holt. His marriage to Fanny S. Robinson, daughter of Captain Benjamin Robinson, the former mayor and well-loved pioneer, produced three children.

An avid outdoorsman, Judge Cheney’s civic endeavors were many: Scouting leader, charter member of Rotary, director of the Orlando Chamber of Commerce, deacon of First Presbyterian and in 19 25, a founding member of the new Park Lake Presbyterian Church. When the Orange County Historical Commission was formed in 1957, judge Cheney became its chairman. He was instrumental in collecting and preserving data at the History Center, including much of what exists about the early YMCA.

TIMELINE

1926: Orlando population 25,000.

1927: $1 million courthouse opens, with jail on top floor.

1928: Orlando Municipal airport opens. April 1 is stock market’s greatest day ever.

1929: Panic run on banks in August.

1930: Orlando population 27,000; Orange County nearly 50,000.

1931: Daily Sentinel and Orlando Evening Reporter-Star combine.

1933: 3,400 in Orlando on relief.

1936: Martin Andersen buys Orlando Sentinel and Star.

1938: First Community Chest organized in Orlando.

1939: Drought devastates Central Florida; war declared in Europe.

1941: United States joins the World War.