TWO EARLY ATTEMPTS AT A YMCA 1885–1925

EARLY SETTLERS IN Orlando and Orange County were a plucky lot, both the white pioneers and runaway slaves from nearby southern states in the nineteenth century. This area of Florida was once the terrain of Seminole Indian tribes. Three successive wars, and federal policy that required them to go west, drastically reduced their numbers. By 1842, fewer than 300 Seminoles remained in the state, down from nearly 5,000. At the same time, the United States government was enticing white settlers to Central Florida with promises of land, hoping they would overpower and deplete the ranks of the remaining Seminoles.

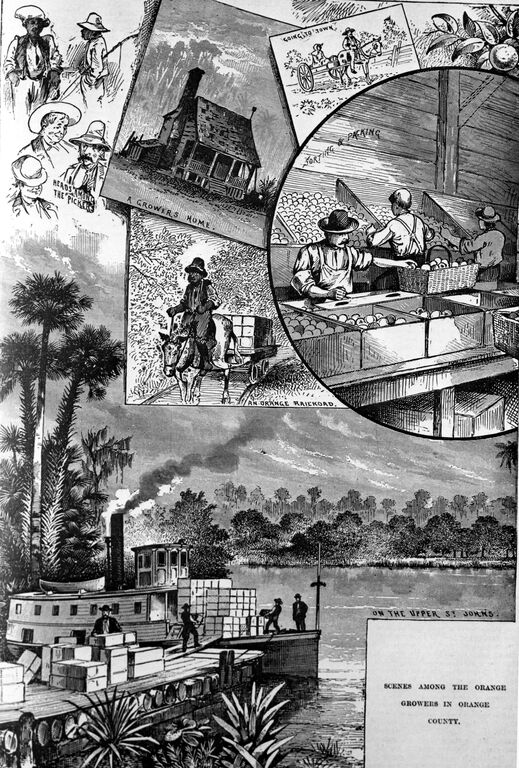

The early pioneer families built their log cabins and lean-tos on clearings of sandy soil where they cultivated fruits, vegetables, and sugar cane, and put cattle to pasture on vast brown plains. Tall pine forests offered some relief when sultry summer heat reached sweltering levels. The nearby marshlands and scrub brush that harbored rattlesnakes, alligators, and swarms of killer mosquitoes were less hospitable, and posed a continuing threat of disease and death to both livestock and human settlers.

Central Florida’s formidable frontier rewarded only the hardiest- or most desperate- of pioneers and adventurers. The town of Orlando, like others in the state, grew up around a military stockade. As Eldon H. Gore observed of the early settlers, in his 1951 history of Orlando, “These men and women took chances in coming into this Indian community and trying to establish a businessthat would make them a livelihood. Some succeeded and others lost all they invested.”

Florida achieved statehood in 1845, but the Civil War set it back considerably. The early settlers endured impoverishment and near starvation when blockades forced them to forage for food. Though it took several years, civil government was reestablished by 1868 and Orlando was incorporated as a town in 1875.

For some time, Orlando remained a rough-edged place. Cow punchers frequently met up there and ordered drinks at the city’s two saloons without even dismounting from their horses. The post-war Reconstruction Period saw ongoing cattle wars, lawless ness, and land-grabs, as drifters and gunslingers threatened Central Floridians with a breakdown in civil society. Gore offered this view of life in Orlando around 1874:

“The razorback hogs whet their backs against the steps of the wooden courthouse and slept underneath at night. The courthouse floor was covered with sawdust, so the tobacco chewers did not have to bother to spit out of the windows. The rooms were used on Sundays for religious services and the fleas were so thick no one went to sleep. These were the good old days we hear about.”

Nevertheless, settlers who survived brutal years on the Florida frontier would reap large rewards, as many of them carved out huge cattle ranches and bountiful citrus groves.

THE TURNING POINT: TRAINS ARRIVE

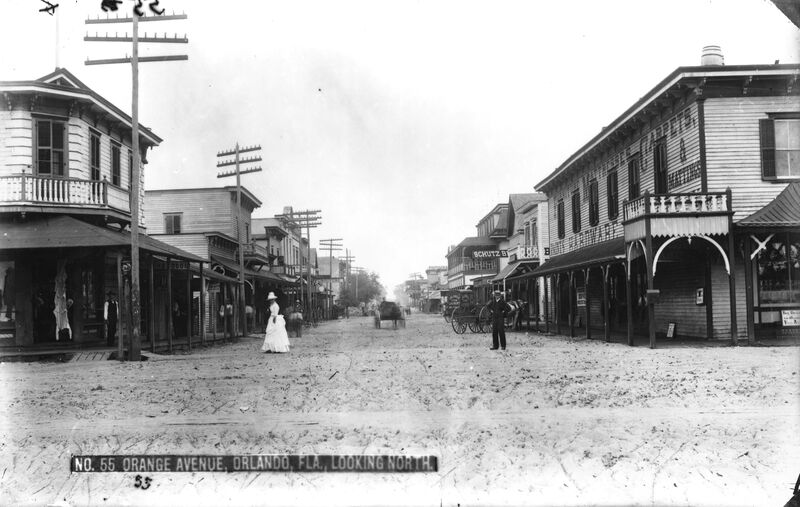

ORLANDO, THE SEAT of Orange County since 1857, was a more respectable town by 1880. Its 200 inhabitants had established four stores, a hotel, a blacksmith and wagon shop, and a livery stable. The entire business district surrounded the wooden courthouse on three sides. Its numerous lakes were lush with pines and palmetto trees, and many settlers considered the climate ideal. Thousands of cattle still roamed the surrounding woods, however, and Saturdays were known as “Cracker Day,” when country folk came to town in covered wagons, on mules, or by horseback to trade goods and enjoy spectacles like alligator wrestling.

Civilizing influences took hold as pioneers gradually introduced institutions they held dear, such as schools and churches. One homesteader, William C. Roper from Georgia, helped create a county school board in 1869. When schools opened in 1871, Roper became the first superintendent of public instruction. The Orlando Court House and the Union Free Church School were erected in 1872, the latter accommodating both pupils and worshippers. Services for Methodists, Baptists, Episcopalians, and Presbyterians were typically held there, led by traveling preachers.

Nothing, however, could rival the railroad in bringing change to Orlando. The arrival of the narrow-gauge South Florida Railroad in October 1880 touched everything and everyone. The newspaper owner, realtor, and eventual mayor Mahlon Gore observed that the rails put Orlando firmly on the map as a place “full of the most alluring opportunities for men of nerve and gumption.” Settlers poured into town from all corners-the northern and Great Plains states, the British Isles, and Europe.

As the trains discharged settlers, Orlando’s growth was truly startling. Surveyors were active everywhere, laying out land for new railroads and lumber and turpentine companies. As industries claimed turf, and trees made way for streets, open range and grass lands began to recede. By 1884 Orlando boasted 41 mercantile establishments, three livery stables, five sawmills and two lumber mills to feed the building boom. Mahlon Gore-Eldon Gore’s uncle-arranged for a census that year, which showed the city’s population at 1,666, more than eight times what it was in 1880.

Capital was accumulating in Orlando from commodity sales, particularly the plentiful citrus crops. Merchants and bankers followed, and Orlando grew flush with commerce, finance, and culture. By 1886, just two years later, the city’s population had leaped to nearly 4,000 and supported two weekly newspapers, 50 stores, five first-class hotels, two carriage shops, a machine shop, an ice fac tory, four drugstores, three bakeries, and several confectionaries and restaurants. It even had an opera house. With the area’s real estate prices rising fast, Orlando branded itself “The Phenomenal City.”

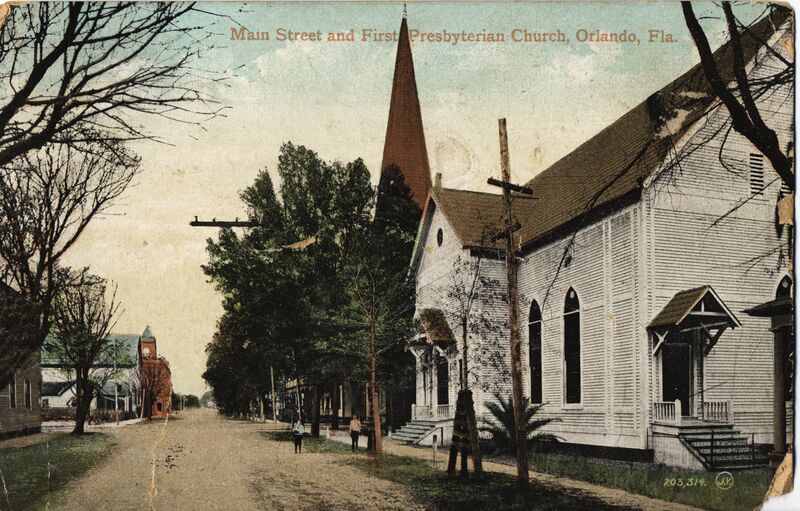

Its new citizens were changing the Phenomenal City, not only with their business ventures but with their personal values and beliefs. The town now supported seven churches and a seminary. Most of the pioneers were fervent Protestants who established their denominations and acted quickly to give them permanent homes. Orlando Baptists built a church in 1880, followed by the Methodists in 1881, and the Episcopalians in 1882. The Presbyterian congregation erected its church in 1883. The first Catholic Church opened its doors in 1885, and by 1888 the Congregational Church boasted its own house of worship as well.

Orlando’s black community claimed three houses of worship: Mount Zion Missionary Institutional Church, organized in 1880; St. John Episcopal in 1885; and Mount Olive Christian Methodist Episcopal Church in 1886. The fast-blooming frontier town now possessed all the accoutrements of a full-fledged city.

THE FIRST TRY AT A YMCA

SEVERAL NEWCOMERS WITH a can-do spirit brought another idea with them to Orlando. They hailed from states where a unique organization had taken root in mid-century and was now growing exponentially. The Young Men’s Christian Association, or YMCA, was spreading throughout the nation after surmounting daunting obstacles in its early decades. By ministering to the moral, social and spiritual needs of young men, the YMCA became a mainstay in many communities. Rapid industrialization and its opportunities were drawing multitudes of young men to American cities, and they were leaving family and trusted friends behind. The new organization was created to sustain them in these new, unfamiliar surroundings. The Association enlisted the support of evangelical Protestant churches, and local congregations typically became loyal YMCA backers. (The YMCA’s Origins)

In 1885, Frank A. Curtis arrived in Orlando from Maine, a refugee from harsh northern winters and a difficult childhood. Curtis had spent four years of his adolescence as a soldier in the Union Army. Seeking better health in Florida, he brought a youthful optimism and spirited approach to his new life in Orlando, along with a strong attachment to the Methodist Church. Curtis joined the local Methodist congregation immediately and remained an active member until his death in 1923.

To get a local YMCA going, Curtis recruited Ingram Fletcher, his partner in a fire insurance and real estate business. TI1e energetic Fletcher, also a four-year war veteran and earnest Methodist, had worked in banking in Indianapolis and would soon become the Florida State Bank’s first cashier in Orlando. On December 22, 1885, less than a year after Curtis had arrived in town, he and Fletcher called a meeting at Charles F. McQuaig’s real estate agency to organize a YMCA. They signed up 12 charter members, and by January 1886 the YMCA of Orlando was formally up and running.

William Russell O’Neal, an Ohioan who joined Curtis and Fletcher in their business in 1887, was a prolific newspaper columnist with multiple interests who would later write valuable memoirs. There he noted that Fletcher, with his wide network of acquaintances, was “always a booster … of anything that would improve or develop a higher type of citizen.” Of both men, O’Neal observed, “Curtis and Fletcher were eager to encourage others on their religious path. Both being ardent churchmen, they at once sought to organize the young men of the town into a Christian Association. They chose the YMCA as the form of organization”. As war veterans, Curtis and Fletcher took a keen interest in helping other young men in unfamiliar situations since they knew “something of the ways of young men, and the temptations sur rounding them,” O’Neal wrote. In his depiction of Orlando in this era, the town’s need for a YMCA was apparent:

“There was a saloon, or more, in every business block, with rooms above or adjoining where games of chance were openly played. Now and then the city marshal would make a raid; almost without exception those present in the rooms were engaged in reading the newspapers or playing dominoes or checkers. The usual report was that it was a perfectly proper place for young men and maidens to pass the evening.”

The two founders became officers of the fledgling YMCA, Fletcher as its first treasurer and second president and Curtis as the first recording secretary, then boys’ work secretary. The young businessmen handily recruited other up-and-comers, men of character and enterprise, who were building up Orlando’s business and civic sectors. I. M. Auld, who arrived from South Carolina in 1882, served as the Association’s first president. Co-owner of an ice fac tory, Auld was also president of the Orlando Farmer’s Alliance, a notary public, and on the staff of the Orlando Record.

YMCA vice presidents included A. W Starbird of Copeland & Starbird, contractors and builders, and Edward H. Rice, an 1882 Georgia transplant who sold fine furniture on South Orange Avenue. James LeRoy Giles served as finance committee chair. Giles, a native of Zellwood, first clerked for other merchants and then started his own general store on West Church Street with Edward Kuhl. With Albert Gallatin Branham, Giles introduced Jersey cows to Orlando in 1884, giving the area its first dairy farms and fresh milk. Giles soon became a major home builder and dealer in property. His interest in youth was well known: “The Giles home was always open to the younger set of Orlando,” Eldon Gore observed.

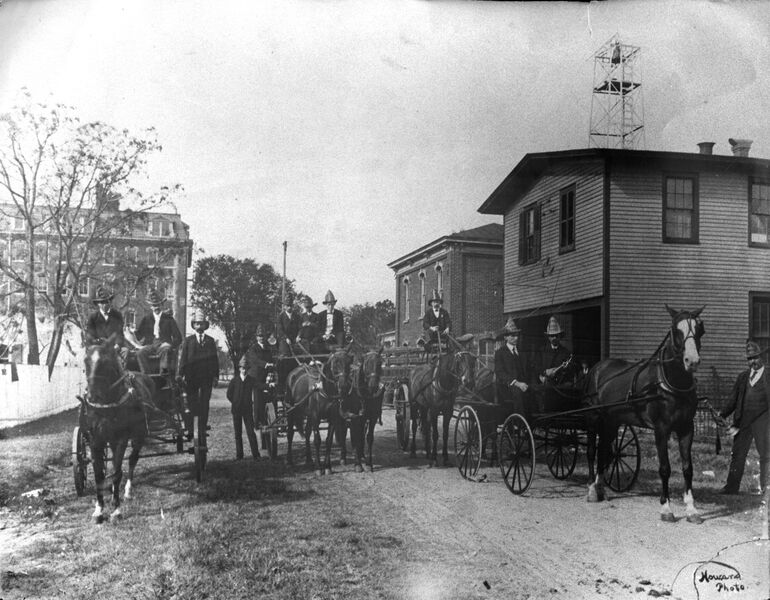

Sidney Edwin Ives followed Giles as the YMCA’s finance committee chair, and then served as vice president in 1887. Ives had arrived four years earlier from Georgia and opened a grocery on East Church Street. Virginian Milton Obadiah Dovell served on the YMCA library committee and as recording secretary in 1887; he clerked briefly in the post office and spent a decade with the South Florida Sentinel. WA. White, proprietor of one of Florida’s oldest retail establishments, chaired the YMCA reception committee; he sold dry goods, gentlemen’s apparel, and shoes in his large wooden building at Orange and West Church. Another Association member, John Wesley Gettier of Maryland, worked with the railroad for 25 years and served as Orlando’s volunteer fire chief for a decade.

Attorneys were prominent in the membership, too. Captain James D. Beggs, a 30-year-old Florida native, served on the YMCA library committee. Beggs shared a law practice with Willis Lucullus Palmer, a talented orator from Georgia. The two lawyers, both insightful politicians, were often consulted on pressing matters. Beggs had already served as city and state attorney and county court judge, while Palmer wrote many unsigned editorials in local newspapers. Both gave active support to the YMCA. Maryland native George Newell, a lawyer and charter member of the Orlando and Winter Park Railroad Company, was the Association’s treasurer and educational committee chair in 1887. The following year, he became county superintendent of registration.

However civic-minded, businesslike and devout, these were also high-spirited men. Newell could always be counted on to add a spark to social gatherings. One oft-told tale portrayed him as the camp cut-up at an 1885 outing at Lake Butler, banging on a dishpan early in the morning to arouse fellow campers. When they were slow to rise, Newell threw water between cracks in the cabin logs, emptying them out quickly. He later played Dr. Paracelsus in the operetta “The Doctor of Alcantara” at the Orlando Opera House. Another YMCA member, Judge John Moses Cheney, was in the cast. The early Orlando Association emulated its parent organization in many respects. The YMCA was created in England in 1844 by George Williams, who like Orlando’s James Giles, began as a clerk in a dry-goods establishment, in London. Williams initially gathered a dozen pious young Protestants who also held jobs in the commercial sector and led devotional exercises in rooms above the store where he worked. Soon these workers were reaching out to other young men to help them strengthen their faith in the face of often-deplorable conditions during the Industrial Revolution. Williams and his friends created the YMCA to safeguard them selves and other new arrivals against London’s abundant evil temptations. Their employers eagerly supported this new evangelical organization for young men, by young men.

FITTING UP ROOMS

IN EARLY 1886, the Orlando YMCA briefly rented space above A.H. Birnbaum’s clothing and dry goods store, on the northwest corner of Orange Avenue and Church Street, to use for devotional exercises and as a reading room. By March, the YMCA’s Monthly Bulletin announced its move to “three nicely fitted-up rooms” on the second floor of Charles E. Lartigue’s brick building, at the northeast corner of Church and Court Streets.

The reading rooms, open from 8 a.m. to 9 p.m., were well patronized. They offered more than 75 newspapers and magazines, ranging from Scientific American to publications of the Temperance Alliance. Since Orlando was officially a “dry” town, the YMCA’s water cooler was especially popular, always filled with refreshing ice water. “We are rejoiced to see the change from ‘firewater’ to ice water,” the Bulletin declared.

Apparently, the organization struggled to retain members through its first summer, but by October 1886 the Bulletin noted that “the clouds are now breaking.” By January 1887, yearly dues were increased from $1 to $2, and the board of directors from six to 10 members. “Sustaining” memberships, presumably for established citizens, cost $10.

Several church women, including Mrs. Frank Curtis and Mrs. Thomas J. Shine, formed a Ladies’ Auxiliary to help furnish the YMCA rooms. The Auxiliary claimed 69 members by October 1887. They apparently knew their place in the Association: “The distinctive work of the Ladies’ Auxiliary is that of helpers,” their report in the Bulletin avowed. “They are not to lead but to follow and be ready.”

The YMCA rooms quickly became a social and religious hub in Orlando and the site of frequent receptions. The Ladies’ Auxiliary New Year’s open house in 1887 drew 250 people and featured readings, instrumental and vocal duets, and male “quartettes.” The Bulletin described the open house as “one of the most pleasant occasions of the season.” In April, the ladies planned an “elegant programme” in the opera house.

By the following October, YMCA membership had risen to 175, more than the “well warmed and lighted and well-furnished rooms” could comfortably accommodate. “The necessity for a home was apparent,” O’Neal wrote. To the Association’s good for tune, better space was available. YMCA co-founders Curtis and Fletcher had purchased a lot on Pine and Court Streets in 1887 and put up a new, two-story red brick building with cast-iron sills for their business. Their vision also included the YMCA, and they reserved the west side of the second floor for its use. It was an excel lent location: Pine was Orlando’s first paved street. The organization soon settled in and equipped its rooms. Members enjoyed games like dominoes and checkers at the new Association Hall, and other forms of entertainment that were in keeping with Christian values. Even amusements that now seem tame, like billiards, were considered unsavory by the YMCA men, to say nothing of other enticements. As Joy Wallace Dickinson noted in her 2003 history, Orlando: City of Dreams, the place still had a “wild edge” in the 1880s and 1890s. The “vigorous” Association that Curtis and Fletcher founded helped to tame the frontier town, and “soon became one of the active religious forces in the community,” O’Neal noted.

RELIGION’S ROLE IN THE YMCA

NATIONWIDE, THE YMCA’s stated purpose was to improve the spiritual and mental condition of young men. Some local Associations added their own interpretations. The Charleston (SC) YMCA, for one, stated in 1858 that it would work toward formation and development of Christian character and activity in young men. But all YMCAs had as a commonality the evangelical basis, or ” test,” for membership.

Active membership in the Orlando Association was available to “any young man who is a member in good standing of an evangelical church,” according to the Bulletin. However, this YMCA made itself welcoming to one and all from the outset; its special aim was “the Christian education of young men, its work for and by the young men of the community.” Associate membership was open to “any young man of good moral character,” although only the evangelical, full members could vote or hold office in the Orlando YMCA. The Bulletin reported proudly that “The earnest workers of each church meet on this common ground and labor in the completest harmony, entering into every service for the cause with sectarian zeal without sectarian motives.”

A young immigrant from Wales, the Reverend J. Chris Williams, was indispensable to the early YMCA. Rev. Williams, pastor of Orlando’s Congregational Church, headed the YMCA devotional committee and brought a “Salvation Army spirit” to the organization, O’Neal observed. The pastor was appointed its secretary, as employed YMCA officers were then called, although he received no pay. He worked six days a week as a tailor to earn his living, and on Sundays he officiated at the Association’s afternoon services, in between preaching in church in the morning and sometimes have been broken, but his fidelity to the work of the YMCA and the church never was.”

The secretary didn’t wait for young men to come voluntarily to the YMCA’s prayer meetings; he sought them out in the city’s bars and brothels. Rev. Williams had experienced the rough-and-tumble coal mines of Wales and was undaunted by the fights, cuttings, and even shootings that sometimes occurred in these venues of scant virtue. His zeal for bringing young men to Christ apparently over powered any concerns he may have harbored about personal harm.

In keeping with evangelical custom, all YMCA members reached out to others. ”At our prayer and praise meetings a number of young men have found the Savior precious to their souls,” the October 1886 Bulletin declared. The Bulletin, claiming a circulation of 600, ran banners atop its pages with inspirational messages such as “Watch, Stand Fast in the Faith,” and “Let Brotherly Love Continue.

The organization held gospel services every Sabbath at 3:45 P.M. in the Association Hall, followed by an evening Bible class to which “all young men [were] cordially invited.” A young men’s prayer meeting convened on Friday evenings, while Bible training classes met on Tuesdays. The January 1887 Bulletin noted that “a number of sound conversion[s]” had resulted from these devotional meetings.

Association members also conducted religious services for incarcerated men at the local jail each Sunday afternoon. These services for inmates were “highly interesting and profitable,” the missionary committee reported, presumably seeing their profit in terms of souls brought into the fold.

Religious revivals had swept the United States in the 1870s and were often sponsored by local YMCAs. The Orlando Association hosted a series of revival meetings beginning on January 1, 1887 at the Presbyterian Church, led by a Dr. McKee of Kentucky, with all congregations in town invited to participate. The YMCA also extended an invitation to a Dr. L. W Munhall of Indianapolis, “one of the most successful revivalists in the country, “to conduct meetings in Orlando in the winter of 1888 so that “many souls may be brought to Christ.”

MOLDING YOUNG MINDS

WHILE THE ORLANDO YMCA proclaimed its purpose to be Christian education of young men, the Association also had secular improvement on its agenda. To this end it published a supplement to the Bulletin in October 1887 asking the public’s aid in “establishing in Orlando a public monument- a ‘Circulation Library.’ “This so-called “Lyceum” would be run by the YMCA and be open to the general public “for literary culture and recreation … [since] we have no public library or even an apology for one.”

The Association already possessed a “respectable nucleus” of miscellaneous contributed books and, through a member’s effort possibly Fletcher’s- had received a gift from “a gentleman of Indianapolis” of several hundred volumes. The YMCA also encouraged citizens to contribute reference works and the “wholesome literature our young men and women crave” to create the collection, so that Orlando’s children “should early acquire the habit of reading and love of books for instruction and entertainment.” Since books were costly and “few homes can possess many of them,” the Bulletin stated, the YMCA sought donations of encyclopedias and standard works of fiction, history, and biology, as well as cash contributions for its library fund. The Association was well aware that a comprehensive library would help attract more young people to its threshold. “No one thing would offer greater inducement to the stranger seeking a home among us than a successful public library,” the Bulletin continued. “If each member of our community would contribute his mite we should soon obtain a library which would be a source of pride to our people and an ornament to our town.”

SETTING LOFTY GOALS

THE ORLANDO YMCA conducted its work largely through voluntary committees, among them missionary, devotional, visitation, reception, rooms, educational, boys’ work, and membership, supplemented by the efforts of Rev. Williams, the volunteer secretary. But members soon felt the need to hire a full-time general secretary. With adequate pledges in hand to pay a salary, the Association extended a “cordial and unanimous summons call” to Porter Hardy, a 25-year-old YMCA secretary in Petersburg, VA. Hardy came highly recommended by pastors and businessmen in his city. He assumed the post in Orlando by October 1887, when the Bulletin described a Ladies’ Auxiliary reception in his honor.

Other YMCAs were concurrently in operation in Florida, some of them in close proximity to Orlando. The Association engaged in outreach beyond the city limits, keeping up with YMCAs in places like Saint Augustine, Jacksonville, Ocala, DeLand, and Apopka, the latter two also organized in 1886. By October of that year, the Apopka YMCA claimed 19 members and a reading room. Some Orlando “brothers,” including Curtis, Starbird, and Rev. Williams, formed a delegation to their “sister city,” Kissimmee, to help men there “in this great and good cause” of establishing a YMCA, according to the Bulletin.

The Orlando men clearly saw themselves as leaders in the YMCA movement, and displayed a competitive streak. When their Association was barely a year old, they were vying to host a state convention for the seven Florida Associations. “Our thriving little city is the most central for such a Convention and our people would make it very pleasant for all the delegates who could attend,” the December 1886 Bulletin affirmed.

The Association had grand plans for itself locally as well. “We want larger quarters, larger rooms and a hall for a gymnasium,” the January 1887 Bulletin announced. “In fact, we want a Y.M.C.A. building devoted exclusively to association work. Who will be the man under God who will set the ball a rolling.”

By April of that year, the Bulletin reported that the organization had “under consideration a building to be erected by a stock company and known as the Y.M.C.A. Building.” Its interest was focused on an unidentified 46-by-30 corner lot, and reportedly half the funds had been subscribed to build it. The YMCA planned to rent out two stores and four offices on the first and second floors of a proposed three-story structure, which would offer stockholders a 12 to 15 percent return on their investment. The Association would take part of the second floor and the entire third floor, “giving them plenty of room for a Ladie’s Parlor, Reading Room, Secretaries and boys Room, Cloak and Coat Room, Kitchen, bath and closets, Gymnasium and large hall,” the Bulletin declared. A subsequent Bulletin item inquired provocatively, “Who will take $500 or $1,000 stock in the projected Y.M.C.A. building.” The ladies were standing by, the publication noted, “wide awake to the interest of the Y.M.C.A. … [they] intend to be ready to do their part when we get our new building.”

A SUDDEN DISAPPEARANCE

ALTHOUGH THE ORLANDO YMCA was said to be flourishing by its second year, O’Neal later wrote that interest in the Association began to wane, and “nothing was done for some time.” Eldon Gore, uncharacteristically brief on the subject, simply reported that after 1887 the YMCA “was then given up,” with no date specified or reasons given. However, it probably persevered in some form until 1891 or 1892. Mahlon Gore’s 1891 booklet, “A Pen and Camera Sketch of Orlando, Florida,” contains an 1889 photo of the YMCA sign on the second floor of the Pine Street building.

Without Association records to indicate closure, one of the last references to its existence at this time may be gleaned from William Fremont Blackman’s History of Orange County. The author mentions that Reverend J.W. Anderson, a former devotional chairman, was YMCA president in 1890, the year in which the pastor sold 26 acres to help create the Greenwood Cemetery. O’Neal’s memoirs refer vaguely to YMCA activities in the “late eighties and early nineties.” The 1891 Orlando street directory still lists the YMCA in the Curtis block, as does the 1892 Sanborn map.

The Association evidently failed to raise enough funds to build the home it had so desired. Short of space for activities, attendance may have dropped off. Yet after such a strong start as a prominent organization in Orlando·, the YMCA’s unexplained disappearance, and the timing of its closure, remains a mystery. External factors may well have contributed to the Orlando YMCA’s demise. In 1888, a yellow-fever epidemic hit Florida. Although the deadly mosquito-borne disease largely bypassed Orlando, the widespread fear of it in town had far reaching effects. Apprehension closed down the new Orlando Board of Trade, of which O’Neal was president; the city physician panicked and fled with his family to Alabama. Dread of the disease quite possibly curtailed activities at the YMCA. O’Neal later captured the prevailing atmosphere: “The scourge of yellow fever … swept like a prairie fire all over the south. All cities used shot gun quarantine … food supplies were not easily obtained.”

The YMCA was not the only organization to find the going rough. In 1892, O’Neal and others organized an Orlando Fair Association, purchasing 80 acres and constructing a building to house future fairs. But hard times dogged their efforts and the Fair Association disbanded, unable to pay its debts. The Panic of 1893 delivered another severe blow to the community; two institutions, the First National Bank-headed by O’Neal-and Citizens Bank were forced to close. Before they could fully recover came the Great Freeze of 1894-95, wreaking unimaginable havoc on orange groves and defeating legions of growers.

O’Neal summed up the period starting with the yellow-fever pandemic as “seven long years of disasters.” From 1889 to 1895, the city lost 75 percent of its population. Recovery would take years.

The Orlando YMCA, off to such a promising start, undoubtedly reeled from the various blows and quietly faded away during that difficult time. The book collection that the Association was so eagerly accumulating apparently disappeared as well. That initiative ultimately fell to the Sorosis Club, a women’s organization formed in 1893, which initiated Orlando’s first circulating library. The Sorosis collection eventually became the basis for the city’s first public library.

Lacking official records, one can only surmise why the YMCA shut down so soon after it started. The lack of a flagship building, as a gathering place to socialize, exercise, meet, and pray, could have contributed to the Association’s early demise. The YMCA leaders may simply have been spread too thin, trying to sustain multiple business and community activities. Every civic cause, it seemed, fell on the shoulders of the same group of pioneers. In their still-small town, there may have been too many demands placed on their time and talents.

The Board of Trade, which resumed activity in the spring of 1889, called upon the energies of several YMCA stewards, including Cheney, Fletcher, O’Neal, and Palmer. Ingram Fletcher’s friend from Indianapolis, Benjamin Harrison, had recently been elected President of the United States, and appointed Fletcher as Orlando postmaster in 1890. Fletcher left his business to serve a four-year term. Willis Palmer became Orlando’s mayor from 1891 to 1893. James Giles had begun a lifetime in politics in 1886, as an alderman. O’Neal followed Fletcher as postmaster in 1898 and served a long term.

Judge John M. Cheney and O’Neal essentially ended Orlando’s one-party Democratic reign in 1895, when both ran for seats on the city council as Republicans and won. Cheney, one of Florida’s most brilliant lawyers, was also hard at work rebuilding Orlando’s defunct water company, which he would sell back to the city as a full-fledged utility in 1922. All these activities seemingly left little time for these men to devote to sustaining the YMCA. The Orlando Association would not resurface until well into the new century. When it did reorganize, in 1905, some of its earliest members once again stepped forward, eager to do what they could to help the YMCA succeed.

TURN-OF-THE-CENTURY OPTIMISM

IN THE LAST years of the 19th Century and the start of the twentieth, Orlando began to thrive anew. Its population, reduced to less than 2,500 in 1895, had once again reached 10,000 by 1900. Prosperity was slowly returning after a truly disastrous period.

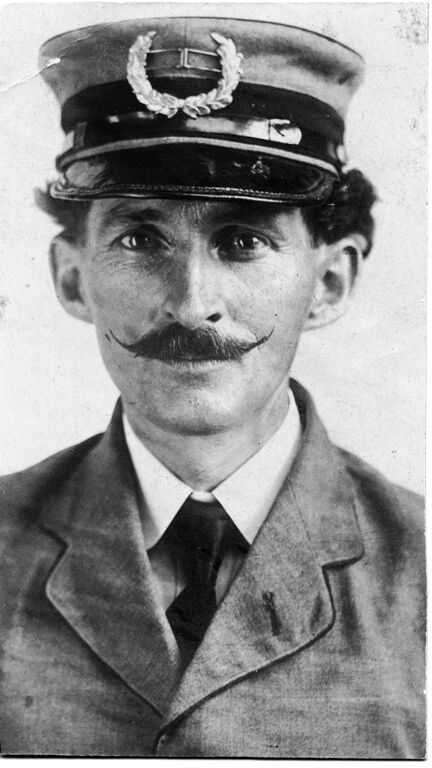

The place was still not entirely tame. Historian Eldon Gore, who arrived in Orlando from Michigan in 1903 seeking better health, was one of the city’s first mail carriers. He frequently encountered rattlesnakes, cobras, and various other varmints on his delivery route in the Lake Lucerne district. Vestiges of the frontier mentality also remained- thievery was still a problem but cattle drives were ending, and commodities now reached their markets by rail. A wonderful invention, window screens, reduced the hazard of mosquitoes, allowing citizens to sleep more comfortably in hot weather.

Temperance remained a hot button in 1900, even though the “dry” rule had been repealed. Gore wrote that the town sustained only two saloons and had an ordinance on the books against drunks. Idlers would congregate at the end of an evening by the railroad station, forcing police officers to disperse them. A “wet and dry” election in 1907 resulted in a two-vote victory for the “drys.” In short order both saloons were set afire and burned to the ground.

THE SECOND TRY FOR A YMCA

IN THIS CIVIC atmosphere of renewed optimism and moral fervor, the desire for a YMCA came to life once more in 1905, a year marked by a three-month drought in Central Florida. Businessmen and men of the cloth led the Association’s revival. Again, leading merchants, bankers, journalists, ministers, lawyers and judges all stepped forward.

Lincoln G. Starbuck, a prominent attorney and later city solicitor, called an organizing meeting at his office on April 13, 1905. Twenty-three individuals attended and signed on immediately as members; 11 others joined by proxy. The YMCA’s initial founder Frank A. Curtis was elected treasurer, and another former officer, Sidney E. Ives-merchant, alderman and elder of First Presbyterian-rejoined the Association. The newly arrived Eldon Gore joined the YMCA and became its recording secretary. Starbuck was elected vice president and Newton Yowell was chosen as president.

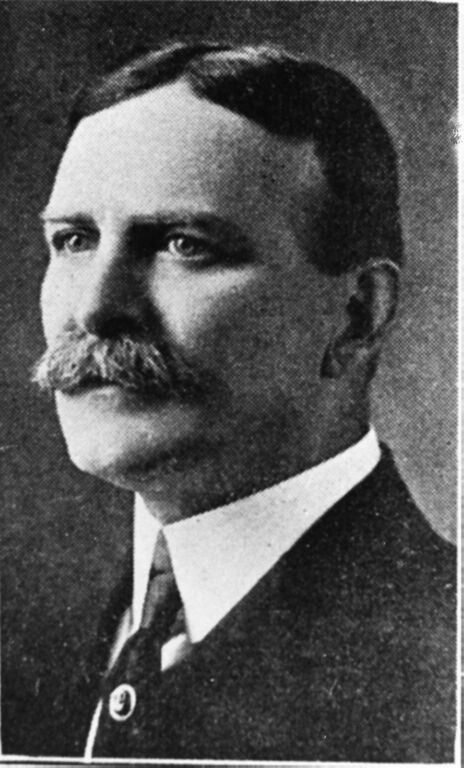

Newton Pendleton Yowell came to Orlando from Virginia with his parents in 1884. When his father died within that first year, the 14-year-old boy quit school to help support his family. He began clerking in dry goods stores, abandoning his dream of becoming a lawyer. Ten years later he opened his own establishment with his sister Hattie, a milliner, at Orange and Pine Streets-just two months before the 1894-95 Great Freeze ruined their family citrus grove. The Yowells stuck it out as other merchants failed, later moving to two floors of a larger building across Orange Avenue owned by Sidney Ives and Henry (Harry) Hill Dickson, which Yowell called the “Big White Store.”

Yowell was known for his genial manner, philanthropic spirit, and large circle of friends. Many considered him an ideal leader. A devoted churchman, he taught the Young Men’s Class at First Presbyterian Church for many years. It was one of the largest such classes in Florida, initially enrolling “boys no one else could handle,” as noted in the Orlando Rotary 75-Year History. “Yowell’s Presbyters” became an institution all its own. Historian Eve Bacon, author of Orlando: A Centennial History, noted that Yowell was “perhaps the most loved and respected man ever to live in Orlando.”

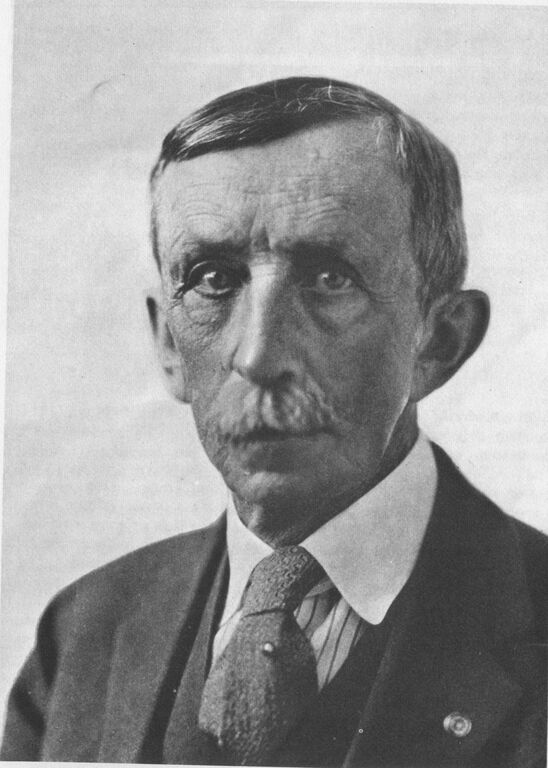

As before, the YMCA membership rolls filled with men who knew and respected one another from business dealings and church affiliations. When Newton Yowell’s brother Walter combined the Orlando Evening Star, which he founded in 1898, with the Daily Reporter and Orange County Reporter in 1906, Newton became secretary and treasurer of the Reporter-Star Publishing Company, and William O’Neal took the helm as president. As an earlier contributor to the Star, O’Neal had written news of his postal service and of Rollins College, in nearby Winter Park.

Eldon Gore worked at the Star as reporter, circulation manager, and bookkeeper before becoming a mail carrier in 1905. One of his news sources was the law firm of Beggs and Palmer, earlier sup porters of the YMCA. James Beggs was now a criminal court judge, bank president, and superintendent of the Baptist Sunday School. Willis Palmer contributed to the Star, assisting Walter Yowell in writing editorials and political news. “There was rarely a public meeting of any kind or character in the interest of city, county, or stat e, that [Palmer] was not present, diplomatic, persuasive, courteous,” O’Neal wrote. “He could be depended upon to straighten out any tangle that might arise.”

The newly reborn YMCA named a committee to find appropriate space, including merchant Eugene Duckworth, owner of the Feet Fit Shoe Store; Harry Dickson, a grain, hay, and feed purveyor from Atlanta; and Professor Fons A. Hathaway, principal of the local school. Dickson committed the YMCA Finance Committee to advancing $300 to $500 to furnish the rooms, once they were located.

Duckworth, a lifelong Methodist from Nebraska, had begun as a clerk in Yowell’s dry goods store. Dickson, an active Methodist, alderman, and chairman of the county commissioners, had partnered with Sidney Ives in 1896. They bought their two-story brick grocery store, a venture that was the forerunner of Orlando’s renowned Dickson-Ives department store.

The YMCA’s second meeting took place a week later at Beggs and Palmer’s offices on Pine Street. The Rooms Committee reported no success in securing space and recommended that the YMCA take a bold step by purchasing a lot for its own building. Former Mayor Willis Palmer, addressing the group on the value of the Association, invited them to continue using his firm’s offices until suitable space was found.

SECURING SPACE

PALMER’S OFFER WASN’T needed, however. At a mass meeting on Sunday evening, April 27, at the Methodist Church, YMCA members voted to rent three temporary rooms on the second floor of lawyer Laban J. Dollins’ building, on Pine Street near Orange Avenue, for $160 per year. Professor Hathaway, the school principal, was hired as general secretary for $25 a month to oversee the Association’s rooms. O’Neal wrote that Hathaway, “not having anything to do nights or on Saturday and Sunday,” could easily fill the post, since the YMCA rooms would only be open in the evenings and on weekends.

The Association adopted a constitution that evening, stating as its object: “to promote the interests of the young men of Orlando spiritual, intellectual, and physical.” Its leaders were guided by the constitution and by-laws of the YMCA International Committee, as the North American governing body was called. Starbuck attended to the Association ‘s incorporation as the Orlando YMCA, under the laws of Florida.

Notably, this constitution no longer contained the earlier evangelical requirement. It simply stated that “Young men of good moral character of 16 years of age and upwards may become members upon payment of dues.” An annual membership cost $6 per year, payable monthly in advance.

Religious restrictions in the YMCA were loosening nationally as well. The North American Association had a new emphasis, that of character development. Realizing that it needed to start early to be effective, the organization adopted a new motto, “Building boys is better than mending men,” and the Orlando YMCA followed suit. Boys between the ages of 12 and 16 could now use the rooms from 10 a.m. to 11 a.m. on weekdays, under the general secretary’s supervision, paying 25 cents a month in dues.

Committees for devotions, rooms, membership, gymnasium, and entertainment were formed to carry out the YMCA: s work. Devotional exercises now took place weekly. The rooms commit tee was charged with providing “reading matter consisting of daily and weekly papers and monthly magazines, keeping them in proper order.” The membership committee would “seek out and invite the young men to join the association and endeavor to enlarge the membership roll as far as possible.” The city’s ministers were also named to a special committee, to solicit more members for the YMCA.

Apparently that committee did its job; 32 new members were inscribed in the first year. Other prominent businessmen and leading citizens, such as Harry P. Leu, came aboard. At age 20 Leu began keeping the books for a boiler plant, which he eventually bought and built into one of Florida’s largest supply companies. Four Guernseys-Joseph Welburn, Frank, Charles, and S. Kendrick-were added to the YMCA rolls; Joseph and Charles became Association board members in 1906. Their father, Joseph L. Guernsey had worked in banking and then traded his grove land for Boone’s Hardware Store after the Great Freeze. His sons later sold the store to Joseph Bumby’s Hardware Company.

The membership also included Reverend L. A. Spencer, the first dean of St. Luke’s Episcopal Cathedral; Louis Dolive, of his family’s real estate and insurance firm; City Councilman R.W. Hammond; C.E. Howard, photographer, newspaper editor and longtime Methodist Sunday school superintendent; Oscar Isaacson, a builder of homes who would soon be elected to the City Council; longtime Tax Collector W.E. Martin; and mail carrier and orchestra leader G. Max Smith. Two prominent members of Orlando’s English colony also joined: Algernon Haden, a pineapple planter and polo team member, and T. Picton Warlow, a prominent lawyer, banker, county solicitor, and later, criminal court judge.

SOCIALIZING AND OYSTER STEW

MUSIC AND LITERARY events enlivened this new YMCA. Curtis, a Methodist choir member, was asked to find a suitable songbook for the Association and offered to lend his piano “on the conditions they pay the expense,” which included tuning. Five dollars “or less” was allocated to purchase music and secure an orchestra for Sunday meetings, with Starbuck, Gore, and Curtis in charge. Professor Harry Heald led the orchestra, and Frank Guernsey and a Professor Newell joined Curtis in musical numbers. The “famous Kalamazoo band,” including Guernsey, O’Neal, and William S. Branch, conspired with Dr. J.G. Litch on piano. Branch, a well-loved pharmacist from South Dakota and the organist at St. Luke’s, opened a bookstore in 1903 that eventually merged with Curtis-O’Neal, to form the O’Neal-Branch Company.

Curtis presented a list of magazines and their subscription rates for board approval, including the Literary Digest, McClure’s, Judge, Cosmopolitan, Scientific American, Everybody’s, Leslies Magazine, Red Book and Century. Orlando citizens pitched in to stock the Association library.

Women again took part in the YMCA with several, including Mrs. Eugene Duckworth and Mrs. Newton Yowell, inscribed on Association membership rolls in May 1905. They were destined once more for the Ladies Auxiliary, however, since by national edict YMCA members could only be male. Leaders of the Auxiliary were Mrs. Joseph L. Guernsey and Mrs. John M. Cheney, whose husband was now a YMCA board member, city councilman, and leader in all civic movements.

As membership grew, the Association quickly outgrew its temporary rooms in the Dollins block. In May, the YMCA got an offer that was too good to pass up. Dickson and Ives proposed to rent the Association the entire second floor of a new brick addition to their store on Orange Avenue, between Pine and Central, which housed their dry goods and gents’ furnishings establishment. The merchants would rent the space to the YMCA at $360 per year for three years, “with the privilege of five.”

Significantly, these new quarters would allow the Orlando YMCA to pursue the important physical mission of the Association in a fully equipped gymnasium. A committee consulted with an architect and builders to create an assembly hall, parlor, library, reading room, game room, bath rooms, and kitchen.

Professor William Eubert Burrell, director of physical culture and athletics at Rollins College, was hired to conduct gym classes for the Association three nights a week.

The YMCA rooms would now be open from 9:30 a.m. to 10 p.m. each weekday, and on Sundays from 3 p.m. to 9 p.m. (Games were not permitted on the Sabbath, nor would the gym be opened.) A special membership committee was appointed to “canvass thoroughly the town for new members” and report back in 30 days. In anticipation, the Association purchased 500 membership cards for future use.

Late that fall, the Orlando YMCA moved into the Dickson-Ives block. In his memoirs, O’Neal described new quarters that included “all modern conveniences of baths, reception and conference rooms such as are to be found in YMCA buildings.” The Association’s housewarming on December 14 featured a “suitable” musical program, while the public milled about marveling at the gym, library, and other rooms. A1906 news story deemed the rooms “some of the finest in the State” with “the best” furnishings-the YMCA had spent about $1,000 for everything from chandeliers to folding chairs and stoves. Telephones had recently arrived in the city, and the Association procured one through a Mr. Scott, local manager of the phone company, by paying him $9 and giving him a one-year membership in exchange for the equipment rental.

At a first anniversary praise service there, member John offered a prayer and Mrs. Benjamin M. (Marian) Robinson, the former mayor’s wife and daughter of YMCA founder Frank Curtis “rendered a solo in her usual excellent manner.” Reverend C.O. Groves of the Presbyterian Church read a scripture lesson from the 67th Psalm and spoke about “Thanksgiving.”

Rev. Groves recalled the “many good people” who had wanted to “wait and see if [the YMCA] is a go before they help to make go.” He noted that “There always has to be a warming up process and you have passed through that period and are now in a fine condition. There is not another Association in the State with such delightful quarters … now there is no reason why it cannot continue to grow and prosper.” Professor Hathaway also added his sentiments: “If only one young man is saved by the Orlando Association it is money well spent. If men do not attend in large numbers, we should not get discouraged but keep on working.”

President Yowell chimed in with his views: “Now we have this fine building that was built especially for us,” he declared. “It seems as if it was truly an opportunity of Providence to provide us with these elegant quarters.” The YMCA’s desire, Yowell added, was to double its membership of young men. The Orlando YMCA could now offer visitors and tourists, who were swelling the population significantly in winter, a member ship for $6 per year. The Association also extended an invitation to soldiers at a nearby encampment to visit its rooms during their time off. Cultivating the press, the YMCA offered membership cards to the editors of the Star and Reporter. Gore was charged with giving “the press and pulpits of the city” notices of the YMCA’s annual meeting, where oyster stew would be on the menu.

PROBLEMS LOOM

A CONFLICT SOON cropped up with Professor Hathaway. The general secretary had been unable to collect dues in August 1905, and the Association was forced to borrow $200 to cover outstanding bills. Moreover, his duties as school principal would prevent his working during the YMCA’s expanded hours. Shortly after the new quarters opened, Hathaway resigned-later to become state road superintendent-and Dr. J. G. Litch, a retired physician in Winter Park, was hired as his replacement for $50 per month. But Litch was not long for the job, either. Apparently, he liked the work so well that he left within months to enter the ministry. Finally, a Dr. Gillette, a young and popular drug clerk trained in YMCA work, became the Association ‘s general secretary.

The revived Association hosted many social and devotional meetings for members and friends. But even though new names appeared on the rolls each month, problems began to surface. Treasurer’s reports during this period reveal that income was lagging behind the bills the YMCA had accumulated. Perhaps the annual fees were too stiff to attract an adequate membership, because the officers agreed to reduce yearly dues by half in January 1906, to $3.

Personnel issues continued to plague the Association. Both Dr. Gillette and Professor Burrell resigned after about two years, when both moved away from Orlando. Possibly their paychecks were imperiled as well.

Site problems also arose in this period. The Dickson-Ives business was thriving and within two years needed to expand into its entire building. With the YMCA about to be displaced, its leaders again considered launching a building fund drive or buying quarters of their own, but they quickly grew discouraged. Suitable sites would cost $3,000 to $5,000, an outlay too steep for the Association. As O’Neal later observed in his memoirs, reflecting on that time, “We would have bought any piece of property in the business part of the city then and been well off now with the increase of price, but many thought the prices then were too high.” External problems intruded, too. Many growers in the region had suffered hardships from a major drought in 1906-1907. Trees, fruit, vegetable, and grain crops perished, livestock languished, and lakes went dry. Against those odds, the Association gave up its idea of building and, at some point in 1908, abruptly voted to dis band. The leaders sold off the furniture, paid up their indebtedness and, quite simply, quit.

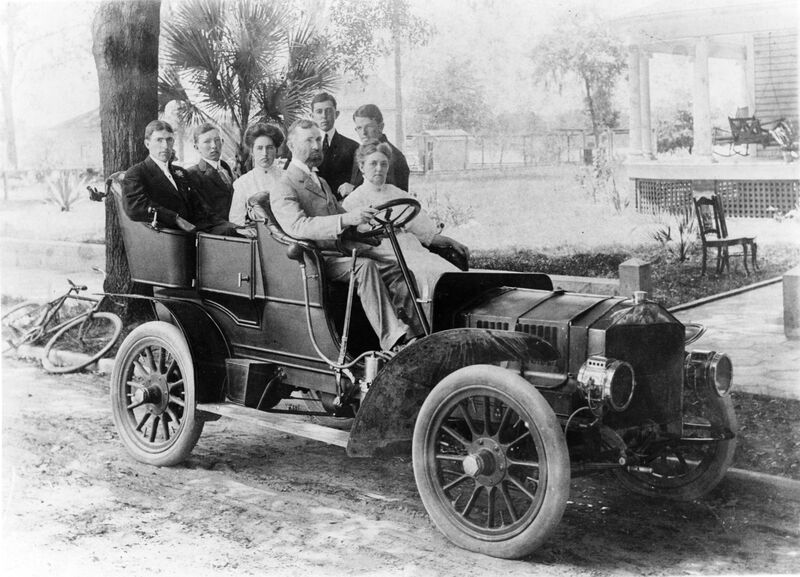

Despite the considerable enthusiasm that had brought the YMCA back to life, the interest was apparently not adequate to sustain the Orlando Association. Once again, its leaders- all leading public servants-had many other obligations in the fast-growing city and economy, now revved up by the recent introduction of automobiles.

Of O’Neal, Gore wrote: “Very few men ever lived who held as many positions in business, church, and lodge circles.” O’Neal was developing a new county fair association in 1909, for agriculture, trotting, and horse trading, with other prominent YMCA men such as Harry Dickson and James Giles. Dickson was also president of the new auto club, which undoubtedly fascinated numerous men in town, as well as the Orlando Railroad and Navigation Company.

In 1909, the Board of Trade included as members Judge Cheney, soon elected its president; Joseph L. Guernsey, vice president; O’Neal, secretary and treasurer, and later president; Dickson and Duckworth, also eventual presidents. The local Masonic Lodge counted a number of YMCA men as masters, including Cheney, Duckworth, Leu, and O’Neal, and Orlando’s new, three member school board claimed O’Neal and Yowell.

Yowell and Duckworth formed a company in 1912, bought a lot from Giles at Orange and Central, and began making plans for a four-story store, which would boast Orlando ‘s first elevator. Duckworth, who had a growing appetite for politics, would later sell his interest in Yowell-Duckworth to serve as Orlando’s mayor, from 1920 – 24. Giles, who also had political ambitions, began the first of his six terms as mayor in 1914, the year that City Solicitor Starbuck perished in a car accident. Several Association leaders opened a new city hospital, with Giles as president, O’Neal as secretary, and Yowell as a director in 1918-a year in which influenza caused 10 deaths in town. And of course, during those years the First World War claimed a significant share of young men.

The young pioneer town did not yet benefit from old money that might have been tapped to sustain the Association- as was the case in more settled cities. That would come later, as local families grew more established and prosperous. In this era, the Association leaders did not likely consider borrowing to build. Thus, after barely three years of renewed activity and much fanfare, the YMCA once again failed to take hold in Orlando, despite the involvement of stellar backers and considerable community enthusiasm.

YMCA PROGRAMS PERSIST

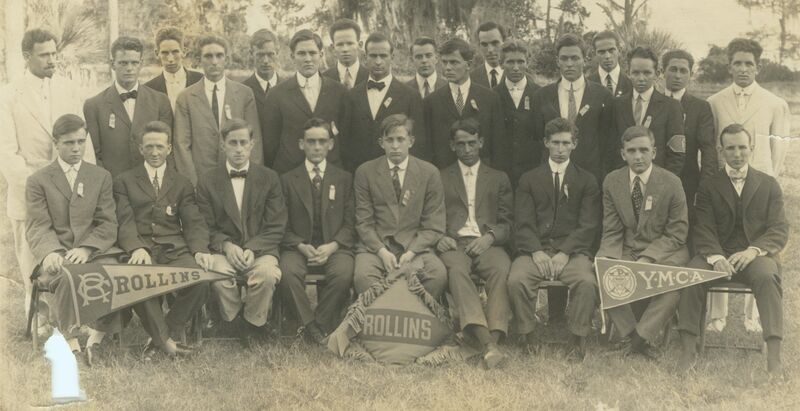

NO RECORDS OF Association activity in Orlando emerge for some time after 1908. However, the YMCA remained a force in Orange County, thanks to two other programs. In 1895, a YMCA was organized in nearby Winter Park, at Rollins College. The program fit very well with a stated goal of the College, “to provide an institution of Christian learning.”

The Intercollegiate YMCA, a national student movement, had taken shape that same year at Cornell University, led by John R. Mott and other Cornell students. Visiting YMCA secretaries quickly spread the word to other American campuses. Rollins had a visit from Fletcher S. Brockman, of the YMCA International Committee’s college department, and the Rollins Sandspur reported that students “have just begun the study of ‘Christ Among Men’ by J. R. Mott.” The Sandspur added that the YMCA “would not interfere in any way with the workings of the Christian Endeavor or Epworth League” on campus. Rather, its aim was to “to unite the college boys of both orders with a view to the systemic study of the Bible and of missions.”

The Rollins YMCA program held evening prayer meetings in Pinehurst Cottage or the College library, and on Sunday morning members met in the gym to discuss topics relating to school life. An initial membership of 10 soon doubled. Faculty records indicate that the YMCA was still active in 1899, although it would soon experience a fallow period, just as the Orlando Association did.

ROLLINS YMCA RENEWED

NO FURTHER REPORTS surface until 1906, when 25 Rollins students attend ed the first YMCA meeting of the academic year; only four of them were previous members. The meetings were still intended to help young men sustain their religious beliefs and spiritual life. That year a joint meeting in Lyman Gymnasium with Christian Education of Winter Park, on “Our Own Country, “included a stereopticon show with 50 slides “embracing views from Maine to California and Alaska.”

YMCA prayer meetings at the College considered various topics in 1908: profanity, temperance, “Christian Armor,” “Choosing a Life Work,” and “The Christian in Athletics.” Dr. William G. Blackman, the historian and then Rollins president, spoke on “Personal Purity.” His son, Worthington Blackman, then a student, spoke on “Sabbath Keeping.”

The next records of YMCA activities at Rollins are from 1913. It is tempting to speculate that the 1908 demise of the Orlando YMCA adversely affected the college program, but activity resurfaced at Rollins apparently well before the larger Association’s revival. Indeed, the Rollins program may have provided an important impetus for the eventual renewal of the countywide YMCA.

The Sandspur reported the campus YMC s reorganization on October 25, 1913 with a more rounded program than in previous years. The campus program now had an energetic leader, Raymond Wood Greene, a Rhode Island native with extensive knowledge of the Association. Greene enrolled as a student at Rollins in 1913, and simultaneously was hired as secretary to organize its YMCA. The following year the College hosted the state conference of the YMCA Intercollegiate Council, and Greene became secretary of that group as well. President Blackman, a Rollins YMCA cabinet member, opened the conference with an organ selection, playing on an Aeolian attachment.

The Rollins YMCA now aimed “to be of service to the fellows in every possible way,” according to Sandspur. In addition to its evening religious meetings, the Association also took on management of athletics and social activities for the entire student body, a d formed a YMCA orchestra. Some of its gatherings featured singing and a jazz band, while others were “union” meetings with the cam pus Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) to hear prominent speakers. The YMCA published Rollins’ all-student handbook, which contained class and athletics schedules, cheers and songs; the Association’s constitution was included in it as well.

The College Association was now grappling with broader concerns, such as social settlement work in Winter Park. A 1915 Sandspur article mentions a YMCA idea of starting a night school for “colored boys, especially caddies who have no means of learning offered in the day schools.” Outside speakers included men who had been prominent in the larger Association: N. P. Yowell, who lectured to a large group on the “value of good character and good conduct to man in his work,” and Judge T. Picton Warlow, who spoke on “The value of a good character from the Business Standpoint.” William R. O’Neal, the longtime secretary-treasurer of Rollins, brought the message that “Every man should do justly, walk uprightly and give the other fellow a square deal.”

The 1917 Tomokan yearbook noted that Rollins YMCA members “display an altruistic spirit” by arriving on campus ahead of the incoming students to meet their trains and welcome them to Rollins. Greene was now reaching out to the local community, by organizing a Winter Park Boy’s Club in 1917 for youth ages 10 – 18. “The club will be run along the lines of the YMCA plan for boys, that of developing the boy through clean and practical experiences into a good citizen and [good] Christian,” Sandspur reported.

Rollins sent the largest delegation to the Florida YMCA conference in DeLand in January 1917. There, the formation of an Association in Orlando was a topic of discussion. ”A committee was appointed to arouse public interest in the project, and it is hoped that before long Orlando will be a home of a lively YMCA,” Sandspur reported. But World War I cast a long shadow on these endeavors. As thousands of men shipped out for duty, the YMCA was deploying legions of workers for “Christian work” at European battlefronts and in U.S. military camps. The national Association recruited “1,200 of the choicest and best-trained men” for its war work. One of those recruits was Ray Greene, who took a leave from Rollins and reported to the Charleston Naval Training Camp, where he took charge of athletics for 7,000 sailors.

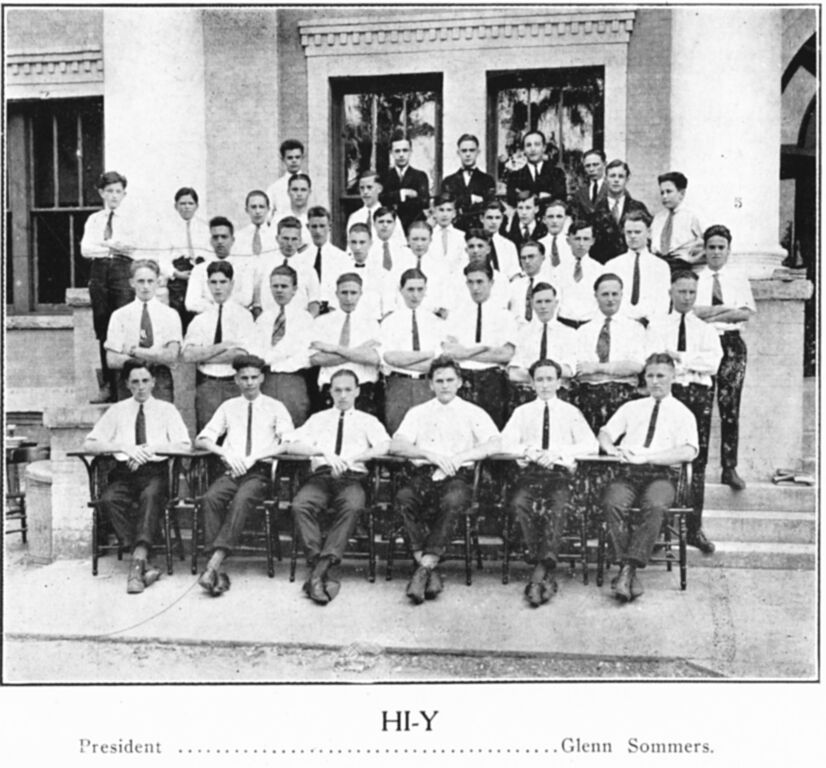

HI-Y PROGRAM BEGINS

EVEN AS THE war was draining the campus Associations, a new YMCA program was emerging in Orange County, designed for Orlando high school boys. In 1917 the national Association introduced a major new program- the Hi-Y Club-and shortly there after one began at Orlando High School (OHS). Qyite likely this local effort was helped by the committee appointed in DeLand earlier that year.

The new program grew out of Florida’s second Older Boys’ YMCA Conference held in Orlando through the efforts and “persistent energy” of one E. J. Mileham. “The county Y man,” as the OHS Echo of 1919 – 20 referred to him, Mileham was apparently dispatched to develop YMCA programs in Orange County by the Hi-Y Club s of Florida or the national Association. By this time, a county Association had apparently formed to support that effort. The names of William Edwards, as president of the Orange County YMCA, and C. R. Tidwell, as treasurer, accompanied Mileham’s on a window card.

Mileham had been a volunteer YMCA leader in his small New York hometown before joining the Rochester (NY) Association as assistant physical director. When World War I began, he went to Fort Oglethorpe, GA as Y physical director, and soon thereafter assumed the YMCA position in Orange County to organize programs for youth. Former leaders of the dormant Association surely welcomed Mileham wholeheartedly and provided assistance. YMCA loyalist Eugene Duckworth, whose son Manly was a Hi-Y member, offered “willing” guidance to the OHS Club, “though necessarily always irregular” in 1919-1920- the year he became mayor after a fierce race with another YMCA stalwart, James Giles.

Twelve initial Hi-Y members provided service to their school and heard talks on “a particular line of business and the principals involved.” The Hi-Y page in the 1919- 20 Echo noted that “The Hi-Y Club is an entirely new thing in this school, new in its field, new in its purpose … to create, maintain and extend high standards of Christian character … ” Soon, “high standards” became “the highest standards.” The members’ favorite entertainment was the “famous Rollins canoeing parties” on Winter Park lakes. On each outing someone fell in, including the “school marm,” Miss Dorothy Decker. The boys also enjoyed a swim party at Palm Springs, a Father-Son Banquet and later, joint meetings with the Girls’ Hi-Y.

In 1923, the national YMCA launched a program just for girls, the Tri-Hi-Y. Fifteen charter members joined the Senior Girls’ Hi y at OHS that year, led by Mrs. Raymond Rock, secretary of the county YWCA. Within two years, 52 members were participating in an annual Mothers’ and Daughters’ Banquet, weekly suppers, and Bible study hours. The mother of Club President Gladys Trimble conducted Bible lectures. In 1925, the OHS Girls Hi-Y merged with the newly introduced Girl Reserves Club. The new entity was created as “a step ping-stone for a much-needed Y.WC.A.,” and the Girls Hi-Y red triangle insignia was soon covered with the Reserves’ blue. In contrast, the OHS Hi-Y Club for boys continued unabated, along with the Rollins College program, keeping the YMCA flame lit in Orange County.

TOUTING THE TWO PROGRAMS

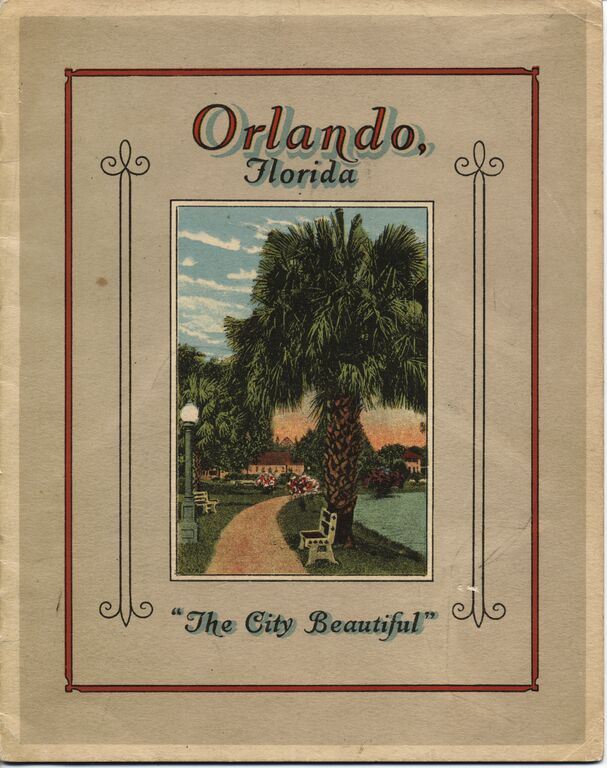

THE ROLLINS YMCA and Orange County Hi-Y programs did something that the larger Association could not: They served as showpieces for the area. In 1920, the Orlando Chamber of Commerce replaced the city’s Board of Trade, and several former YMCA men became Chamber officers, including Duckworth, Guernsey, Ives, and Yowell. In promoting Orlando, the Chamber drew on the presence of the two YMCA programs to interest new comers in “The City Beautiful.”

The Chamber’s Orlando Magazine of June 1923 high lighted attractions such as “mod ern fireproof hotels, beautiful theatres and picture houses, four teen churches,” and a “country club and eighteen-hole golf course.” Equally, the publication boasted that “Orange County has an active Y.M.C.A., with two secretaries who are doing far reaching service among the boys of the county in religious training, in character building, athletics and fitting for citizenship. Orlando is their headquarters.”

Only Mileham and the Hi-Y program, of course, were based in Orlando; the other YMCA was in Winter Park, at Rollins. General Secretary Ray Greene had returned from war service and resumed his post as Association secretary, working to reactivate the College program. The campus YMCA continued to publish the Rollins handbook, and in 1923, took on supervision and organization of the College’s “minor” athletics – basketball, tennis, track, aquatics, and baseball – quite possibly because of the YMCA cabinet’s avowed interest in “cleaner and better sports.”

The Rollins YMCA’s aims were now refocused on the spiritual, as the 1922 handbook revealed: “The making of adequate plans for the acquaintance and Christian cultivation of all men in college; special attention to the subject of Church attendance; a sufficient number of Bible study classes to reach every natural grouping of men on campus; holding of an evangelistic campaign during Holy Week; creating of an everlasting desire in the heart of every Y man to make this Y a He-man’s organization.”

By the 1924-25 academic year, most Association men, and every one of its officers, were members of evangelical churches. The campus Association had a “gospel team” of seven who con ducted services and “evangelistic deputations ” in county churches. These future ministry students stood in when pastors were ill or otherwise absent. In January 1924, the YMCA sent five men to lead Sunday services at the Apopka Presbyterian church; in March they took charge of a prayer meeting at First Presbyterian in Orlando and led church services at Kissimmee Presbyterian in May.

YMCA County Secretary E. J. Mileham gave support to the Rollins program as well as the Hi-Y. Speaking on Association his tory there in December 1923, he praised the campus branch for its work. “Th e YMCA seeks to unite men believing in Jesus Christ, and should be encouraged in all colleges,” Mileham said. ”A strong YMCA is a great inducement for students to come to any college. Rollins is bound to profit from a Y movement.”

So, would Central Florida. Mileham was working, no doubt with other loyal YMCA enthusiasts, toward that goal. The Association ‘s 1905 incorporation must have remained in force, enabling the Orange County YMCA to purchase a 40-acre camp site in 1923, where it introduced a camping program for boys. The site was on the northern side of Lake Aldrich (also known as Hickory Nut Lake) in southeast Orange County. Its seller was the Overstreet Crate Company, headed by State Senator Moses Oscar Overstreet, a YMCA member in 1906. Through these programs and efforts for local youth, the YMCA remained alive in Orange County in the teens and early ’20s, even though the formal Association was moribund, and a World War intervened. The notion that had so greatly energized Frank Curtis in 1885 and motivated Lincoln Starbuck again in 1905, and which had appealed to so many of their friends and associates, never truly disappeared. Without a strong Orlando presence, however, the organization had certainly receded in public awareness.

Inserts and Footnotes

THE YMCA’s ORIGINS

THE YOUNG MEN’S Christian Association began in England in 1844, when London newcomer George Williams invited fellow workers to gather in his room above his employer’s shop. There, they prayed to strengthen their faith and their resolve against the temptations the big city presented. These small-town shop clerks, drawn by urban opportunities, wished to keep their faith strong, maintain a safe distance from vice, and provide a moral, wholesome, social resource to like-minded young men.

Their idea was heartily endorsed by employers who saw the London YMCA as a fine tool for cultivating and maintaining an upright workforce. They helped the young YMCA men obtain rooms for reading, socializing, and devotional activities. The new Association attracted many visitors, including young American men. Back home, these men created YMCAs in Montreal, Boston, and New York City within six months in 1851 and 1852.

The North American YMCA was closely linked to the orthodox American Protestant movement. The Association required members to be of good character and to belong to evangelical churches that professed belief in Jesus based on particular Scriptures. Early YMCAs took care not to be seen as competing with churches or treading on doctrine.

The YMCA spread rapidly, taking hold in Baltimore in 1852, and a year later in Alexandria, Lexington, and Louisville. By 1856, the University of Virginia hosted a student chapter and YMCA work for Navy men started aboard a training vessel in Portsmouth. But the Civil War soon weakened both southern and northern Associations, depriving them of members who departed for battlefields. Moreover, the national YMCA movement split philosophically over the issue of slavery.

During the war, northern YMCAs created the U.S. Christian Commission to minister to all soldiers wounded and dying at the fronts. Southern Associations, including Richmond and Charleston, carried out relief work for their fighting men, against great odds-the Richmond YMCA’s property was completely destroyed

“By the close of war, the Southern Associations were virtually wiped out,” noted C. Howard Hopkins in his definitive History of the YMCA in North America; only a few maintained “some shadow of existence.” Northern YMCAs suffered as well, with just a quarter of them still functioning after the war.

The strength of the YMCA mission helped it rebound relatively soon after the war ended. The first purpose-built YMCA building opened in New York City in 1869, with a fully equipped gymnasium to support the Associations new “four-fold” purpose- spiritual, mental, social, and physical uplift. It also housed national YMCA offices.

By 1886, the YMCAs first full year in Orlando, southern Associations were rebuilding in a remarkable growth spurt: There were 203 of them at the end of that year, up from just three in 1875. Two had their own buildings, and six others were under construction. Frank B. Brantly represented the Orlando YMCA at a Southern Secretaries Conference in Chattanooga, where topics included “How can social purity be promoted among young men?” and ”How can the Secretary sufficiently interest his community in having an Association building?”

All Associations came under the YMCA International Committee, the North American governing body formed in 1879- a year when 1,770 US. and Canadian YMCAs claimed a total of 155,000 members. The Committee engaged in relief work, assisting the New Orleans and Jacksonville Associations in 1878-1879 during a yellow fever epidemic, the Charleston YMCA after an earthquake in 1886, and Raleigh and Vicksburg Ys during epidemics in 1888.

By the mid-1880s the YMCA was reaching out to young men in the workplace, at factories and through its Railroad and Army and Navy Associations. The YMCAs evangelical basis for membership, however, threatened to limit its activities and influence. Few industrial workers – many of them immigrants by the turn of the century -were Protestants; most were Roman Catholics, with Jewish men and non- believers among them as well. Typically, YMCAs allowed all men to participate, but drew the line at membership. Increasingly, however, YMCA leaders ”pragmatically rejected all theological discussion and controversy,” Hopkins noted, even if they held differing views.

National leaders like Robert Ross McBurney still saw the YMCAs mission as adherence to simple gospel and ”pressing (its) acceptance . . . upon young men.” Yet McBurney and other leaders knew that crucial support came from a strong secular force. Businessmen-merchants, bankers, and tradesmen who viewed the YMCA as a vital resource-held an enduring interest in the Association, and Hopkins noted that “Associations reflected the economic and social folkways of business groups with which they were intimately linked” An Atlanta Constitution editorial of 1885 put it more succinctly, stating that “the YMCA is the business side of religion.”

The YMCAs particular genius, allowing it to thrive even through times of radical social change, rested in refusing to narrow its focus. Instead, it became adept at adapting to community needs. Sensing that physical work provided a muscular approach to morality, YMCAs added gyms to complement religious, social and educational programs. Those innovations included the first YMCA indoor “swimming bath” in Brooklyn, NY, *in 1885, and the invention of basketball, a game using peach baskets as hoops, at the YMCAs own Springfield (MA) College in 1891. In 1906, the national YMCA launched its signature water safety and learn-to-swim campaigns.

In this era, too, Springfield College Physical Director Luther Gulick created the enduring YMCA symbol, the triangle that signifies the unity of Christian personality spirit, mind, and body.

SUBJECTS OF SABBATH MEETINGS AT THE ORLANDO YMCA

1887-1888

October 23, 1887: “Steps to a Fruitful Knowledge of Christ”

November 6, 1887: “God’s Gifts”

November 13, 1887: “Urgent Reasons for Prompt and Thorough Service”

December 11, 1887: “Christian Courage”

January 1, 1888: “The Secret of Success”

Friday Evening Meetings

November 4, 1887: “The Danger Line”

November 18, 1887: “Sowing and Reaping”

December 1, 1888: “What a Young Man Should Seek”

December 8, 1888: “Seeking the Lost”

OUR PLATFORM

“The Young Men’s Christian Associations seek to unite those young men, who, regarding Jesus Christ as their God and Savior, according to the Holy Scriptures, desire to be His disciples, in their doctrine and in their life, and to associate their efforts for the extension of His kingdom among young men.”

— YMCA Monthly Bulletin,

ORLANDO, FLORIDA, APRIL 1887.